Morrill Tariff

- Northwest Ordinance

- Kentucky and Virginia Resolutions

- End of Atlantic slave trade

- Missouri Compromise

- Tariff of 1828

- Nat Turner's Rebellion

- Nullification crisis

- End of slavery in British colonies

- Texas Revolution

- United States v. Crandall

- Gag rule

- Commonwealth v. Aves

- Murder of Elijah Lovejoy

- Burning of Pennsylvania Hall

- American Slavery As It Is

- United States v. The Amistad

- Prigg v. Pennsylvania

- Texas annexation

- Mexican–American War

- Wilmot Proviso

- Nashville Convention

- Compromise of 1850

- Uncle Tom's Cabin

- Recapture of Anthony Burns

- Kansas–Nebraska Act

- Ostend Manifesto

- Bleeding Kansas

- Caning of Charles Sumner

- Dred Scott v. Sandford

- The Impending Crisis of the South

- Panic of 1857

- Lincoln–Douglas debates

- Oberlin–Wellington Rescue

- John Brown's raid on Harpers Ferry

- Virginia v. John Brown

- 1860 presidential election

- Crittenden Compromise

- Secession of Southern states

- Peace Conference of 1861

- Corwin Amendment

- Battle of Fort Sumter

The Morrill Tariff was an increased import tariff in the United States that was adopted on March 2, 1861, during the administration of US President James Buchanan, a Democrat. It was the twelfth of the seventeen planks in the platform of the incoming Republican Party, which had not yet been inaugurated, and the tariff appealed to industrialists and factory workers as a way to foster rapid industrial growth.[1]

It was named for its sponsor, Representative Justin Smith Morrill of Vermont, who drafted it with the advice of the economist Henry Charles Carey. The eventual passage of the tariff in the US Senate was assisted by multiple opponent senators from the South resigning from Congress after their states declared their secession from the Union. The tariff rates were raised to both make up for a federal deficit that had led to increased government debt in recent years and to encourage domestic industry and foster high wages for industrial workers.[2]

The Morrill Tariff replaced a lower Tariff of 1857 which, according to historian Kenneth Stampp, had been developed in response to a federal budget surplus in the mid-1850s.[3]

Two additional tariffs sponsored by Morrill, each higher than the previous one, were passed under President Abraham Lincoln to raise revenue that was urgently needed during the American Civil War.

The tariff inaugurated a period of continuous protectionism in the United States, and that policy remained until the adoption of the Revenue Act of 1913, or Underwood Tariff. The schedule of the Morrill Tariff and both of its successors were retained long after the end of the Civil War.

History

[edit]

Origins

[edit]Tariff in United States history has often been made high to encourage the development of domestic industry, and had been advocated, especially by the Whig Party and its longtime leader, Henry Clay. Such a tariff was enacted in 1842, but in 1846 the Democratic Party enacted the Walker Tariff, which cut tariff rates substantially. The Democrats cut rates even further in the Tariff of 1857, which was highly favorable to the South.

Meanwhile, the Whig Party collapsed, and tariffs were taken up by the new Republican Party, which ran its first national ticket in 1856. Some former Whigs from the border states and the Upper South remained in Congress as "Opposition," "Unionist," or "American," (Know Nothing) members and supported higher tariffs.

The Panic of 1857 led to calls for protectionist tariff revision. The famous economist Henry C. Carey blamed the panic on the new tariff. His opinion was widely circulated in the protectionist media for higher tariffs.

Efforts to raise the tariffs began in earnest in the 35th Congress of 1857–1859. Two proposals were submitted in the US House of Representatives.

House Ways and Means Committee Chairman John S. Phelps, Democrat from Missouri, wrote the Democrats' plan, which retained most of the low rates of the Tariff of 1857, with minor revisions to stimulate revenue.

