Hopscotch (Cortázar novel)

This article's plot summary may be too long or excessively detailed. (January 2023) |

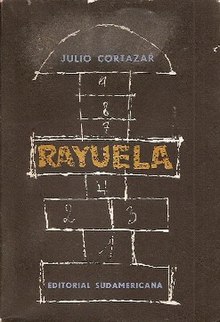

First edition | |

| Author | Julio Cortázar |

|---|---|

| Original title | Rayuela |

| Translator | Gregory Rabassa |

| Language | Spanish |

| Publisher | Pantheon (US) |

Publication date | 28 June 1963 |

| Publication place | Argentina |

Published in English | 1966 |

| Media type | Print (paperback) |

| Pages | 576 |

| OCLC | 14412231 |

| 863 19 | |

| LC Class | PQ7797.C7145 R313 1987 |

Hopscotch (Spanish: Rayuela) is a novel by Argentine writer Julio Cortázar. Written in Paris, it was published in Spanish in 1963 and in English in 1966. For the first U.S. edition, translator Gregory Rabassa split the inaugural National Book Award in the translation category.[1]

Hopscotch is a stream-of-consciousness[2] novel which can be read according to two different sequences of chapters. This novel is often referred to as a counter-novel, as it was by Cortázar himself. It meant an exploration with multiple endings, a neverending search through unanswerable questions.[3]

"Table of Instructions" and structure

[edit]An author's note suggests that the book would best be read in one of two possible ways: either progressively from chapters 1 to 56, with all subsequent "expendable chapters" being excluded, or by "hopscotching" through the entire set of 155 chapters according to a "Table of Instructions" designated by the author. Chapter 55 is left out all together in this second method, and the book would end with a recursive loop, as the reader is potentially left to "hopscotch" back and forth between chapters 58 and 131 infinitely.[4] Cortázar also leaves the reader the option of choosing a unique path through the narrative.

Several narrative techniques are employed throughout the book, and frequently overlap, including first person, third person, and a kind of stream-of-consciousness. Traditional spelling and grammatical rules are not always applied.

Plot (chapters 1–36)

[edit]The first 36 chapters of the novel in numerical order are grouped under the heading "From the Other Side." They provide an account of Horacio Oliveira's life in Paris in the 1950s. La Maga and a band of bohemian intellectuals who call themselves the Serpent Club are other characters who appear in these chapters.

The story opens with Horacio searching the bridges of Paris for his lover, a Uruguayan woman named Lucia (better known throughout the novel as la Maga), who has disappeared.

Both meet frequently with their mutual friends, the members of a group nicknamed the Serpent Club. This is a circle of artists, writers, and musicians that drink and listen to music while discussing art, literature, philosophy, architecture, and other subjects. In their discussions, they frequently mention a writer by the name of Morelli, who insists on the necessity of breaking with the linguistic forms of the moment. The group jumps from one topic to another with relative ease, but la Maga, who is not as well-read as the others, generally needs the others to explain the subjects at hand. Her vivacity distances her from the group, foreshadowing her eventual separation from it. The club, however, shows affection toward Lucia, but almost always in a condescending manner.

Horacio and la Maga had been living together for some time at the beginning of the narrative, but Rocamadour, the baby of la Maga who is in the care of a nanny in the countryside, becomes ill. La Maga has to bring him to live with her and Horacio. Rocamadour's health is too delicate to improve in the cold and cramped apartment, but la Maga is terrified by the idea of sending him to a hospital. This leads the infant to become gravely ill. Meanwhile, Oliveira increasingly resents the situation, because he had not agreed to live with a baby. During a fight, Horacio tells la Maga that she can consider their relationship to be over. La Maga bursts into tears. Oliveira leaves the apartment, possibly with the intention of visiting Pola, a lover of his. He is unsure whether he will return or not.

Later, while wandering the streets without any fixed destination, Oliveira witnesses a car running over an older man. Another witness states that the victim is a writer who lives near the site of the accident. An ambulance arrives to pick up the injured man.

