Transfiguration of Jesus

| Events in the |

| Life of Jesus according to the canonical gospels |

|---|

|

|

Portals: |

The Transfiguration of Jesus is an event described in the New Testament, where Jesus is transfigured and becomes radiant in glory upon a mountain.[1][2] The Synoptic Gospels (Matthew 17:1–8, Mark 9:2–13, Luke 9:28–36) recount the occasion, and the Second Epistle of Peter also refers to it.

In the gospel accounts, Jesus and three of his apostles, Peter, James, and John, go to a mountain (later referred to as the Mount of Transfiguration) to pray. On the mountaintop, Jesus begins to shine with bright rays of light. Then the Old Testament figures Moses and Elijah appear and he speaks with them. Both figures had eschatological roles: they symbolize the Law and the prophets, respectively. Jesus is then called "Son" by the voice of God the Father, as in the Baptism of Jesus.[1]

Many Christian traditions, including the Eastern Orthodox, Catholic Church, Lutheran and Anglican churches, commemorate the event in the Feast of the Transfiguration, a major festival. In the original Koine Greek, the word μετεμορφώθη (metemorphōthē), "he was transformed" is used to describe the event in Luke and Mark.[3] In Greek Orthodoxy, the event is called the metamorphosis.

Significance

[edit]The transfiguration is one of the miracles of Jesus in the Gospels.[2][4][5] Thomas Aquinas considered the transfiguration "the greatest miracle", in that it complemented baptism and showed the perfection of life in Heaven.[6] The transfiguration is one of the five major milestones in the gospel narrative of the life of Jesus, the others being baptism, crucifixion, resurrection, and ascension.[7][8] In 2002, Pope John Paul II introduced the Luminous Mysteries in the rosary, which include the transfiguration.

In Christian teachings, the transfiguration is a pivotal moment, and the setting on the mountain is presented as the point where human nature meets God: the meeting place of the temporal and the eternal, with Jesus as the connecting point, acting as the bridge between heaven and earth.[9] Moreover, Christians consider the transfiguration to fulfill an Old Testament messianic prophecy that Elijah would return again after his ascension (Malachi 4:5–6). Gardner (2015, p. 218) states:

The very last of the writing prophets, Malachi, promised a return of Elijah to hold out hope for repentance before judgment (Mal. 4:5–6). ... Elijah himself would reappear in the Transfiguration. There he would appear alongside Moses as a representative of all the prophets who looked forward to the coming of the Messiah (Matt. 17:2–9; Mark 9:2–10; Luke 9:28–36). ... Christ's redemptive sacrifice was the purpose for which Elijah had ministered. ... And it was the goal about which Elijah spoke to Jesus in the Transfiguration.

New Testament accounts

[edit]

In the Synoptic Gospels, (Matthew 17:1–8, Mark 9:2–13, Luke 9:28–36), the account of the transfiguration happens towards the middle of the narrative.[10] It is a key episode and almost immediately follows another important element, the Confession of Peter: "you are the Christ" (Matthew 16:16, Mark 8:29, Luke 9:20).[1] The transfiguration narrative acts as a further revelation of the identity of Jesus as the Son of God to some of his disciples.[1][10]

In the gospels, Jesus takes Peter; James, son of Zebedee; and James' brother John the Apostle with him and goes up to a mountain, which is not named. Once on the mountain, Matthew 17:2 states that Jesus "was transfigured before them; his face shining as the sun, and his garments became white as the light." At that point the prophet Elijah representing the prophets and Moses representing the Law appear and Jesus begins to talk to them.[1] Luke states that they spoke of Jesus' exodus (εξοδον) which he was about to accomplish in Jerusalem (Lk 9:31). Luke is also specific in describing Jesus in a state of glory, with Luke 9:32 referring to "they saw His glory".[11]