Ways and Means members Morrill and Henry Winter Davis, a Maryland "American," produced the Republican proposal to raise the tariffs. It replaced the existing ad valorem tariff schedule with specific duties and drastically increased tariff rates on goods that were produced by popular "protected" industries, such as iron, textiles, and other manufactured goods. The economic historian Frank Taussig argued that in many cases, the substitution of specific duties was used to disguise the extent of the rate increases.[citation needed] Supporters of the specific rates argued that they were necessary because European exporters routinely provided US customers with fake invoices showing lower prices for goods than were actually paid. Specific rates made such subterfuge pointless.

However, the House took no action on either tariff bill during the 35th Congress.

House actions

[edit]

When the 36th Congress met in 1859, action remained blocked by a dispute until 1860 over who would be elected the Speaker of the House. In 1860, the Republican William Pennington of New Jersey was elected as speaker. Pennington appointed a pro-tariff Republican majority to the Ways and Means Committee, with John Sherman of Ohio its chairman.

The Morrill bill was passed out of the Ways and Means Committee. Near the end of first session of the Congress (December 1859–June 1860), on May 10, 1860, the bill was brought up for a floor vote and passed 105–64.[4]

The vote was largely but not entirely sectional. Republicans, all from the northern states, voted 89–2 for the bill. They were joined by 7 northern Democrats from New York, New Jersey, and Pennsylvania. Five of them were "anti-Lecompton Democrats," who opposed the pro-slavery Lecompton Constitution for Kansas.

Also, 14 northern Democrats voted against the bill.

In the Border States, four "Opposition" Representatives from Kentucky voted for it, as did its cosponsor, Winter of Maryland, a Maryland "Unionist," and a Democrat from Delaware. Eight Democrats from the Border States and a member of the American Party from Missouri voted against it.

Thirty-five southern Democrats and three Oppositionists voted against it; one Oppositionist from Tennessee voted for it.

Thus the sectional breakdown was 96–15 in the North, 7–9 in the Border States, and 1–39 in the South.

There were 55 abstentions, including 13 Republicans, 12 northern Democrats, 13 southern Democrats, and 8 southern "Oppositionists" and "Americans." (The remaining Representatives were mostly "paired" with opposing Representatives who could not be present.[5]

Senate action

[edit]The Morrill bill was sent on to the US Senate. However, the Senate was controlled by Democrats and so it was bottled up in the Finance Committee, chaired by Robert M. T. Hunter of Virginia.

That ensured that the Senate vote would be put off until the second session in December 1860 and meant that the tariff would be a prominent issue in the 1860 election.[6]

1860 election

[edit]The Republican Party included a strong pro-tariff plank in its 1860 platform and sent prominent tariff advocates touting the bill, such as Morrill and Sherman, to campaign in Pennsylvania and New Jersey, where the tariff was popular. Both Democratic candidates, John C. Breckinridge and Stephen Douglas, opposed all high tariffs and protectionism in general.[7]

The historian Reinhard H. Luthin documents the importance of the Morrill Tariff to the Republicans in the 1860 presidential election.[8] Lincoln's record as a protectionist and support for the Morrill bill, he notes, helped him to secure support in the important state of Pennsylvania and neighboring New Jersey. Lincoln carried Pennsylvania handily in November, as part of his sweep of the North.

On February 14, 1861, President-elect Lincoln told an audience in Pittsburgh that he would make a new tariff his priority in the next session if the bill did not pass by his inauguration, on March 4.

Renewed Senate action

[edit]The second session of the 36th Congress began in December 1860. At first, it appeared that Hunter would keep the Morrill bill tabled until the end of the term in March.

However, in December 1860 and January 1861, seven southern states seceded, and their low-tariff senators withdrew. Republicans took control of the Senate in February, and Hunter lost his hold on the Finance Committee.

