Terminal Island

Terminal Island

Isla Raza de Buena Gente Rattlesnake Island | |

|---|---|

Terminal Island. Former Gerald Desmond Bridge is visible in the right-center background. | |

| Coordinates: 33°45′25″N 118°14′53″W / 33.756963°N 118.248126°W | |

| Country | United States |

| State | California |

| County | Los Angeles |

| Cities | Los Angeles (Wilmington) and Long Beach |

| ZIP Code | 90731 |

Terminal Island, historically known as Isla Raza de Buena Gente, is a largely artificial island located in Los Angeles County, California, between the neighborhoods of Wilmington and San Pedro in the city of Los Angeles,[1] and the city of Long Beach. Terminal Island is roughly split between the Port of Los Angeles and Port of Long Beach. Land use on the island is entirely industrial and port-related except for Federal Correctional Institution, Terminal Island.

History

[edit]Before World War II

[edit]The island was originally called Isla Raza de Buena Gente[2] and later Rattlesnake Island.[3] It was renamed Terminal Island in 1891.[2]

In 1909, the newly reincorporated Southern California Edison Company decided to build a new steam station to provide reserve capacity and emergency power for the entire Edison system and to enable Edison to shut down some of its small, obsolete steam plants. The site chosen for the new plant was on a barren mudflat known as Rattlesnake Island, today's Terminal Island in the San Pedro Bay. Construction of Plant No. 1 began in 1910.

The land area of Terminal Island has been supplemented considerably from its original size. In 1909 the city of Los Angeles annexed the city of Wilmington. During this time the "Father of the Harbor" Phineas Banning,[4] held deed to roughly 18 acres of land on Rattlesnake Island.[5] Phineas Banning was instrumental in bringing innovative changes to San Pedro Bay[6] and made the first steps towards expansion. Once annexed with the city of Los Angeles the expansion was completed. In the late 1920s, Deadman's Island in the main channel of the Port of Los Angeles was dynamited and dredged away, and the resulting rubble was used to add 62 acres (0.097 sq mi) to Terminal Island's southern tip.[7]: 57

In 1930, the Ford Motor Company built a facility called Long Beach Assembly, having moved earlier operations from Downtown Los Angeles. The factory remained until 1958 when manufacturing operations were moved inland to Pico Rivera.

In 1927, a civilian facility, Allen Field, was established on Terminal Island. The Naval Reserve established a training center at the field and later took complete control, designating the field Naval Air Base San Pedro (also called Reeves Field).[7]: 60 In 1941, the Long Beach Naval Station was located adjacent to the airfield. In 1942, the Naval Reserve Training Facility was transferred, and a year later NAB San Pedro's status was downgraded to a Naval Air Station (NAS Terminal Island). Reeves Field as a Naval Air Station was disestablished in 1947, although the adjacent Long Beach Naval Station continued to use Reeves Field as an auxiliary airfield until the late 1990s.[8] A large industrial facility now covers the site of the former Naval Air Station.

Japanese American Fishing community

[edit]

Starting in 1906, a thriving Japanese American fishing community became established on Terminal Island in an area known as East San Pedro or Fish Island.[9] Because of the island's relative geographical isolation, its inhabitants developed their own culture and even their own dialect. The dialect, known as "kii-shu ben” (or "Terminal Island lingo"), was a mix of English and the dialect of Kii Province, where many residents hailed from.[10] Prior to World War II, the island was home to about 3,500 first- and second-generation Japanese Americans.[11]

Like many Japanese immigrants, the initial settlers who came to America were Dekasegi, immigrants who intended to work short time in the U.S. and then return to Japan with their built-up coffers. Many of these immigrants first arrived in Santa Monica with the hopes of creating a community there, but after their town was burned to the ground in 1916, they found their home at Terminal Island[12]. Growing fishing interests in San Pedro’s White Point and Terminal Island led many Japanese to become sought after due to their skill as fishermen, and connections to the canning industry. The first major sign of the community’s forming came in the form of the Southern California Japanese Fishermen’s Association (SCJFA), a political and social body. On January 26, 1918, their efforts were rewarded with a completed assembly hall for the community. The Hall’s grand opening saw lots of local coverage, and even a sumo mound![12]

The community saw some major political activism at the time as well, particularly combatting anti-Japanese racism. One such example was the actions of Kihei Nasu (a bilingual intellectual) that was hired by the SCJFA to write a report refuting recent attempts by Senator James D. Phelan of California that the Japanese were driving out American fishermen.[12] According to Nasu, if the Japanese were cornering the market:

If the Japanese, who are only one-third of the fishermen, are driving out American fishermen, but do not only not drive out the other foreign fishermen but are actually outnumbered two to one by them? The statement of Senator Phelan seems so illogical that it should fall of its own weight.[12]

While the report wasn’t delivered in person to Congress, it reveals the challenges the community faced and their persistence in fighting back.