Just as Elijah and Moses begin to depart from the scene, Peter begins to ask Jesus if the disciples should make three tents for him and the two prophets. This has been interpreted as Peter's attempt to keep the prophets there longer.[11] But before Peter can finish, a bright cloud appears, and a voice from the cloud states: "This is my beloved Son, with whom I am well pleased; listen to him" (Mark 9:7). The disciples then fall to the ground in fear, but Jesus approaches and touches them, telling them not to be afraid. When the disciples look up, they no longer see Elijah or Moses.[1]

When Jesus and the three apostles are walking down the mountain, Jesus tells them to not tell anyone "the things they had seen" until the "Son of Man" has risen from the dead. The apostles are described as questioning among themselves as to what Jesus meant by "risen from the dead".[12]

In addition to the principal account given in the synoptic gospels; in 2 Peter 1:16–18, the Apostle Peter describes himself as an eyewitness "of his magnificence".

Elsewhere in the New Testament, Paul the Apostle's reference in 2 Corinthians 3:18 to the "transformation of believers" via "beholding as in a mirror the glory of the Lord" became the theological basis for considering the transfiguration as the catalyst for processes which lead the faithful to the knowledge of God.[13][14]

Although Matthew 17 lists the disciple John as being present during the transfiguration, the Gospel of John has no account of it.[15][16] This has resulted in debate among scholars, some suggesting doubts about the authorship of the Gospel of John, others providing explanations for it.[15][16] One explanation (that goes back to Eusebius of Caesarea in the fourth century) is that John wrote his gospel not to overlap with the synoptic gospels, but to supplement them, and hence did not include all of their narrative.[15] Others believe that the Gospel of John does in fact allude to the transfiguration, in John 1:14.[17] This is not the only incident not present in the fourth gospel, and the institution of the Eucharist at the Last Supper is another key example, indicating that the author either was not aware of these narrative traditions, did not accept their veracity, or decided to omit them.[16] The general explanation is thus the Gospel of John was written thematically, to suit the author's theological purposes, and has a less narrative style than the synoptics.[15][16]

Theology

[edit]Importance

[edit]

Christian theology assigns a great deal of significance to the transfiguration, based on multiple elements of the narrative. In Christian teachings, the Transfiguration is a pivotal moment, and the setting on the mountain is presented as the point where human nature meets God: the meeting place for the temporal and the eternal, with Jesus as the connecting point, acting as the bridge between heaven and earth.[9]

The transfiguration not only supports the identity of Jesus as the Son of God (as in his baptism), but the statement "listen to him", identifies him as the messenger and mouth-piece of God.[18] The significance of this identification is enhanced by the presence of Elijah and Moses, for it indicates to the apostles that Jesus is the voice of God "par excellence", and instead of Moses or Elijah, representing the Law and the prophets, he should be listened to, surpassing the laws of Moses by virtue of his divinity and filial relationship with God.[18] 2 Peter 1:16–18, echoes the same message: at the Transfiguration God assigns to Jesus a special "honor and glory" and it is the turning point at which God exalts Jesus above all other powers in creation, and positions him as ruler and judge.[19]

The transfiguration also echoes the teaching by Jesus (as in Matthew 22:32) that God is not "the God of the dead, but of the living". Although Moses had died and Elijah had been taken up to heaven centuries before (as in 2 Kings 2:11), they now live in the presence of the Son of God, implying that the same return to life applies to all who face death and have faith.[20]

Historical development

[edit]

The theology of the transfiguration received the attention of the Church Fathers since the very early days. In the 2nd century, Saint Irenaeus was fascinated by the transfiguration and wrote: "the glory of God is a live human being and a truly human life is the vision of God".[21]

Origen's theology of the transfiguration influenced the patristic tradition and became a basis for theological writings by others.[22] Among other issues, given the instruction to the apostles to keep silent about what they had seen until the resurrection, Origen commented that the glorified states of the transfiguration and the resurrection must be related.[22]

