Gavin Menzies

Gavin Menzies | |

|---|---|

| Born | Rowan Gavin Paton Menzies 14 August 1937 London |

| Died | 12 April 2020 (aged 82) |

| Occupation | Author, retired naval officer |

| Nationality | English |

| Genre | Pseudohistory |

| Notable works |

|

| Spouse | Marcella Menzies |

Rowan Gavin Paton Menzies (14 August 1937 – 12 April 2020)[1][2][3] was a British submarine lieutenant-commander who authored books claiming that the Chinese sailed to America before Columbus. Historians have rejected Menzies' theories and assertions[4][5][6][7][8]: 367–372 and have categorised his work as pseudohistory.[9][10][11]

He was best known for his controversial book 1421: The Year China Discovered the World, in which he asserts that the fleets of Chinese Admiral Zheng He visited the Americas prior to European explorer Christopher Columbus in 1492, and that the same fleet circumnavigated the globe a century before the expedition of Ferdinand Magellan. Menzies' second book, 1434: The Year a Magnificent Chinese Fleet Sailed to Italy and Ignited the Renaissance, extended his discovery hypothesis to the European continent. In his third book, The Lost Empire of Atlantis, Menzies claims that Atlantis did exist, in the form of the Minoan civilization, and that it maintained a global seaborne empire extending to the shores of America and India, millennia before actual contact in the Age of Discovery.

Biography

Menzies was born in London, England, and his family moved to China when he was three weeks old.[13] He was educated at Orwell Park Preparatory School in Suffolk, and Charterhouse.[14] Menzies dropped out of school when he was fifteen years old[15] and joined the Royal Navy in 1953.[16] He never attended university[15] and had no formal training in historical studies.[15] From 1959 to 1970, Menzies served on British submarines.[16] Menzies claims he sailed the routes sailed by Ferdinand Magellan and James Cook while he was commanding officer of the diesel submarine HMS Rorqual between 1968 and 1970,[16] a contention questioned by some of his critics.[17] He often refers back to his sea-faring days to support claims made in 1421.

In 1959, by his own account, Menzies was an officer on HMS Newfoundland on a voyage from Singapore to Africa, around the Cape of Good Hope, and on to Cape Verde and back to England. Menzies claimed that the knowledge of the winds, currents, and sea conditions that he gained on this voyage was essential to reconstructing the 1421 Chinese voyage that he discusses in his first book.[12] Critics have challenged the depth of his nautical knowledge.[17] In 1969, Menzies was involved in an incident in the Philippines, when Rorqual rammed a U.S. Navy minesweeper, USS Endurance, which was moored at a pier. This collision punched a hole in Endurance but did not damage Rorqual. The ensuing enquiry found Menzies and one of his subordinates responsible for a combination of factors that led to the accident, including the absence of the coxswain (who usually takes the helm in port) who had been replaced by a less experienced crew member, and technical issues with the boat's telegraph.[13]

Menzies retired the next year, and campaigned unsuccessfully as an independent candidate in Wolverhampton South West during the 1970 United Kingdom general election, where—standing against Enoch Powell—he called for unrestricted immigration to Great Britain, drawing 0.2% of the vote.[18] In 1990, Menzies began researching Chinese maritime history.[19][20][21] He had, however, no academic training and no command of the Chinese language, which his critics argue prevented him from understanding original source material relevant to his thesis.[22] Menzies trained as a barrister, but in 1996 he was declared a vexatious litigant by HM Courts Service which prohibited him from taking legal action in England and Wales without prior judicial permission.[8]: 371 ff. )[23] Menzies was made an honorary professor at Yunnan University in China.