A light rain begins. Horacio continues his melancholic preponderances. He is left struck by the mechanical way in which the paramedics treated the victim. To take cover from the poor weather, he steps into the entrance of a theater and decides to stay and watch the piano concert being given there by a madame Berthe Trepat.

In the theater, Oliveira listens to the compositions of Trepat, which he judges to be badly written and played even worse. The rest of the audience leaves in the middle of the concert. Everything indicates that Oliveira sympathizes with the woman, whose failure contrasts with her proud attitude. He offers to walk her home. In the rain, she tells him about her problems with Valentin, her partner, who she expects to be at home with one of his lovers. When they arrive, Horacio offers to find her a hotel, and she slaps him, suspecting he has unwholesome intentions. Oliveira walks away crying, humiliated.

He returns to la Maga's apartment, where he runs into a suitor of hers, Gregorovius. Horacio believes the two slept together while he was out. In reality, la Maga had rejected his advances. Horacio sits down with the two to have a chat in the style of the Club de la Serpiente, but they are constantly interrupted by an older man who lives on the upper floor and continually hits the floor of his apartment. At a critical point in the conversation, Oliveira touches Rocamadour and realizes that the baby is dead.

After reflecting on the senselessness of the death and considering the confusion that the event would cause, Oliveira, with his habitual attitude, decides not to communicate the terrible news. However, given the insistence of the neighbor from the upper floor, he suggests that la Maga go upstairs and confront the man. While she leaves to do that, Oliveira relates Rocamadour's death to Gregorovius. Both sit down to consider the legal implications. Gregorovius does not mention the matter when la Maga returns.

Various friends from the Club de la Serpiente arrive at the apartment. Two of them, Ronald and Babs, tell the others that one of the Club's members, Guy Monod, had attempted suicide. Later, a third member of the group, Etienne, arrives to tell them that Monod would survive but was in critical condition. The group embarks on one of their characteristic philosophical discussions, during which they discreetly communicate to each other about the horrible event that had come to pass in the apartment. La Maga is excluded from the conversation, but she finally realizes that her son has died when she tries to give him a dose of his medicine. She becomes hysterical, and the chaos that Oliveira had feared breaks loose. La Maga goes to Horacio for support, but he either cannot or does not want to comfort her, so he remains silent and decides to leave the apartment.

Later, a wake is held for the baby. All of the members attend, except Horacio, who is once again wandering the streets of Paris without a destination. When he finally returns to the apartment, various days have passed and la Maga has disappeared. Gregorovius, who is now living in the apartment, implies that la Maga may have returned to her native Montevideo, but Horacio doubts that she has the means to afford the trip. He feigns disinterest, but he suspects that la Maga may have committed suicide after the wake. Another possibility is that she had gone to stay with Pola (who had been diagnosed with breast cancer).

While walking along the bank of the Seine, Horacio runs into an indigent person who he and la Maga had met before, though Horacio does not recall the specific details. Having nowhere to go, Horacio decides to sit and talk with the beggar for a time. Her name, Horacio remembers, is Emmanuele. He accepts the woman's request to buy wine and drink together. Both end up intoxicated below a bridge. Emmanuele attempts to give Horacio oral sex, but the police arrive and arrest them.

They are taken to the police station along with two pederasts. During the journey, Oliveira continues to reflect on his search for unity and his relationship with la Maga. The pederasts, meanwhile, argue about a kaleidoscope. They note that the "beautiful patterns" inside are only visible when the lighting is correct.

The first part of the book ends with Oliveira's intuition that heaven is not a place above the Earth, but on the surface of it. However, people tend to approach it in a similar manner to the way children play hopscotch.[5]

Plot (chapters 37–56)

[edit]Chapters 37 to 56 are collected under the heading "From this Side", and the action takes place in Argentina. It opens with a brief introduction to the life of Manolo Traveler, Horacio Oliveira's friend from childhood, who lives in Buenos Aires with his wife Talita. Although Traveler is restless, the marriage appears to be on solid ground until Gekrepten, Horacio's old Argentinian lover, informs him that Horacio is due to arrive by boat. The news fills Traveler with a dark sense of foreboding; nonetheless, he and Talita greet Horacio at the docks, where Oliveira momentarily mistakes Talita for La Maga. Horacio then settles with Gekrepten in a hotel room located directly across the street from the flat Traveler and Talita share, where his mind slowly begins to unravel.