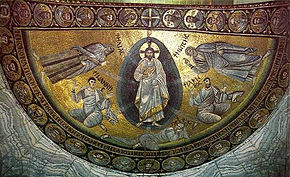

The Desert Fathers emphasized the light of the ascetic experience, and related it to the light of the Transfiguration – a theme developed further by Evagrius Ponticus in the 4th century.[22] Around the same time Saint Gregory of Nyssa and later Pseudo-Dionysius the Areopagite were developing a "theology of light" which then influenced Byzantine meditative and mystical traditions such as the Tabor light and theoria.[22] The iconography of the transfiguration continued to develop in this time period, and there is a sixth-century symbolic representation in the apse of the Basilica of Sant'Apollinare in Classe and a well known depiction at Saint Catherine's Monastery on Mount Sinai in Egypt.[23]

Byzantine Fathers often relied on highly visual metaphors in their writings, indicating that they may have been influenced by the established iconography.[24] The extensive writings of Maximus the Confessor may have been shaped by his contemplations on the katholikon at Saint Catherine's Monastery – not a unique case of a theological idea appearing in icons long before it appears in writings.[25]

In the 7th century, Saint Maximus the Confessor said that the senses of the apostles were transfigured to enable them to perceive the true glory of Christ. In the same vein, building on 2 Corinthians 3:18, by the end of the 13th century the concept of "transfiguration of the believer" had stabilized and Saint Gregory Palamas considered "true knowledge of God" to be a transfiguration of man by the Spirit of God.[26] The spiritual transfiguration of the believer then continued to remain a theme for achieving a closer union with God.[14][27]

One of the generalizations of Christian belief has been that the Eastern Church emphasizes the transfiguration while the Western Church focuses on the crucifixion – however, in practice both branches continue to attach significance to both events, although specific nuances continue to persist.[28] An example of such a nuance is the saintly signs of the Imitation of Christ. Unlike Catholic saints such as Padre Pio or Francis (who considered stigmata a sign of the imitation of Christ) Eastern Orthodox saints have never reported stigmata, but saints such as Seraphim and Silouan have reported being transfigured by an inward light of grace.[29][30]

Transfiguration and resurrection

[edit]

Origen's initial connection of the transfiguration with the resurrection continued to influence theological thought long thereafter.[22] This connection continued to develop both within the theological and iconographic dimensions – which however, often influenced each other. Between the 6th and 9th centuries the iconography of the transfiguration in the East influenced the iconography of the resurrection, at times depicting various figures standing next to a glorified Christ.[31]

This was not only a view within the Eastern Church and in the West, most commentators in the Middle Ages considered the transfiguration a preview of the glorified body of Christ following his resurrection.[32] As an example, in the 8th century, in his sermon on the transfiguration, the Benedictine monk Ambrosius Autpertus directly linked the Supper at Emmaus appearance in Luke 24:39 to the transfiguration narrative of Matthew 17:2, and stated that in both cases, Jesus "was changed to a different form, not of nature, but of glory."[32]

The concept of the transfiguration as a preview and an anticipation of the resurrection includes several theological components.[33] On one hand it cautions the disciples, and therefore the reader, that the glory of the transfiguration, and the message of Jesus, can only be understood in the context of his death and resurrection, and not simply on its own.[33][34]

When the transfiguration is considered an anticipation of the Resurrection, the presentation of a shining Jesus on the mount of transfiguration as the Son of God who should be listened to can be understood in the context of the statement by Jesus in the resurrection appearance in Matthew 28:16–20: "all authority hath been given unto me in heaven and on earth".[34]

Presence of prophets

[edit]The presence of the prophets next to Jesus and the perceptions of the disciples have been subject to theological debate. Origen was the first to comment that the presence of Moses and Elijah represented the "Law and the prophets", referring to the Torah (also called the Pentateuch) and the rest of the Hebrew Bible.[22] Martin Luther continued to see them as the Law and the Prophets respectively, and their recognition of and conversation with Jesus as a symbol of how Jesus fulfills "the law and the prophets" (Matthew 5:17–19, see also Expounding of the Law).[35]

More recently, biblical scholar Caleb Friedeman has argued that the appearance of Moses and Elijah together at the Transfiguration was because both of them had witnessed similar theophanies at Mount Sinai. Friedeman asserts that, in light of both Old Testament theophanies, the Transfiguration must be considered a theophany in which Jesus manifests his divinity.[36]

The real presence of Moses and Elijah on the mount is rejected by those churches and individuals who believe in "soul sleep" (Christian mortalism) until resurrection. Several commentators have noted that the Gospel of Matthew describes the transfiguration using the Greek word horama (Matthew 17:9), according to Thayer more often used for a supernatural "vision" than for real physical events,[a] and concluded that Moses and Elijah were not truly there.[37]

In LDS doctrine, Moses and Elijah ministered to Christ as "spirits of just men made perfect" (Doctrine and Covenants 129:1–3; see also Heb. 12:23).