1421: The Year China Discovered the World

Writing and research

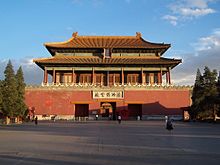

Gavin Menzies had the idea to write his first book after he and his wife Marcella visited the Forbidden City for their twenty-fifth wedding anniversary. Menzies noticed that they kept encountering the year 1421 and, concluding that it must have been an extraordinary year in world history, decided to write a book about everything that happened in the world in 1421. Menzies spent years working on the book and, by the time it was finished, it was a massive volume spanning 1,500 pages. Menzies sent the manuscript to an agent named Luigi Bonomi, who told him it was unpublishable, but was intrigued by a brief section of the book in which Menzies speculated about the voyages of Chinese admiral Zheng He and recommended that he rewrite the book, focusing it on Zheng He's voyages. Menzies agreed to rewrite it, but admitted that he was "not a natural writer" and requested Bonomi to rewrite the first three chapters for him.[15]

Bonomi contacted the firm Midas Public Relations to persuade a major newspaper to run a promotional article for Menzies's book. Menzies hired a room at the Royal Geographical Society, which convinced The Daily Telegraph to publish an article about his speculations. Publishers immediately began courting Menzies for the publishing rights to his book. Bantam Press, a division of Transworld Publishers, offered him £500,000 for the world publishing rights to it. At this point, Menzies's rewritten manuscript was only 190 pages. Bantam Press stated that the book possessed enormous marketing potential, but considered it to be poorly written and sloppily presented. According to Menzies, they told him, "You know, if you want to get your story over, you've got to make it readable, and you can't write, basically." During the revision process that followed, over 130 different people worked on the manuscript, with a large part being written by a ghostwriter named Neil Hanson. The authors relied entirely on Menzies for factual information and never brought in any fact checkers or reputable historians to make sure that the information in the book was accurate. After the rewriting process was complete, the book was at a publishable length of 500 pages.[15]

Publication, claims, and commercial success

The finished copy of the book was published in 2002 as 1421: The Year China Discovered the World (published as 1421: The Year China Discovered America in the United States).[15] The book is written informally, as a series of vignettes of Menzies' travels around the globe examining what he claims is evidence for his "1421 hypothesis", interspersed with speculation regarding the achievements of Admiral Zheng He's fleet.[7][15] Menzies states in the introduction that the book is an attempt to answer the question: "On some early European world maps, it appears that someone had charted and surveyed lands supposedly unknown to the Europeans. Who could have charted and surveyed these lands before they were 'discovered'?"

| External videos | |

|---|---|

In the book, Menzies concludes that only China had the time, money, manpower, and leadership to send such expeditions and then sets out to prove that the Chinese visited lands unknown in either China or Europe.[15] He claims that from 1421 to 1423, during the Ming dynasty of China under the Yongle Emperor, the fleets of Admiral Zheng He, commanded by the captains Zhou Wen, Zhou Man, Yang Qing, and Hong Bao, discovered Australia, New Zealand, the Americas, Antarctica, and the Northeast Passage; circumnavigated Greenland, tried to reach the North and South Poles, and circumnavigated the world before Ferdinand Magellan. 1421 instantly became an international success;[15] it was translated into dozens of different languages[24] and sold over a million copies.[15] It was listed as a New York Times best seller for several weeks in 2003.[25]

Although the book contains numerous footnotes, references, and acknowledgments, critics point out that it lacks supporting references for Chinese voyages beyond East Africa, the location acknowledged by professional historians as the limit of the fleet's travels.[26] Menzies bases his main theory on original interpretations and extrapolations of academic studies of minority population DNA, archaeological finds, and ancient maps. Many of these extrapolations draw on his personal nautical background without supporting evidence. Menzies claims that knowledge of Zheng He's discoveries was subsequently lost because the mandarin bureaucrats of the Ming imperial court feared that the costs of further voyages would ruin the Chinese economy. He conjectures that when the Yongle Emperor died in 1424 and the new Hongxi Emperor forbade further expeditions, the mandarins hid or destroyed the records of previous exploration to discourage further voyages.

Criticism

Mainstream Sinologists and professional historians have universally rejected 1421 and the alternative history of Chinese exploration described in it as pseudohistory.[4][27][6][15] A particular point of objection is Menzies' use of maps to argue that the Chinese mapped both the Eastern and Western hemispheres as they circumnavigated the world in the 15th century.[28] The widely respected British historian of exploration Felipe Fernández-Armesto dismissed Menzies as "either a charlatan or a cretin". Sally Gaminara, the publisher for Transworld, the company which publishes Menzies's book, dismissed Fernández-Armesto as merely jealous, commenting, "Well, maybe he'd like to have the same commercial success himself." On 21 July 2004, the Public Broadcasting System (PBS) broadcast a two-hour-long documentary debunking all of Menzies's major claims, featuring professional Chinese historians.[15] In 2004, historian Robert Finlay severely criticized Menzies in the Journal of World History for his "reckless manner of dealing with evidence" that led him to propose hypotheses "without a shred of proof".[7] Finlay wrote:

Unfortunately, this reckless manner of dealing with evidence is typical of 1421, vitiating all its extraordinary claims: the voyages it describes never took place, Chinese information never reached Prince Henry and Columbus, and there is no evidence of the Ming fleets in newly discovered lands. The fundamental assumption of the book—that the Yongle Emperor dispatched the Ming fleets because he had a "grand plan", a vision of charting the world and creating a maritime empire spanning the oceans—is simply asserted by Menzies without a shred of proof ... The reasoning of 1421 is inexorably circular, its evidence spurious, its research derisory, its borrowings unacknowledged, its citations slipshod, and its assertions preposterous ... Examination of the book's central claims reveals they are uniformly without substance.[29]

Tan Ta Sen, president of the International Zheng He Society, has acknowledged the book's popular appeal as well as its scholarly failings, remarking, "The book is very interesting, but you still need more evidence. We don't regard it as an historical book, but as a narrative one. I want to see more proof. But at least Menzies has started something, and people could find more evidence."[30]

A group of scholars and navigators—Su Ming Yang of the United States, Jin Guo-Ping and Malhão Pereira of Portugal, Philip Rivers of Malaysia, Geoff Wade of Singapore—questioned Menzies' methods and findings in a joint message:[26]

His book 1421: The Year China Discovered the World, is a work of sheer fiction presented as revisionist history. Not a single document or artifact has been found to support his new claims on the supposed Ming naval expeditions beyond Africa...Menzies' numerous claims and the hundreds of pieces of "evidence" he has assembled have been thoroughly and entirely discredited by historians, maritime experts and oceanographers from China, the U.S., Europe and elsewhere.[26]

Menzies created a website for his readers to send him any information they could find that might support his hypothesis.[15] Menzies said that his website was "a focal point for ongoing research into pre-Columbian exploration of the world."[31] In response, his devoted fans sent him thousands of pieces of purported evidence, which they claimed serve as proof that Menzies's ideas are correct.[15] Menzies also said that he used information his fans were sending to him to improve his hypotheses.[31] Academics have emphatically rejected all of this "evidence" as worthless and have criticized what American history professor Ronald H. Fritze calls the "almost cult-like" manner in which Menzies drummed up support for his hypothesis.[15] In reaction to this criticism, Menzies dismissed the experts' opinions as irrelevant, stating, "The public are on my side, and they are the people who count."[15]

A poll of History News Network readers ranked 1421 as the third-least credible history book in print.[32][33]

1434: The Year a Magnificent Chinese Fleet Sailed to Italy and Ignited the Renaissance

In 2008 Menzies released a second book entitled 1434: The Year a Magnificent Chinese Fleet Sailed to Italy and Ignited the Renaissance. In it Menzies claims that in 1434 Chinese delegations reached Italy and brought books and globes that, to a great extent, launched the Renaissance. He claims that a letter written in 1474 by Paolo dal Pozzo Toscanelli and found amongst the private papers of Columbus indicates that an earlier Chinese ambassador had direct correspondence with Pope Eugene IV in Rome. Menzies then claims that materials from the Chinese Book of Agriculture, the Nong Shu, published in 1313 by the Yuan-dynasty scholar-official Wang Zhen (fl. 1290–1333), were copied by European scholars and provided direct inspiration for the illustrations of mechanical devices which are attributed to the Italian Renaissance polymaths Taccola (1382–1453) and Leonardo da Vinci (1452–1519).