Traveler and Talita work for a circus, and when Horacio's temporary employment falls through, Traveler arranges for his old friend to be hired on there as well, though not without misgivings. Oliveira's presence has begun to disturb him, but he is unable to determine why. He wishes to ascribe it to Horacio's flirtations with Talita, but cannot do so, as there seems to be something more going on. And anyway, he has no doubts about his wife's remaining faithful to him. Unable to decipher the mystery, and unable to tell Horacio to leave them alone, he begins to sleep less and less, and his sense of restlessness increases.

Horacio, meanwhile, observing the relationship between Traveler and Talita, who more and more reminds him of La Maga, endeavors to enter more intimately into their lives, but he is unable to do so. His frustrations increase, and he begins to show signs of impending mental breakdown. One hot afternoon, he spends hours on the floor trying to straighten nails, although he has no particular use in mind for them. He then convinces Traveler and Talita to help him build a makeshift bridge between the windows of the two buildings over which Talita can cross. Traveler indulges his friend's eccentric behavior, but Talita is frightened and must be prodded into participating. She feels it is a test of some sort. In the end, Talita does not cross between the buildings.

Soon after this incident, the owner of the circus sells the operation to a Brazilian businessman and invests in a local mental institution. Traveler, Talita and Horacio decide to go to work there despite the irony of the situation, or perhaps because of it. Horacio jests that the patients in the hospital will be no more mad than the three of them, anyway. On the day the ownership of the hospital is to be transferred, they are told that all the inmates must agree to the deal by signing a document, and that the three of them must act as witnesses. They meet a good-natured orderly named Remorino as well as a Dr. Ovejero, who manages the facility. The former owner of the circus and his wife, Cuca, are also present. One by one the inmates are led in to sign the document, a procedure that lasts well into the night.

Talita becomes the resident pharmacist at the hospital, while Horacio and Traveler act as either orderlies or guards at night. The place is dark and eerie in the long hours before dawn, with the three often seeking refuge in alcohol and conversation in the pharmacy's warmer atmosphere. Remorino shows Horacio and Traveler the basement, where dead bodies are kept and cold beer can be had.

One night Horacio is smoking in his room when he sees Talita crossing the moonlit garden below, apparently heading to bed. A moment later, he thinks he sees La Maga appear and begin a game of hopscotch in the same general area; but when she looks up at him, he realizes it is Talita, who had turned and recrossed the garden. A kind of guilt, fed in part by the institution's gloomy atmosphere, begins to steal into his musings, and it is not long before he conceives of the idea of someone's trying to murder him while he is on duty—perhaps Traveler.

Later in the night, while Oliveira is on the second floor pondering over the symbolic implications of the mental institution's elevator, Talita approaches and the two talk about holes, passages, pits, and La Maga, and as they do, the elevator comes to life, ascending from the basement. One of the mental patients is inside. After sending the man back to his room, Horacio and Talita decide to go down, ostensibly to see what he was up to.

Alone with Talita and the dead bodies, Horacio finds himself talking to her not as if she reminded him of La Maga, but as if she were La Maga. In a final moment of desperation, he attempts to kiss this Talita/La Maga mixture, but is repelled. Returning to her room, Talita tells Traveler about it, who surmises that something may be seriously wrong with his friend.

Meanwhile, having retreated to his own room, Horacio is now convinced that Traveler is coming to kill him. He begins to construct a kind of defense line in the dark room that is intended to confuse and irritate an attack, rather than deter it: water-filled basins placed on the floor, for example, as well as threads tied to heavy objects (which are in turn tied to the doorknob).

Horacio then sits in the dark on the opposite side of the room, near the window, waiting to see what will happen. The hours pass slowly and painfully, but finally Traveler does try to come in, and the tumult that results brings Dr. Ovejero and the others out into the garden, where they find Oliveira leaning out the window of his room as if intending to let himself fall. Traveler tries to talk Horacio out of doing what he, for his part, insists he doesn't intend to do, though at the conclusion of this part of the book, he suddenly muses that maybe he does mean to do such a thing after all, that maybe it is for the best, and the end of the passage is wholly open to this interpretation. Only by proceeding to read the "Expendable Chapters" will the reader be able to place Horacio firmly back inside the mental institution, where, after being sedated by Ovejero, he succumbs to a lengthy delirium.