Location of the mountain

[edit]

None of the accounts identify the "high mountain" of the scene by name.

Since the 3rd century, some Christians have identified Mount Tabor as the site of the transfiguration, including Origen. See[38] citing Origen's reference to Ps 89:12. Tabor has long been a place of Christian pilgrimage and is the site of the Church of the Transfiguration. In 1868, Henry Alford cast doubt on Tabor due to the possible continuing Roman use of a fortress which Antiochus the Great built on Tabor in 219 BC.[39] Others have countered that even if Tabor was fortified by Antiochus, this does not rule out a transfiguration at the summit.[40] Josephus mentions in the Jewish War that he built a wall along the top perimeter in 40 days, and does not mention any previously existing structures.[41][42]

John Lightfoot rejects Tabor as too far but "some mountain near Caesarea-Philippi".[43] The usual candidate, in this case, is Mount Panium, Paneas, or Banias, a small hill situated at the source of the Jordan, near the foot of which Caesarea Philippi was built.

William Hendriksen in his commentary on Matthew (1973) favours Mount Meron.[44]

Whittaker (1984) proposes that it was Mount Nebo, primarily on the basis that it was the location where Moses viewed the Promised Land and a parallelism in Jesus' words on descent from the mountain of transfiguration: "You will say to this mountain (i.e. of transfiguration), 'Move from here to there' (i.e. the promised land), and it will move, and nothing will be impossible for you."

France (1987) notes that Mount Hermon is closest to Caesarea Philippi, mentioned in the previous chapter of Matthew. Likewise, Meyboom (1861) identified "Djebel-Ejeik",[b] but this may be a confusion with Jabal el-Sheikh, the Arabic name for Mount Hermon.

Edward Greswell, however, writing in 1830, saw "no good reason for questioning the ancient ecclesiastical tradition, which supposes it to have been mount Tabor."[45]

An alternative explanation is to understand the Mount of Transfiguration as symbolic topography in the gospels. As Elizabeth Struthers Malbon notes, the mountain is figuratively the meeting place between God and humans.[46]

Feast and commemorations

[edit]

Various Christian denominations celebrate the Feast of the Transfiguration. The origins of the feast remain uncertain; it may have derived from the dedication of three basilicas on Mount Tabor.[23] The feast existed in various forms by the 9th century. In the Western Church, Pope Callixtus III (r. 1455–1458) made it a universal feast, celebrated on August 6, to commemorate the lifting of the siege of Belgrade[47] in July 1456.

The Syriac Orthodox, Indian Orthodox and Revised Julian calendars within the Eastern Orthodox, Roman Catholic, Old Catholic, and Anglican churches mark the Feast of the Transfiguration on August 6. In those Orthodox churches which continue to follow the Julian Calendar, August 6 in the church calendar falls on August 19 in the civil (Gregorian) calendar. Transfiguration ranks as a major feast, numbered among the twelve Great Feasts in the Byzantine rite. In all these churches, if the feast falls on a Sunday, its liturgy is not combined with the Sunday liturgy, but replaces it.

In some liturgical calendars (e.g. the Lutheran and United Methodist) the last Sunday in the Epiphany season is also devoted to this event. In the Church of Sweden and the Evangelical Lutheran Church of Finland, however, the Feast is celebrated on the seventh Sunday after Trinity (the eighth Sunday after Pentecost).

