Battle of Muye

This article needs additional citations for verification. (August 2019) |

| Battle of Muye | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| Shang | Zhou | ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| King Zhou of Shang | |||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 50,000–70,000 troops |

| ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| Heavy | |||||||

| Battle of Muye | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional Chinese | 牧野之戰 | ||||||||

| Hanyu Pinyin | Mùyě zhī zhàn | ||||||||

| |||||||||

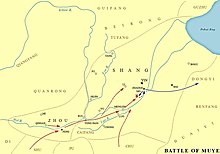

The Battle of Muye, Mu, or Muh (c. 1046 BC)[a][b] was fought between forces of the ancient Chinese Shang dynasty led by King Zhou of Shang and the rebel state of Zhou led by King Wu. The Zhou defeated the Shang at Muye and captured the Shang capital Yin, marking the end of the Shang and the establishment of the Zhou dynasty—an event that features prominently in Chinese historiography as an example of the Mandate of Heaven theory that functioned to justify dynastic conquest throughout Chinese history.

Background

[edit]By the 12th century BC, Shang influence extended west to the Wei River valley, a region that was occupied by clans known as the Zhou. King Wen of Zhou, the ruler of the Zhou and vassal of the Shang king, was given the title "Overlord of the West"[1] by Di Xin of Shang (King Zhou).[c] Di Xin used King Wen to guard his rear while he was involved in a south-eastern campaign.

Eventually, Di Xin came to fear King Wen's growing power and imprisoned him. Although Wen was later released, the tension between Shang and Zhou grew. Wen prepared his army and conquered a few smaller states which were loyal to Shang, slowly weakening Shang's allies. King Wen died in 1050 BC before Zhou's actual offensive against Shang.

Di Xin did not stress about Zhou's local conquests in the Wei River valley, as he viewed himself as a rightful ruler, appointed by his divine ancestors. Other records describe him as overindulging in alcohol and sex with his consort Daji.

King Wen's son King Wu of Zhou led the Zhou in a revolt a few years later. The reason for this delay was that King Wu believed that the heavenly order to conquer Shang had not been given, as well as the advice of Jiang Ziya to wait for the right opportunity.

Sentiment towards Di Xin is difficult to gauge. Subsequent histories were politically and culturally aligned with the conquering Zhou, and historical accounts of Di Xin grew more egregious over time. In earlier sources, he is depicted as benighted and ineffectual; whereas after a few centuries, he is described as a monstrous torturer, universally despised.[2]

Battle

[edit]With just 45,000 men and a few hundred wagons, the Zhou were initially hugely outnumbered – even though most of the Shang forces were at war to the east, Di Xin of Shang organized some 170,000 troops. But Di Xin made a mistake: many of his fighters were slaves, and he thought that despite low troop morale, his army's superior numbers could, if not defeat, then at least slow down the rebels until reinforcements could arrive. He was wrong. The majority of his Shang troops fled or joined the Zhou, and the few who did were easily overwhelmed by the Zhou forces. After the battle, Di Xin committed suicide.[3][4][5]

Still, many loyal Shang troops fought on, and a very bloody battle followed, depicted at the end of a poem in the Shijing:

The troops of Yin-Shang,

Were collected like a forest,

And marshaled in the wilderness of Muh.

...

The wilderness of Muh spread out extensively;

Bright shone the chariots of sandal;

The teams of bays, black-maned and white-bellied, galloped along;

The grand-master Shang-foo,

Was like an eagle on the wing,

Assisting king Woo,

Who at one onset smote the great Shang.

The Zhou troops were much better trained, and their morale was high. In one of the chariot charges, King Wu broke through the Shang's defense line. Di Xin was forced to flee to his palace, and the remaining Shang troops fell into further chaos. The Zhou were victorious and showed little mercy to the defeated Shang, shedding enough blood "to float a log".

Aftermath

[edit]After the battle, Di Xin burned himself to death in his palace on the Deer Terrace Pavilion.[7] A later tradition has Di Xin covering himself with precious jades prior to immolation.[10] King Wu killed Daji after he found her. The order to execute her was given by Jiang Ziya. Shang officials were released without charge with some later working as Zhou officials. The imperial grain store was opened immediately after the battle to feed the starving population. The battle marked the end of the Shang dynasty and the beginning of the Zhou dynasty.