Meanwhile, the Treasury was in financial crisis, with less than $500,000 on hand and millions in unpaid bills. The Union urgently needed new revenue. A recent historian concludes that "the impetus for revising the tariff arose as an attempt to augment revenue, stave off 'ruin,' and address the accumulating debt."[9]

The Morrill bill was brought to the Senate floor for a vote on February 20 and passed 25 to 14. The vote was split almost completely down party lines. It was supported by 24 Republicans and the Democrat William Bigler of Pennsylvania. It was opposed by 10 Southern Democrats, 2 Northern Democrats, and 2 Far West Democrats. Twelve Senators abstained, including 3 Northern Democrats, 1 California Democrat, 5 Southern Democrats, 2 Republicans, and 1 Unionist from Maryland.[10]

There were some minor amendments related to the tariffs on tea and coffee, which required a conference committee with the House, but they were resolved, and the final bill was approved by unanimous consent on March 2.

Though a Democrat himself, President James Buchanan favored the bill because of the interests of his home state, Pennsylvania. He signed the bill into law as one of his last acts in office.

Adoption and amendments

[edit]The tariff took effect one month after it was signed into law. Besides setting tariff rates, the bill altered and restricted the Warehousing Act of 1846.

The tariff was drafted and passed the House before the Civil War began or was expected, and it was passed by the Senate after seven States had seceded.

At least one author has argued that the first Morrill should not be considered "Civil War" legislation.[11]

In fact, the tariff proved to be too low for the revenue needs of the Civil War and was quickly raised by the Second Morrill Tariff, or Revenue Act of 1861, later that Fall.[12]

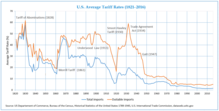

Impact

[edit]In its first year of operation, the Morrill Tariff increased the effective rate collected on dutiable imports by approximately 70%. In 1860, American tariff rates were among the lowest in the world and also at historical lows by 19th-century standards, the average rate for 1857 to 1860 being around 17% overall (ad valorem), 21% on dutiable items only. The Morrill Tariff immediately raised those averages to about 26% overall, or 36% on dutiable items. Further increases by 1865 left the comparable rates at 38% and 48%. Although higher than in the immediate antebellum period, the new rates were still significantly lower than between 1825 and 1830, when rates had sometimes been over 50%.[13]

The United States needed $3 billion to pay for the immense armies and fleets raised to fight the Civil War, over $400 million for 1862 alone. The chief source of revenue had been tariffs. Therefore, Secretary of the Treasury Salmon P. Chase, despite being a longtime free-trader, worked with Morrill to pass a second tariff bill in summer 1861, which raised rates another 10% to generate more revenue.[14] The subsequent bills were primarily revenue driven to meet the war's needs but enjoyed the support of protectionists such as Carey, who again assisted Morrill in the bill's drafting.

However, the tariff played only a modest role in financing the war and was far less important than other measures, such as $2.8 billion in bond sales and some printing of greenbacks. Customs revenue from tariffs totaled $345 million from 1861 to 1865, or 43% of all federal tax revenue, but military spending totaled $3,065 million.[15]

Reception abroad

[edit]The Morrill Tariff was met with intense hostility in Britain, where free trade dominated public opinion. Southern diplomats and agents sought to use British ire towards the Morrill Tariff to garner sympathy, with the aim of obtaining British recognition for the Confederacy.[16] The new tariff schedule heavily penalized British iron, clothing, and manufactured exports by making them more costly and sparked public outcry from many British politicians. The expectation of high tax rates probably caused British shippers to hasten their deliveries before the new rates took effect in the early summer of 1861.

When complaints were heard from London, Congress counterattacked. The Senate Finance Committee chairman snapped, "What right has a foreign country to make any question about what we choose to do?"[17]

When the American Civil War broke out in 1861, British public opinion was sympathetic to the Confederacy, in part because of lingering agitation over the tariff. As one diplomatic historian has explained, the Morrill Tariff:[18]

not unnaturally gave great displeasure to England. It greatly lessened the profits of the American markets to English manufacturers and merchants, to a degree which caused serious mercantile distress in that country. Moreover, the British nation was then in the first flush of enthusiasm over free trade, and, under the lead of extremists like Cobden and Gladstone, was inclined to regard a protective tariff as essentially and intrinsically immoral, scarcely less so than larceny or murder. Indeed, the tariff was seriously regarded as comparable in offensiveness with slavery itself, and Englishmen were inclined to condemn the North for the one as much as the South for the other. "We do not like slavery," said Palmerston to Adams, "but we want cotton, and we dislike very much your Morrill tariff."