The lands of Fish Harbor were owned by the City of Los Angeles, and leased out to the respective canning companies, who in turn, built workers housing. The workers’ houses were often small wooden abodes of the same make & model, that were very cramped/close-quartered.[12] The main thoroughfare was Tuna Street, which was where many local businesses were housed. The businesses themselves were so communally driven that they would look out for the interests of the community before seeking profit/competition. As noted above, fishing was integral to local ways of life, with the men being absent from family life for weeks or even months at a time. Women and young children often worked in the canneries, which was often grueling work, needing to be done as soon as the fishermen arrived with their catch.[12] For the children, schooling was the most important aspect of life, with the Kibei Nisei (roughly translating to returning Nisei)—who were sent away for education in Japan, returned with the most opportunities. Cultural infusions were becoming very popular, with the Skippers (the local baseball team) and Kendo (a martial art) being the most popular aspects of life for the youth.[12] Finally, interethnic relationships were quite strong among the Japanese and other ethnicities, particularly local white cannery owners. One such person, Wilbur F. Wood, was very often seen as very kind towards the Japanese Americans, especially realizing their strength as fishermen.[12] Tensions did brew however between local unions, but this was nothing new in American history.

On December 7, 1941, the Pearl Harbor naval base in Hawaii was attacked in a surprise air raid by the Japanese Navy, which affected the United States’ relationships with Japan and its citizens. As U.S.-Japanese relations frayed further in the late 1930s and early 1940s, nativist organizations raised new questions about the loyalty of Japanese Americans living in the country.[13] On February 19, 1942, two months after the attack, President Franklin Delano Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066. The order authorized the removal of all people deemed a threat to national security from the West Coast to one of the ten relocation camps across the nation. Immediately after Executive Order 9066 was authorized, Japanese Americans of Terminal Island were among the first groups to be forcibly removed from their homes.[14] Japanese men were the first taken into custody. They were put on trains and could not see where they were being taken, because the blinds were drawn.[12] Residents were only given 48 hours to evacuate their homes and forced to leave everything they owned behind and relocate to the detention centers. Everyone was ordered to leave Terminal Island, even if they were not Japanese, because the United States military took control of the land.[14] Terminal Island was a fishing village, located next to a United States Navy facility, which ultimately resulted in the Japanese Americans becoming fishermen. As a result of their occupation and location, they were accused of being spies for the Japanese army through the use of depth meters and fishing equipment, prior to the attack. The Justice Department and the Office of Naval Intelligence claimed that the fishermen had the ability to contact enemy vessels with their boats, radios, and equipment.[15] The FBI raided the homes of the Japanese Americans and searched for contraband which included, radios, flashlights, cameras, and morse code telegraph machines.[12] Out of the ten relocation camps, Manzanar in the Owens Valley was where most Terminal Island residents were incarcerated.

In 1945, many of the Japanese Americans who were interned began getting released. They thought that they were going back to the homes and the community they had built, however, they were completely destroyed. It was the only community where the built environment had vanished almost completely. They were given $25 and a ticket home, but they returned to nothing and were forced to relocate.[16] The Navy was responsible for razing the homes and structures of the Japanese Americans of Terminal Island.

In 1971, twenty-three Japanese Americans who were former residents of Terminal Island established a new group called the Terminal Islanders.[12] It was established in an effort to preserve the essence of their beloved community. In 2002, a memorial was established on Terminal Island by surviving second generation citizens to honor their Issei parents and preserve the memory of their Furusato, which means hometown.[14] Terminal Island is now protected under a perseveration plan established by the Los Angeles Board of Harbor Commissioners, so the struggle and history are not forgotten.

World War II and beyond

[edit]During World War II, Terminal Island was an important center for defense industries, especially shipbuilding; the first California Shipbuilding Corporation shipyard was established there in 1941.[18] It was also, therefore, one of the first places where African Americans tried to effect their integration into defense-related work on the West Coast.[19]

The San Pedro yard of Bethlehem Steel was also located on the Island. 26 destroyers were built there following the mobilization of the warship industry by the Two-Ocean Navy Act of July 1940. The yard was the third largest of the kind on the West Coast, behind the Seattle-Tacoma Shipbuilding Corporation (Todd Pacific) in Puget Sound and Bethlehem's own San Francisco yards (Union Iron Works).