In the Roman rite, the gospel pericope of the transfiguration is read on the second Sunday of Lent – the liturgy emphasizes the role the transfiguration had in comforting the Twelve Apostles, giving them both a powerful proof of Christ's divinity and a prelude to the glory of the resurrection on Easter and the eventual salvation of his followers in view of the seeming contradiction of his crucifixion and death. The Preface for that day expounds this theme.[48]

Cultural echoes

[edit]Several church buildings commemorate the Transfiguration in their naming. Note for example the Church of the Transfiguration of the Lord in Preobrazhenskoe – the original 17th-century church there gave its name to the surrounding village (Preobrazhenskoye – "Transfiguration [village]" near Moscow) which in turn became the namesake of Russia's pre-eminent Preobrazhensky ("Transfiguration") Regiment and of other associated names.

Gallery of images

[edit]Paintings

[edit]-

Giovanni Bellini, c. 1490

-

Pietro Perugino, c. 1500

-

Cristofano Gherardi, 1555

-

Carl Bloch, c. 1865

Icons

[edit]-

Novgorod school, 15th century

-

Theophanes the Greek, 15th century

-

Icon in Yaroslavl, Russia, 1516

-

Byzantine artwork, c. 1200

Churches and monasteries

[edit]-

Transfiguration of the Divine Savior of the World celebrated in San Salvador Cathedral

-

Monumento al Divino Salvador del Mundo is an iconic landmark that represents San Salvador city. It symbolizes the Transfiguration of Jesus standing on top of earth as the savior of the world

-

Bell tower of the Eastern Orthodox monastery on Mount Tabor

-

Basilica of the Transfiguration, Mount Tabor

-

Basilica of the Transfiguration, Mount Tabor

-

The Franciscan cemetery on Mount Tabor

See also

[edit]- Acts of John, a pseudepigraphal non-canonical text that has a similar transfiguration scene (Chapter 90)

- Chronology of Jesus

- College of the Transfiguration

- Life of Jesus in the New Testament

- Son of man came to serve

References

[edit]Notes

[edit]Citations

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f Lee 2004, pp. 21–33.

- ^ a b Lockyer 1988, p. 213.

- ^ "Mark 9:2 - The Transfiguration". Bible Hub.

- ^ Clowes 1817, p. 167.

- ^ Rutter 1803, p. 450.

- ^ Healy 2003, p. 100.

- ^ Moule 1982, p. 63.

- ^ Guroian 2010, p. 28.

- ^ a b Lee 2004, p. 2.

- ^ a b Harding & Nobbs 2010, pp. 281–282.

- ^ a b Lee 2004, pp. 72–76.

- ^ Hare 1996, p. 104.

- ^ Chafer 1993, p. 86.

- ^ a b Majerník, Ponessa & Manhardt 2005, p. 121.

- ^ a b c d Andreopoulos 2005, pp. 43–44.

- ^ a b c d Carson 1991, pp. 92–94.

- ^ Lee 2004, p. 103.

- ^ a b Andreopoulos 2005, pp. 47–49.

- ^ Evans 2005, pp. 319–320.

- ^ Poe 1996, p. 166.

- ^ Louth 2003, pp. 228–234.

- ^ a b c d e f Andreopoulos 2005, pp. 60–65.

- ^ a b Baggley 2000, pp. 58–60.

- ^ Andreopoulos 2005, pp. 67–69.

- ^ Andreopoulos 2005, pp. 67–81.

- ^ Palamas 1983, p. 14.

- ^ Wiersbe 2007, p. 167.

- ^ Poe 1996, p. 177.

- ^ Brown 2012, p. 39.

- ^ Langan 1998, p. 139.

- ^ Andreopoulos 2005, pp. 161–167.

- ^ a b Thunø 2002, pp. 141–143.

- ^ a b Edwards 2002, pp. 272–274.

- ^ a b Garland 2001, pp. 182–184.

- ^ Luther 1905, p. 150.

- ^ Friedeman 2024, pp. 64–71.

- ^ Warren 2005, p. 85.

- ^ Meistermann 1912.

- ^ Alford 1863, p. 123.

- ^ van Oosterzee 1866, p. 318.