Many prominent British writers condemned the Morrill Tariff in the strongest terms. The economist William Stanley Jevons denounced it as a "retrograde" law. The famous novelist Charles Dickens used his magazine, All the Year Round, to attack the new tariff. On December 28, 1861, Dickens published a lengthy article, believed to be written by Henry Morley,[19] which blamed the American Civil War on the Morrill Tariff:

If it be not slavery, where lies the partition of the interests that has led at last to actual separation of the Southern from the Northern States?... Every year, for some years back, this or that Southern state had declared that it would submit to this extortion only while it had not the strength for resistance. With the election of Lincoln and an exclusive Northern party taking over the federal government, the time for withdrawal had arrived.... The conflict is between semi-independent communities [in which] every feeling and interest [in the South] calls for political partition, and every pocket interest [in the North] calls for union.... So the case stands, and under all the passion of the parties and the cries of battle lie the two chief moving causes of the struggle. Union means so many millions a year lost to the South; secession means the loss of the same millions to the North. The love of money is the root of this, as of many other evils.... [T]he quarrel between the North and South is, as it stands, solely a fiscal quarrel.

Others, such as John Stuart Mill, denied tariffs had anything to do with the conflict:

...what are the Southern chiefs fighting about? Their apologists in England say that it is about tariffs, and similar trumpery. They say nothing of the kind. They tell the world, and they told their own citizens when they wanted their votes, that the object of the fight was slavery. Many years ago, when General Jackson was President, South Carolina did nearly rebel (she never was near separating) about a tariff; but no other State abetted her, and a strong adverse demonstration from Virginia brought the matter to a close. Yet the tariff of that day was rigidly protective. Compared with that, the one in force at the time of the secession was a free-trade tariff: This latter was the result of several successive modifications in the direction of freedom; and its principle was not protection for protection, but as much of it only as might incidentally result from duties imposed for revenue. Even the Morrill tariff (which never could have been passed but for the Southern secession) is stated by the high authority of Mr. H. C. Carey to be considerably more liberal than the reformed French tariff under Mr. Cobden's treaty; insomuch that he, a Protectionist, would be glad to exchange his own protective tariff for Louis Napoleon's free-trade one. But why discuss, on probable evidence, notorious facts? The world knows what the question between the North and South has been for many years, and still is. Slavery alone was thought of, alone talked of. Slavery was battled for and against, on the floor of Congress and in the plains of Kansas; on the slavery question exclusively was the party constituted which now rules the United States: on slavery Fremont was rejected, on slavery Lincoln was elected; the South separated on slavery, and proclaimed slavery as the one cause of separation.

The communist philosopher Karl Marx also saw slavery as the major cause of the war. Marx wrote extensively in the British press and served as a London correspondent for several North American newspapers including Horace Greeley's New York Tribune. Marx reacted to those who blamed the war on the Morrill Tariff and argued instead that slavery had induced secession and that the tariff was just a pretext. In October 1861, he wrote:

Naturally, in America everyone knew that from 1846 to 1861 a free trade system prevailed, and that Representative Morrill carried his protectionist tariff through Congress only in 1861, after the rebellion had already broken out. Secession, therefore, did not take place because the Morrill tariff had gone through Congress, but, at most, the Morrill tariff went through Congress because secession had taken place.[21]

Rationale

[edit]According to the historian Heather Cox Richardson, Morrill intended to offer protection to both the usual manufacturing recipients and a broad group of agricultural interests. The purpose was to appease interests beyond the Northeast, which traditionally supported protection. For the first time, protection was extended to every major farm product:

Planning to distribute the benefits of a tariff to all sectors of the economy, and also hoping to broaden support for his party, Morrill rejected the traditional system of protection by proposing tariff duties on agricultural, mining, and fishing products, as well as on manufactures. Sugar, wool, flaxseed, hides, beef, pork, corn, grain, hemp, wool, and minerals would all be protected by the Morrill Tariff. The duty on sugar might well be expected to appease Southerners opposed to tariffs, and, notably, wool and flaxseed production were growing industries in the West. The new tariff bill also would protect coal, lead, copper, zinc, and other minerals, all of which the new northwestern states were beginning to produce. The Eastern fishing industry would receive a duty on dried, pickled, and salted fish. "In adjusting the details of a tariff," Morrill explained with a rhetorical flourish in his introduction of the bill, "I would treat agriculture, manufactures, mining, and commerce, as I would our whole people—as members of one family, all entitled to equal favor, and no one to be made the beast of burden to carry the packs of others."[22]

According to Taussig, "Morrill and the other supporters of the act of 1861 declared that their intention was simply to restore the rates of 1846." However, he also gives reason to suspect that the bill's motives were intended to put high rates of protection on iron and wool to attract the West and Pennsylvania:

The important change which they (the sponsors) proposed to make from the provisions of the tariff of 1846 was to substitute specific for ad-valorem duties. Such a change from ad-valorem to specific duties is in itself by no means objectionable; but it has usually been made a pretext on the part of protectionists for a considerable increase in the actual duties paid. When protectionists make a change of this kind, they almost invariably make the specific duties higher than the ad-valorem duties for which they are supposed to be an equivalent.... The Morrill tariff formed no exception to the usual course of things in this respect. The specific duties which it established were in many cases considerably above the ad-valorem duties of 1846. The most important direct changes made by the act of 1861 were in the increased duties on iron and on wool, by which it was hoped to attach to the Republican party Pennsylvania and some of the Western States"[23]

Henry C. Carey, who assisted Morrill in drafting the bill and was one of its most vocal supporters, strongly emphasized its importance to the Republican Party in his January 2, 1861 letter to Lincoln: "the success of your administration is wholly dependent upon the passage of the Morrill bill at the present session." According to Carey:

With it, the people will be relieved — your term will commence with a rising wave of prosperity — the Treasury will be filled and the party that elected you will be increased and strengthened. Without it, there will be much suffering among the people — much dissatisfaction with their duties — much borrowing on the part of the Government — & very much trouble among the Republican Party when the people shall come to vote two years hence. There is but one way to make the Party a permanent one, & that is, by the prompt repudiation to the free trade system.

Representative John Sherman later wrote:

The Morrill tariff bill came nearer than any other to meeting the double requirement of providing ample revenue for the support of the government and of rendering the proper protection to home industries. No national taxes, except duties on imported goods, were imposed at the time of its passage. The Civil War changed all this, reducing importations and adding tenfold to the revenue required. The government was justified in increasing existing rates of duty, and in adding to the dutiable list all articles imported, thus including articles of prime necessity and of universal use. In addition to these duties, it was compelled to add taxes on all articles of home production, on incomes not required for the supply of actual wants, and, especially, on articles of doubtful necessity, such as spirits, tobacco and beer. These taxes were absolutely required to meet expenditures for the army and navy, for the interest on the war debts and just pensions to those who were disabled by the war, and to their widows and orphans.[24]

Secession

[edit]Relation to tariff

[edit]While slavery dominated the secession debate in the south,[25] the Morrill tariff provided an issue for secessionist agitation in some southern states. The law's critics compared it to the 1828 Tariff of Abominations, which sparked the Nullification Crisis, but its average rate was significantly lower.