The "Expendable Chapters"

[edit]The third section of the book, under the heading "From Diverse Sides", does not need to be read in order to understand the plot, but it does contain solutions to certain puzzles that arise during the perusal of the first two parts. For example, the reader finds out a great deal more about the mysterious Morelli, as well as finding out how La Maga and Emmanuele first became acquainted. Through Morelli's writings, Cortazar hints at some of the motives behind the actual construction of Hopscotch (such as a desire to write a work in which the reader is a true co-conspirator). The inner workings of Horacio Oliveira himself are described in a much less evasive manner than in any previous chapters, as well. The section, and the book, ends with Horacio visiting Morelli in the hospital, who asks him to go to his apartment and organize his notebooks while he is away. Most of these notebooks are unpublished and Oliveira not only considers doing this work as a great honor to himself personally, but also as perhaps the best chance yet of his attaining the ninth square in his lifelong game of spiritual, emotional, and metaphysical hopscotch.

Characters

[edit]The main character, Horacio Oliveira, is a well-read and loquacious bohemian. He enjoys a mostly intellectual participation in life, as is characterized by his general passivity towards his environment, and appears to be obsessed with attaining what is referred to as a unifying conception of life, or center in which he can contentedly exist.

"La Maga" (a nickname, as her real name is Lucía) is a beguiling, intelligent being whose love of life and spontaneous nature challenge Horacio's ego as well as his assumptions about life. Oliveira's lover in Paris, she is lively, an active participant in her own adventures, and a stark contrast to Horacio's other friends, with whom he has formed a philosophical social circle called the Serpent Club. She eventually develops into an indispensable muse for Horacio and a lens he employs to examine himself and the world in a more three dimensional manner. La Maga also has an infant son, Rocamadour, whose appearance in France causes a crisis in the relationship between Lucía and Oliveira.

Apart from Horacio and La Maga, the other members of the Serpent Club include Ossip Gregorovius, who is presented as a rival for Lucía's affections, the artists Perico Romero and Etienne, Etienne's friend Guy Monod, Wong, and Ronald and Babs (who are married). The club meets either in La Maga's apartment or the flat Ronald and Babs share.

When Horacio returns to Argentina he is greeted by his old friend Manolo, nicknamed "Traveler", and his wife, Talita. The two are employed at a circus and seem to enjoy a mostly serene existence. Talita bears a striking similarity to Horacio's great love interest, La Maga, while Traveler is referred to as his "doppelgänger." The relationship that develops between the three centers around Oliveira's interest in Talita, which seems disingenuous, and Traveler's attempts to lessen Horacio's metaphysical burden. Oliveira desires to inhabit Traveler's life, while Traveler appears to be mostly concerned with his friend's deteriorating mental health.

Other major characters include Pola, another Parisian love interest of Horacio's, who is diagnosed with breast cancer after being cursed by La Maga; Gekrepten, Horacio's lover in Argentina; and Morelli, an Italian writer much discussed by the Serpent Club. Minor characters of note include Madame Berthe Trepat, a composer who mistakes Horacio's attention for sexual interest, and a homeless woman named Emmanuele with whom Oliveira has a brief, disastrous tryst shortly after La Maga's disappearance.

Main themes

[edit]Order vs. chaos

[edit]Horacio says of himself, "I imposed the false order that hides the chaos, pretending that I was dedicated to a profound existence while all the time it was the one that barely dipped its toe into the terrible waters" (end of chapter 21). Horacio's life follows this description as he switches countries, jobs, and lovers. The novel also attempts to resemble order while ultimately consisting of chaos. It possesses a beginning and an end but traveling from one to the other seems to be a random process. Horacio's fate is just as vague to the reader as it is to him. The same idea is perfectly expressed in improvisational jazz. Over several measures, melodies are randomly constructed by following loose musical rules. Cortázar does the same by using a loose form of prose, rich in metaphor and slang, to describe life.