- ^ Josephus 1895, Perseus Project BJ2.20.6, ..

- ^ Josephus 1895, Perseus Project BJ4.1.8, ..

- ^ Lightfoot 1825.

- ^ Hendriksen 1973, p. 665.

- ^ Greswell 1830, p. 335.

- ^ Malbon 1986, p. 84.

- ^ Puthiadam 2003, p. 169.

- ^ Birmingham 1999, p. 188.

Sources

[edit]- Alford, Henry (1863). The New Testament for English Readers: The three first gospels. Rivingtons.

It was probably not Tabor, according to the legend; for on the top of Tabor then most likely stood a fortified town

- Andreopoulos, Andreas (2005). Metamorphosis: The Transfiguration in Byzantine Theology and Iconography. St Vladimir's Seminary Press. ISBN 978-0-88141-295-6.

- Baggley, John (2000). Festival Icons for the Christian Year. A&C Black. ISBN 978-0-264-67488-9.

- Barth, Karl (2004). Thomas Forsyth Torrance (ed.). Church Dogmatics. The Doctrine of Creation. Vol. 3, Part 2: The Creature. Bloomsbury Academic. ISBN 978-0-567-05089-2.

- Bellarmine, Robert (1902). . Sermons from the Latins. Benziger Brothers.

- Birmingham, Mary (1999). Word and Worship Workbook for Year B: For Ministry in Initiation, Preaching, Religious Education. Paulist Press. ISBN 978-0-8091-3898-2.

- Brown, David (2012). The Divine Trinity. Wipf and Stock Publishers. ISBN 978-1-61097-750-0.

- Carson, D. A. (1991). The Gospel According to John. Wm. B. Eerdmans. ISBN 978-0-85111-749-2.

- Chafer, Lewis Sperry (1993). Systematic Theology. Kregel Academic. ISBN 978-0-8254-2340-6.

- Clowes, John (1817). The Miracles of Jesus Christ: Explained According to Their Spiritual Meaning, in the Way of Question and Answer. Manchester: J. Gleave.

- Edwards, James R. (2002). The Gospel According to Mark. Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing. ISBN 978-0-85111-778-2.

- Evans, Craig A. (2005). The Bible Knowledge Background Commentary: John's Gospel, Hebrews-Revelation. David C Cook. ISBN 978-0-7814-4228-2.

- France, Richard T. (1987). The Gospel According to Matthew: An Introduction and Commentary. Inter-Varsity.

- Friedeman, Caleb T. (2024). "Moses, Elijah, and Jesus' Divine Glory (Mark 9.2–8)". New Testament Studies. 70 (1): 61–71. doi:10.1017/S0028688523000279. ISSN 0028-6885.

- Gardner, Paul D. (2015). New International Encyclopedia of Bible Characters: The Complete Who's Who in the Bible. Zondervan. ISBN 978-0-310-52950-7.

- Garland, David E. (2001). Reading Matthew: A Literary and Theological Commentary on the First Gospel. Smyth & Helwys Publishing. ISBN 978-1-57312-274-0.

- Greswell, Edward (1830). Dissertations upon the principles and arrangement of a harmony of the Gospels. p. 335.

- Guroian, Vigen (2010). The Melody of Faith: Theology in an Orthodox Key. Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing. ISBN 978-0-8028-6496-3.

- Harding, Mark; Nobbs, Alanna (2010). The Content and the Setting of the Gospel Tradition. Wm. B. Eerdmans. ISBN 978-0-8028-3318-1.

- Hare, Douglas R. A. (1996). Mark. Westminster John Knox Press. ISBN 978-0-664-25551-0.

- Healy, Nicholas M. (2003). Thomas Aquinas: Theologian of the Christian Life. Ashgate. ISBN 978-0-7546-1472-2.

- Hendriksen, William (1973). Exposition of the Gospel According to Matthew. Baker Book House. ISBN 978-0-8010-4066-5.

- Josephus, Flavius (1895). The Works of Flavius Josephus. Translated by William Whiston. Auburn and Buffalo: John E. Beardsley.