Felipe Fernández-Armesto, a professor of history at Tufts University in the United States and at Queen Mary, University of London, examined Menzies' claim that private papers of Columbus indicate a Chinese ambassador in correspondence with the Pope and called this claim "drivel." He states that no reputable scholar supports the view that Toscanelli's letter refers to a Chinese ambassador.[34] Martin Kemp, Professor of the History of Art at Oxford University, questions the rigor of Menzies' application of the historical method, and in regard to European illustrations purporting to be copied from the Chinese Nong Shu, writes that Menzies "says something is a copy just because they look similar. He says two things are almost identical when they are not."[34]

In regard to Menzies' theory that Taccola's sketches are based on Chinese information, Captain P.J. Rivers writes that Menzies contradicts himself by saying elsewhere in his book that Taccola had started his work on his technical sketches in 1431, when Zheng He's fleet was still assembled in China, and that the Italian engineer finished his technical sketches in 1433—one year before the purported arrival of the Chinese fleet.[35] Geoff Wade, a senior research fellow at the Asia Research Institute of the National University of Singapore, acknowledges that there was a cross exchange of technological ideas between Europe and China, but ultimately classifies Menzies' book as historical fiction and asserts that there is "absolutely no Chinese evidence" for a maritime venture to Italy in 1434.[34]

Albrecht Heeffer investigated Menzies' claim that Regiomontanus based his solution to the Chinese remainder theorem on the Chinese work Mathematical Treatise in Nine Sections from 1247. He arrived at the conclusion that the solution method does not depend on this text but on the earlier Sunzi Suanjing as does the treatment of a similar problem by Fibonacci which predates the Mathematical Treatise in Nine Sections. Furthermore, Regiomontanus could rely on practices with remainder tables from the abacus tradition.[36]

References

- ^ "Contemporary Authors: Gavin Menzies". Highbeam Research. 2006. Archived from the original on 5 November 2012. Retrieved 24 March 2011.

- ^ "Lt Cdr Gavin Menzies, submariner turned author of far-fetched oceanic histories – obituary". The Daily Telegraph. 14 May 2020.

- ^ "Gavin Menzies: August 14th 1937– April 12th, 2020". 18 April 2020. Retrieved 14 May 2020.

- ^ a b "The 1421 myth exposed". 1421exposed.com. Archived from the original on 28 March 2007. Retrieved 2 October 2009.

- ^ Zheng He in the Americas and Other Unlikely Tales of Exploration and Discovery, archived from the original on 17 March 2007, retrieved 22 March 2007

- ^ a b Gordon, Peter (30 January 2003). "1421: The Year China Discovered the World by Gavin Menzies". Asian Review of Books. Archived from the original on 5 July 2003. Retrieved 2 November 2023.

- ^ a b c Finlay 2004

- ^ a b Goodman, David S. G. (2006). "Mao and The Da Vinci Code: Conspiracy, Narrative and History". The Pacific Review. 19 (3): 359–384. doi:10.1080/09512740600875135. S2CID 144521610.

- ^ Fritze, Ronald H. (2011). Invented Knowledge: False History, Fake Science and Pseudo-religions (Reprint ed.). Reaktion Books. pp. 12, 19. ISBN 978-1861898173.

- ^ Melleuish, Greg; Sheiko, Konstantin; Brown, Stephen (1 November 2009). "Pseudo History/Weird History: Nationalism and the Internet". History Compass. 7 (6): 1484–1495. doi:10.1111/j.1478-0542.2009.00649.x.

- ^ Henige, David (July 2008). "The Alchemy of Turning Fiction into Truth" (PDF). Journal of Scholarly Publishing. 39 (4): 354–372. doi:10.3138/jsp.39.4.354. Retrieved 10 October 2013.

- ^ a b Menzies, Gavin. 1421: The Year China Discovered America (2008 ed.). p. 113.

- ^ a b Interview with Gavin Menzies, Australian Broadcasting Corporation, retrieved 22 March 2007

- ^ "The Times Guide to the House of Commons, 1970", Times Newspapers Ltd, 1970, p. 231.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r Fritze, Ronald H. (2009). Invented Knowledge: False History, Fake Science and Pseudo-Religions. London, England: Reaktion Books. pp. 96–103. ISBN 978-1-86189-430-4.

- ^ a b c Houterman, Hans; Koppes, Jeroen (2011). "Naval Officers (RN, RNR & RNVR) 20th Century (non-World War II)". unithistories.com. Retrieved 23 June 2011.

1968–1970, Commanding Officer, HMS Rorqual

- ^ a b Challenges to Menzies' nautical experience, archived from the original on 10 June 2007, retrieved 22 March 2007; see esp. note 5 of the Appendix.