Horacio vs. society

[edit]Horacio drifts from city to city, job to job, love to love, life to life, yet even in his nomadic existence he tries to find a sense of order in the world's chaos. He is always isolated: When he is with La Maga, he cannot relate to her; when he is with the Club, he is superior; when he is with Traveler and Talita, he fights their way of life. Even when with Morelli, the character he relates to most, there exists the social barriers of patient and orderly. Order versus chaos also exists in the structure of the novel, as in Morelli's statement, "You can read my book any way you want to” (556). At the end of chapter 56, he realizes that he is neither on 'the territory' (Traveler's side, with society) nor on 'the bedroom' (what would be his side, his real place, if he had reached it).

The conundrum of consciousness

[edit]One of the biggest arguments between Horacio and Ossip, one that threatens to put a rift in the club, is what Horacio deems "the conundrum of consciousness" (99). Does art prove consciousness? Or is it simply a continuation of instinctual leanings toward the collective brain? Talita argues a similar point in her seesaw-questions game with Horacio, who believes that only when one lives in the abstract and lets go of biological history can one achieve consciousness.

The definition of failure

[edit]Horacio's life seems hopeless because he has deemed himself a failure. La Maga's life seems hopeless because she has never worked to resolve the issues of rape and abuse in her childhood. Traveler's life seems hopeless because he has never done what he wanted to do, and even the name he has adopted teases at this irony. But none of these people are considered by outward society to be failures. They are stuck where they are because of their own self-defeating attitudes.

Short chapters also express the idea that there is no penetrating purpose to the novel and life in general. For Horacio, life is a series of artistic flashes by which he perceives the world in profound ways but still remains unable to create anything of value. Other major themes include obsession, madness, life-as-a-circus, the nature and meaning of sex, and self-knowledge.

Influences

[edit]The novel was the inspiration for Yuval Sharon's 2015 production of Hopscotch, an opera by six composers and six librettists set on multiple stages in Los Angeles.[6]

The Gotan Project's 2010 studio album Tango 3.0 includes a song "Rayuela" written in honor of the author.[7]

References

[edit]- ^ "National Book Awards – 1967". National Book Foundation. Retrieved 2012-03-11. – There was a "Translation" award from 1967 to 1983.

- ^ Chas Abdel-Nabi (16 October 2010). "The Bookshelf: Hopscotch". The Oxford Spokesman. Archived from the original on 15 July 2011. Retrieved 2011-02-06.

The novel is stream-of-consciousness and plays with the subjective mind of the reader.

- ^ "La novela que quiso que fueras libre". Brecha (in Spanish). 16 August 2019.

- ^ "Hopscotch: The Wacky Structure". evening all afternoon. 20 February 2010. Retrieved 10 April 2021.

- ^ Hopscotch Study Guide & Plot Summary.

- ^ "Opera on Location" by Alex Ross, The New Yorker (16 November 2015), pp. 46–51

- ^ "RAYUELA - NEW MUSIC VIDEO OUT NOW !". gotanproject.com. Archived from the original on 2010-10-07.

Further reading

[edit]- Hareau, Eliane; Sclavo, Lil (2018). El traductor, artífice reflexivo. Montevideo. ISBN 978-9974-93-195-4. Archived from the original on 2019-04-24. Retrieved 2019-02-13.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) There is a chapter devoted to the translation of "Hopscotch".

External links

[edit]- Julio Cortázar on Charlie Parker, Art and Dylan Thomas (circa 1958–63) (in Spanish)

- Julio Cortázar talks about Paris (circa 1963–67) (French / Spanish)

- Lost in Paris with Julio and Carole (circa 1977–82)

- "Un tal Morelli: Teoría y práctica de la lectura en Rayuela" by Santiago Juan-Navarro (in Spanish)

- Lisa Block de Behar; Jorge Ruffinelli; Carlos María Domínguez; et al. (2013-06-20). "Leída ayer, leída ahora" [Read yesterday, read today]. Brecha (in Spanish). (subscription required)

- "¿Y quién pagará esta llamada?"