Dating

[edit]Although the day and month on which the Battle of Muye was fought are certain, there is doubt about the year.[11] Prior to the Xia–Shang–Zhou Chronology Project, previous chronologies had proposed at least 44 different dates for this event, ranging from 1130 to 1018 BC.[12][13] The most popular had been 1122 BC, calculated by the Han dynasty astronomer Liu Xin, and 1027 BC, deduced from a statement in the "old text" Bamboo Annals that the Western Zhou (whose endpoint is known to be 770 BC) had lasted 257 years.[14][15]

A few documents relate astronomical observations to this event:

- A quotation in the Book of Han from the lost Wǔchéng 武成 chapter of the Book of Documents appears to describe a lunar eclipse just before the beginning of King Wu's campaign. This date, and the date of his victory, are given as months and sexagenary days.[16][17]

- A passage in the Guoyu gives the positions of the Sun, Moon, Jupiter, and two stars on the day King Wu attacked the Shang.[15][17]

- The "current text" Bamboo Annals mentions conjunctions of all five planets occurring before and after the Zhou conquest. Han-period texts mention the first conjunction as occurring in the 32nd year of the reign of the last king. Such events are rare, but all five planets did gather on 28 May 1059 BC and again on 26 September 1019 BC. Although the recorded positions in the sky of these two events are the reverse of what occurred, they could not have been retrospectively calculated at the time the account first appears.[18]

The strategy adopted by the Project was to use the archeological investigation to narrow the range of dates that would need to be compared with the astronomical data. Although no archaeological traces of King Wu's campaign have been found, the pre-conquest Zhou capital at Fengxi in Shaanxi has been excavated and strata at the site have been identified with the pre-dynastic Zhou. Radiocarbon dating of samples from the site as well as at late Yinxu and early Zhou capitals, using the wiggle matching technique, yielded a date for the conquest between 1050 and 1020 BC. The only date within that range matching all the astronomical data is 20 January 1046 BC. This date had previously been proposed by David Pankenier, who had matched the above passages from the classics with the same astronomical events, but here it resulted from a thorough consideration of a broader range of evidence.[19][20][21]

Other scholars have raised several criticisms of this process. The connection between the layers at the archaeological sites and the conquest is uncertain.[22] The narrow range of radiocarbon dates is cited with a less stringent confidence interval (68%) than the standard requirement of 95%, which would have produced a much wider range.[23] The texts describing the relevant astronomical phenomena are extremely obscure.[24][25] For example, the inscription on the Li gui, a key text used in dating the conquest, can be interpreted in several different ways, with one alternative reading leading to the date of 9 January 1044 BC.[15]

References

[edit]Footnotes

[edit]- ^ a b 1046 BC is the year endorsed by the Xia–Shang–Zhou Chronology Project, though doubts persist on this dating. See § Dating.

- ^ literally, "Battle of the Wild Pasture"

- ^ The Shang monarch's name is recorded as "Di Xin" (帝辛, "God-King Xin") in Shang records. Zhou records call him by many names, using his posthumous epithet "Zhou" (紂). These include "Zhouxin", "Zhou of Shang", "Zhou of Yin" (his capital city), and "Shang King Zhou". This name "Zhòu" is an entirely different word to the Zhōu dynasty that conquered him (周), despite their identical romanization when tone marks are ignored. "Di Xin" is used here to avoid confusion.

- ^ The final words of this poem, "會朝清明", do not have an agreed-upon meaning, even accounting for poetic variation. Legge (1871) has "That morning's encounter was followed by a clear bright [day]."[6] Shaughnessy (1999) and Chen (2021) give "Meeting in the morning, clear and bright."[7][8] Nivison (2018) reads the final two words as a date term, yielding "this occurred in the morning, Qingming [Day]".[9]

Citations

[edit]- ^ Pines (2020), p. 717.

- ^ Pines (2008), pp. 3–4, 10, 12.

- ^ Ph.D, Alfred J. Andrea (2011-03-23). World History Encyclopedia: [21 volumes]. Bloomsbury Publishing USA. ISBN 978-1-85109-930-6.

- ^ Li, Xiaobing (2012-01-10). China at War: An Encyclopedia. Bloomsbury Publishing USA. ISBN 978-1-59884-416-0.

- ^ Grant, R. G. (2017-10-24). 1001 Battles That Changed the Course of History. Book Sales. ISBN 978-0-7858-3553-0.

- ^ Legge (1871), p. 436.

- ^ a b Shaughnessy (1999), p. 310.

- ^ Chen (2021), p. 181.

- ^ Nivison (2018), p. 113.

- ^ Grebnev (2018), pp. 86–87.

- ^ Wu (1982), p 319 n 40, p 320 n 41.

- ^ Yin (2002), p. 1.

- ^ Lee (2002), p. 32.

- ^ Pankenier (1982), p. 3.

- ^ a b c Lee (2002), p. 34.

- ^ Lee (2002), pp. 33–34.

- ^ a b Liu (2002), p. 4.

- ^ Zhang (2002), p. 350.

- ^ Lee (2002), pp. 31–34.

- ^ Yin (2002), pp. 2–3.

- ^ Pankenier (1982), pp. 3–7.

- ^ Lee (2002), p. 36.

- ^ Keenan (2007), p. 147.