- ^ Evans, Peter (5 June 1970). "Immigrant girl will vote in despair – Powellism". News. The Times. No. 57888. London. col C, p. 9.

- ^ Menzies, Gavin (11 May 2007). "When the East Discovered the West". Archived from the original on 20 March 2012. Retrieved 22 March 2011.

- ^ "Gavin Menzies: Mad as a Snake or a Visionary?". The Daily Telegraph. 1 August 2008. Retrieved 22 March 2011.

- ^ Chua, Dan-Chyi (29 December 2008). "Did the Chinese Discover America?". The Asia Mag. Archived from the original on 17 March 2012. Retrieved 2 November 2023.

- ^ Ptak, Roderich; Salmon, Claudine (2005), "Zheng He: Geschichte und Fiktion", in Ptak, Roderich; Höllmann, Thomas O. (eds.), Zheng He. Images & Perceptions, South China and Maritime Asia, vol. 15, Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz Verlag, pp. 9–35 (12)

- ^ "Vexatious litigants". HM Courts & Tribunals Service. 15 December 2014. Retrieved 16 June 2019.

- ^ Hitt, Jack (5 January 2003). "Goodbye, Columbus!". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 12 March 2011.

rights

- ^ "BEST SELLERS: January 26, 2003 – Page 2". The New York Times. 26 January 2003. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 12 March 2011.

- ^ a b c Guo-Ping, J; Pereira, M; Rivers PJ; Ming-Yang S; Wade G (2006). "Joint Statement on the Claims by Gavin Menzies Regarding the Zheng He Voyages". 1421exposed.com. Archived from the original on 10 June 2007. Retrieved 10 October 2009.

- ^ Newbrook, M (2004), "Zheng He in the Americas and Other Unlikely Tales of Exploration and Discovery", Skeptical Briefs, 14 (3), archived from the original on 27 August 2011, retrieved 10 October 2009.

- ^ Wade, Geoff (Autumn 2007). "The "Liu/Menzies" World Map: A Critique" (PDF). E-Perimetron. 2: 270.

- ^ Finlay 2004, pp. 241f.

- ^ Kolesnikov-Jessop, Sonia (25 June 2005), "Did Chinese beat out Columbus?", The New York Times, retrieved 8 June 2010.

- ^ a b "Official website". Gavin Menzies. Retrieved 16 June 2019.

- ^ Walsh, David Austin (16 July 2012). "What is the Least Credible History Book in Print?". History News Network. Retrieved 7 May 2020.

- ^ "History News Network Celebrates Bad History Books". The New York Times. 4 July 2012. Retrieved 17 January 2015.

- ^ a b c Castle, Tim (29 July 2008). "Columbus debunker sets sights on Leonardo da Vinci". Reuters. London. Archived from the original on 23 December 2008. Retrieved 26 January 2011.

- ^ The 1421 myth exposed: 1434 – No Way – No Canal. Retrieved 13 June 2012.

- ^ Heeffer, Albrecht (2008). "Regiomontanus and Chinese Mathematics". Philosophica. 82: 87–114. doi:10.21825/philosophica.82169. hdl:1854/LU-1092888. S2CID 170479588.

External links

- Gavin Menzies' website

- Australian Broadcasting Corporation's FOUR CORNERS Program Transcript of "Junk History"

- Criticism

- 1421 Exposed – Website set up by an international group of academics and researchers

- Finlay, Robert (2004), "How Not to (Re)Write World History: Gavin Menzies and the Chinese Discovery of America" (PDF), Journal of World History, 15 (2): 229, doi:10.1353/jwh.2004.0018, S2CID 144478854, archived from the original (PDF) on 9 November 2013

- Wade, Geoff (2007), "The "Liu/Menzies" World Map: A Critique" (PDF), E-Perimetron, 2 (4): 273–80, ISSN 1790-3769

- Hartz, Bill. In the Hall of Ma'at. Weighing the Evidence for Alternative History: Gavin's Fantasy Land, 1421 Archived 14 October 2013 at the Wayback Machine

- Esler, Lloyd (7 August 2019). "A Chinese whopper – no evidence of a Chinese city in New Zealand". The Southland Times.