In 1943, Los Angeles Shipbuilding and Dry Dock Company became Todd Pacific Shipyards, Los Angeles Division.

Also in the Port of Los Angeles (but not on the Island) was the Wilmington yard of Consolidated Steel.

In 1946, Howard Hughes moved his monstrous Spruce Goose airplane from his plant in Culver City to Terminal Island in preparation for its test flight. In its first and only flight, it took off from the island on November 2, 1947.[20]

Brotherhood Raceway Park, a 1⁄4 mile drag racing strip, opened in 1974 on former US Navy land. It operated, with many interruptions, until finally closing in 1995 to be replaced by a coal-handling facility.[21]

Preservation of vacant buildings earned the island a spot on the top 11 sites on the National Trust for Historic Preservation's 2012 Most Endangered Historic Places List.[22] In mid-2013, the Los Angeles Board of Harbor Commissioners approved a preservation plan.[23] The trust cited the site as one of ten historic sites saved in 2013.[23]

Current use

[edit]

The west half of the island is part of the San Pedro area of the city of Los Angeles, while the rest is part of the city of Long Beach. The island has a land area of 11.56 km2 (4.46 sq mi), or 2,854 acres (11.55 km2), and had a population of 1,467 at the 2000 census. [citation needed]

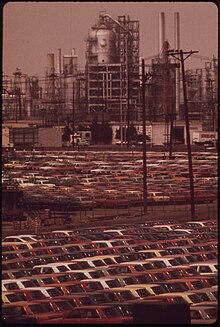

The Port of Los Angeles and the Port of Long Beach are the major landowners on the island, who in turn lease much of their land for container terminals and bulk terminals. The island also hosts canneries, shipyards, and United States Coast Guard facilities.

The Federal Correctional Institution, Terminal Island, which began operating in 1938, hosts more than 900 low security federal prisoners.

The Long Beach Naval Shipyard, decommissioned in 1997, occupied roughly half of the island. Sea Launch maintains docking facilities on the mole that was part of the naval station.

Aerospace company SpaceX is initially leasing 12.4 acres (5.0 ha) from the Port of Los Angeles on the island at Berth 240. They will refurbish five buildings and raise a tent-like structure for research, design, and manufacturing. SpaceX has been building and testing its planned Starship crewed space transportation system intended for suborbital, orbital and interplanetary flight in Texas. The new SpaceX rocket, too large to be transported for long distances overland, will be shipped to the company's launch area in Florida or Texas by sea, via the Panama Canal. The 19 acres (7.7 ha) site was used for shipbuilding from 1918, and was formerly operated by the Bethlehem Shipbuilding Corporation and then the Southwest Marine Shipyard. The location has been disused since 2005.[24][25][26]

Bridges

[edit]

Terminal Island is connected to the mainland via four bridges.[27] To the west, the distinctive green Vincent Thomas Bridge, the fourth-longest suspension bridge in California, connects it with the Los Angeles neighborhood of San Pedro. The Long Beach International Gateway, the longest cable-stayed bridge in California, connects the island with downtown Long Beach to the east. The Commodore Schuyler F. Heim Bridge joins Terminal Island with the Los Angeles neighborhood of Wilmington to the north. Adjacent to the Heim Bridge is a rail bridge called the Henry Ford Bridge, or the Badger Avenue Bridge.[27]

In media and popular culture

[edit]- Industry on Parade[28] - Continental Can Company

- a scene in Neal Stephenson's science fiction novel Snow Crash (1992)

- Visiting... with Huell Howser Episode 422[29] - The Tri-Union Cannery

- The Terror: Infamy[30][31]

- The Fast and the Furious

- Need for Speed[32]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "Map". Wilmington Neighborhood Council. Retrieved September 11, 2020.

- ^ a b Laura Pulido; Laura Barraclough; Wendy Cheng (March 24, 2012). A People's Guide to Los Angeles. University of California Press. p. 250. ISBN 978-0-520-95334-5. Retrieved August 16, 2012.

- ^ Gerrie Schipske (October 31, 2011). Early Long Beach. Arcadia Publishing. p. 93. ISBN 978-0-7385-7577-3. Retrieved August 16, 2012.

- ^ "Los Angeles Harbor Communities | History | Port of Los Angeles". www.portoflosangeles.org. Retrieved September 11, 2020.

- ^ "Water and Power Associates". waterandpower.org. Retrieved September 11, 2020.

- ^ "Port of Los Angeles Virtual History Tour | Port History". www.laporthistory.org. Retrieved September 11, 2020.

- ^ a b White, Michael D. (February 13, 2008). The Port of Los Angeles. Arcadia Publishing. pp. 57–60. ISBN 978-0-7385-5609-3. Retrieved August 16, 2012.