- Knecht, Friedrich Justus (1910). . A Practical Commentary on Holy Scripture. B. Herder.

- Langan, Thomas (1998). The Catholic Tradition. University of Missouri Press. ISBN 978-0-8262-1183-5.

- Lee, Dorothy (2004). Transfiguration. Bloomsbury Academic. ISBN 978-0-8264-7595-4.

- Lightfoot, John (1825). The Whole Works of the Rev. John Lightfoot: Master of Catharine Hall, Cambridge. Vol. 1. London: J.F. Dove. ISBN 9781548466398.

- Lockyer, Herbert (1988). All the Miracles of the Bible. Harper Collins. ISBN 978-0-310-28101-6.

- Louth, Andrew (2003). "Holiness and the Vision of God in the Eastern Fathers". In Stephen C. Barton (ed.). Holiness: Past and Present. A&C Black. ISBN 978-0-567-08823-9.

- Luther, Martin (1905). Luther's Church Postil Gospels: Advent, Christmas and Epiphany sermons. 1905. Lutherans in All Lands Company.

When he was transfigured on the mount, Math. 17, 3, Moses and Elijah stood by him; that means, the law and the prophets as his two witnesses, which are signs pointing to him

- Majerník, Ján; Ponessa, Joseph; Manhardt, Laurie Watson (2005). Come and See: The Synoptics: On the Gospels of Matthew, Mark, Luke. Emmaus Road Publishing. ISBN 978-1-931018-31-9.

- Malbon, Elizabeth Struthers (1986). Narrative Space and Mythic Meaning in Mark. Harper & Row. ISBN 978-0-06-254540-4.

- Meistermann, Barnabas (1912), "Transfiguration", The Catholic Encyclopedia, vol. XV, New York: Robert Appleton Company

- Moule, C. F. D. (1982). Essays in New Testament Interpretation. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-23783-3.

- Palamas, Saint Gregory (1983). John Meyendorff (ed.). The Triads. Paulist Press. ISBN 978-0-8091-2447-3.

- Poe, Harry Lee (1996). The Gospel and Its Meaning: A Theology for Evangelism and Church Growth. Zondervan. ISBN 978-0-310-20172-4.

- Puthiadam, Ignatius (2003). Christian Liturgy. Bombay: St Paul Society. ISBN 978-81-7109-585-8.

- Rutter, Henry (1803). Evangelical Harmony: Or, The History of the Life and Doctrine of Our Lord Jesus Christ, According to the Four Evangelists. London: Keating, Brown, and Keating.

- Thunø, Erik (2002). Image and Relic: Mediating the Sacred in Early Medieval Rome. L'Erma di Bretschneider. ISBN 978-88-8265-217-3.

- van Oosterzee, Johannes Jacobus (1866). Theological and Homiletical Commentary on the Gospel of Luke. Vol. 1.

The only really formidable difficulty is that adduced by De Wette, from Robinson, that, at this period, the summit of Tabor was occupied by a fortress. But even if Antiochus the Great fortified this mountain BC 219, this by no means proves that a fortress existed in the time of Christ; while if, as Josephus tells us, it was fortified against the Romans, this must certainly have happened forty years later

- Warren, Thomas S. (2005). Dead Men Talking: What Dying Teaches Us about Living. iUniverse. ISBN 978-0-595-33627-2.

The Transfiguration (Matthew 17:1–8) At first glance, this passage may seem to indicate that Moses and Elijah are alive even though Moses was ... The same Greek word, (Grk. orama), is used to describe the action in each scene...

- Whittaker, H. A. (1984). Studies in the Gospels. Cannock: Biblia.

- Wiersbe, Warren W. (2007). The Wiersbe Bible Commentary. David C Cook. ISBN 978-0-7814-4541-2.

External links

[edit]- "The Transfiguration of Our Lord", Butler's Lives of the Saints

- Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913). . Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

- Pope Benedict XVI on Transfiguration of Jesus

- The Holy Transfiguration of our Lord God and Savior Jesus Christ Orthodox icon and synaxarion