- ^ Keenan (2002), pp. 62–64.

- ^ Stephenson (2008), pp. 231–242.

Sources

[edit]- Chen, Hung-Sen (2021). "Some Minor Insights from Reading the Anhui University Warring States Bamboo Slips of the Classic of Poetry". Bamboo and Silk. 4. Brill: 172–188. doi:10.1163/24689246-00401006. S2CID 234008212.

- Grebnev, Yegor (2018). "The Record of King Wu of Zhou's Royal Deeds in the Yi Zhou shu in Light of Near Eastern Royal Inscriptions". Journal of the American Oriental Society. 138 (1). University of Michigan: American Oriental Society: 73–104. doi:10.7817/jameroriesoci.138.1.0073. JSTOR 10.7817/jameroriesoci.138.1.0073.

- Keenan, Douglas J. (2002). "Astro-historiographic chronologies of early China are unfounded" (PDF). East Asian History. 23. The Australian National University: 61–68.

- Keenan, Douglas J. (2007). "Defence of planetary conjunctions for early Chinese chronology is unmerited" (PDF). Journal of Astronomical History and Heritage. 10 (2). National Astronomical Research Institute of Thailand: 142–147. doi:10.3724/SP.J.1440-2807.2007.02.08. S2CID 17634444.

- Lee, Yun Kuen (2002). "Building the Chronology of early Chinese History". Asian Perspectives. 41 (1). University of Hawai`i Press: 15–42. doi:10.1353/asi.2002.0006. hdl:10125/17161. JSTOR 42928543. S2CID 67818363.

- The She king, or the Book of poetry: pt. 1. The first part of the She-king, or the Lessons from the states; and the Prolegomena. pt. II. The second, third, and fourth parts of the She-king, or the Minor odes of the kingdom, the Greater odes of the kingdom, the Sacrificial odes and praise-songs; and the indexes. The Chinese Classics. Translated by Legge, James. 1871.

- Liu, Ci-yuan (2002). "Astronomy in the Xia-Shang-Zhou Chronology Project". Journal of Astronomical History and Heritage. 5 (1). National Astronomical Research Institute of Thailand: 1–8. Bibcode:2002JAHH....5....1L. doi:10.3724/SP.J.1440-2807.2002.01.01. S2CID 129674512.

- Nivison, David S. (2018). Adam C. Schwartz (ed.). The Nivison Annals: Selected Works of David S. Nivison on Early Chinese Chronology, Astronomy, and Historiography. De Gruyter Mouton. Bibcode:2018nasw.book.....N. doi:10.1515/9781501505393. ISBN 9781501505393. S2CID 165998984.

- Pankenier, David W. (1982). "Astronomical Dates in Shang and Western Zhou" (PDF). Early China. 7. Cambridge University Press: 2–37. doi:10.1017/S0362502800005599. JSTOR 23351672. S2CID 163543848.

- Pines, Yuri (2008). "To Rebel is Justified? The Image of Zhouxin and the Legitimacy of Rebellion in the Chinese Political Tradition". Oriens Extremus. 47. Harrassowitz Verlag: 1–24. JSTOR 24048044.

- Pines, Yuri (2020). "Names and Titles in Eastern Zhou Texts". T'oung Pao. 106 (5–6). Leiden: Brill: 714–720. doi:10.1163/15685322-10656P06. S2CID 234449375.

- Shaughnessy, Edward L. (1999). "Western Zhou History". In Loewe, Michael; Shaughnessy, Edward L. (eds.). The Cambridge History of Ancient China: from the Origins of civilization to 221 BC. Cambridge University Press. pp. 292–351. doi:10.1017/CHOL9780521470308.007. ISBN 9780521470308.

- Sima Qian; Sima Tan (1959) [90s BCE]. "4: 周本紀". Shiji 史記 [Records of the Grand Historian]. Zhonghua Shuju.

- Stephenson, F. Richard (2008). "How reliable are archaic records of large solar eclipses?". Journal for the History of Astronomy. 39 (2). SAGE Publications: 229–250. Bibcode:2008JHA....39..229S. doi:10.1177/002182860803900205. S2CID 117346649.

- Wu, Kuo-Cheng (1982). The Chinese Heritage. New York: Crown Publishers. ISBN 0-517-54475-X.

- Yin Weizhang (2002). "New development in the research on the chronology of the Three Dynasties" (PDF). Chinese Archaeology. 2. Translated by Victor Cunrui Xiong. Chinese Academy of Social Sciences: 1–5. doi:10.1515/char.2002.2.1.1. S2CID 134396442.

- Zhang Peiyu (2002). "Determining Xia–Shang–Zhou Chronology through Astronomical Records in Historical Texts". Journal of East Asian Archaeology. 4. Brill: 335–357. doi:10.1163/156852302322454602.