- ^ Denger, Mark. "Historic California Posts: Naval Air Station, Terminal Island". Retrieved August 16, 2012.

- ^ Morrison, Patt (December 7, 2021), "Before Pearl Harbor, L.A. was home to thriving Japanese communities. Here's what they were like", The Los Angeles Times

- ^ "Preserving California's Japantowns - Terminal Island". www.californiajapantowns.org. Retrieved October 12, 2020.

- ^ Kashima, Tetsuden (1997). Personal Justice Denied: Report of the Commission on Wartime Relocation and Internment of Civilians. University of Washington Press. p. 108. ISBN 978-0-295-97558-0. Retrieved August 16, 2012.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Knatz, Geraldine; Hirahara, Naomi (2015). Terminal Island: Lost Communities of Los Angeles Harbor. Los Angeles, CA: Angel City Press. pp. 150, 155–156, 164–165, 165, 171–174, 192–194, 209–212, 226–227, 255, 253, 271. ISBN 978-1-62640-018-4.

- ^ Griffith, Sarah M. (2018). The Fight For Asian American Civil Rights: Liberal Protestant Activism, 1900-1950. Champaign: University of Illinois Press. p. 104.

- ^ a b c "Japanese Memorial Terminal Island". SanPedro.com - San Pedro, California. Retrieved November 21, 2024.

- ^ "Terminal Island, California". Densho Encyclopedia. September 10, 2024. Retrieved November 21, 2024.

- ^ "Terminal Island: A Lost Tale of World War II | PearlHarbor.org". pearlharbor.org. Retrieved November 21, 2024.

- ^ "Terminal Island Memorial Monument | Japanese-City.com". www.japanese-city.com.

- ^ "California Shipbuilding Corporation (CalShip) Collection". oac.cdlib.org.

- ^ Sides, Josh (June 12, 2006). L.A. City Limits: African American Los Angeles from the Great Depression to the Present. University of California Press. p. 64. ISBN 978-0-520-24830-4. Retrieved August 16, 2012.

- ^ Porter, Darwin (March 30, 2005). Howard Hughes: Hell's Angel. Blood Moon Productions, Ltd. pp. 710–11. ISBN 978-0-9748118-1-9. Retrieved August 16, 2012.

- ^ McLellan, Dennis (May 25, 2012). "'Big Willie' Robinson dies at 69; L.A. drag race organizer". Los Angeles Times.

- ^ "LA Port Plan Makes Terminal Island Preservation a Key Goal". National Trust for Historic Preservation. Retrieved January 19, 2014.

- ^ a b staff (January 5, 2014). "A look at 10 historic sites save, 10 lost in 2013". Associated Press as reported by the Post Crescent. p. F3.

- ^ Samantha Masunaga (April 19, 2018). "SpaceX gets approval to develop its BFR rocket and spaceship at Port of Los Angeles". Los Angeles Times.

- ^ Berger, Eric (March 19, 2018). "SpaceX indicates it will manufacture the BFR rocket in Los Angeles". Ars Technica. Retrieved February 21, 2020.

- ^ Masunaga, Samantha (February 20, 2020). "SpaceX wants to build its Mars Starship at Port of L.A. — again". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved February 21, 2020.

- ^ a b Daniel Z. Sui (June 19, 2008). Geospatial Technologies and Homeland Security: Research Frontiers and Future Challenges. Springer. p. 42. ISBN 978-1-4020-8339-6. Retrieved August 16, 2012.

- ^ "" INDUSTRY ON PARADE " MAKING TIN CANS, CHICKENS, STOCKINGS, AND HOTEL RESERVATIONS 97514a". National Association of Manufacturers. June 29, 2023.

- ^ "Cannery – Visiting (422) – Huell Howser Archives at Chapman University". December 7, 2016.

- ^ Debnath, Neela (August 12, 2019). "The Terror Infamy location: Where is it filmed? Where's it set?". Daily Express. Retrieved August 21, 2019.

- ^ "New season of 'The Terror' brings horror of Japanese American internment to life". NBC News. Retrieved August 22, 2019.

- ^ "Richard Cook - Krop Creative Database". www.krop.com. Retrieved May 30, 2024.

Further reading

[edit]- Hirahara, Naomi (2014). Terminal Island: Lost Communities of Los Angeles Harbor. Santa Monica, Calif.: Angel City Press. ISBN 9781626400184.

- Regan, Lucile Cattermole (2006). The Red Lacquer Bridge. Bloomington, Ind.: AuthorHouse. ISBN 9781425983277.