Robert Barnwell Rhett railed against the pending Morrill Tariff before the 1860 South Carolina convention. Rhett included a lengthy attack on tariffs in the Address of South Carolina to Slaveholding States, which the convention adopted on December 25, 1860, to accompany its secession ordinance:

And so with the Southern States, towards the Northern States, in the vital matter of taxation. They are in a minority in Congress. Their representation in Congress, is useless to protect them against unjust taxation; and they are taxed by the people of the North for their benefit, exactly as the people of Great Britain taxed our ancestors in the British parliament for their benefit. For the last forty years, the taxes laid by the Congress of the United States have been laid with a view of subserving the interests of the North. The people of the South have been taxed by duties on imports, not for revenue, but for an object inconsistent with revenue— to promote, by prohibitions, Northern interests in the productions of their mines and manufactures.[26]

The Morrill Tariff played less prominently elsewhere in the South. In some portions of Virginia, secessionists promised a new protective tariff to assist the state's fledgling industries.[27]

In the North, enforcement of the tariff contributed to support for the Union cause by industrialists and merchant interests. The abolitionist Orestes Brownson derisively remarked that "the Morrill Tariff moved them more than the fall of Sumter."[28] In one such example, the New York Times, which had opposed Morrill's bill on free trade grounds, editorialized that the tariff imbalance would bring commercial ruin to the North and urged its suspension until the secession crisis passed: "We have imposed high duties on our commerce at the very moment the seceding states are inviting commerce to their ports by low duties."[29] As secession became more evident and the fledgling Confederacy adopted a much lower tariff, the paper urged military action to enforce the Morrill Tariff in the South.[30]

Historiography

[edit]Historians, James Huston notes, have been baffled by the role of high tariffs in general and have offered multiple conflicting interpretations over the years. (Low tariffs, all historians agree, were noncontroversial and needed to fund the federal government.) One school of thought says the Republicans were the willing tools of would-be monopolists. A second school says the Republicans truly believed that tariffs would promote nationalism and prosperity for everyone along with balanced growth in every region, as opposed to growth only in the cotton South. A third school emphasizes the undeniable importance of the tariff in cementing party loyalty, especially in industrial states. Another approach emphasizes that factory workers were eager for high tariffs to protect their high wages from European competition.[31]

Charles A. Beard argued in the 1920s that very long-term economic issues were critical, with the pro-tariff industrial Northeast forming a coalition with the anti-tariff agrarian Midwest against the plantation South.

According to Luthin in the 1940s, "Historians are not unanimous as to the relative importance which Southern fear and hatred of a high tariff had in causing the secession of the slave states."[32] However, none of the statesmen seeking a compromise in 1860–61 to avert the war ever suggested the tariff might be either the key to a solution or a cause of the secession.[33]

In the 1950s, historians began to move away from the Beard thesis of economic causality. In its place, historians, led by Richard Hofstadter, began to emphasize the social causes of the war as centered on the issue of slavery.

The Beard thesis has enjoyed a recent revival among economists, pro-Confederate historians, and neo-Beardian scholars. A 2002 study by economists Robert McGuire and T. Norman Van Cott concluded:

A de facto constitutional mandate that tariffs lie on the lower end of the Laffer relationship means that the Confederacy went beyond simply observing that a given tax revenue is obtainable with a "high" and "low" tax rate, a la Alexander Hamilton and others. Indeed, the constitutional action suggests that the tariff issue may in fact have been even more important in the North–South tensions that led to the Civil War than many economists and historians currently believe.

Rather than contributing to secession, Marc-William Palen notes how the tariff was passed through Congress only by the secession of Southern states. Thus, secession itself allowed for the bill's passage, rather than the other way around.[34]

Allan Nevins and James M. McPherson downplay the significance of the tariff; argue that it was peripheral to the issue of slavery; and note that slavery dominated the secessionist declarations, speeches, and pamphlets. Nevins also points to the argument of Alexander Stephens, who disputed Toombs's claims about the severity of the Morrill Tariff. Though initially opposed to secession, Stephens would later cite slavery as the "cornerstone" for his support of secession.[35]

Notes

[edit]- ^ The American Presidency Project. "Political Party Platforms". Archived from the original on 2014-06-04. Retrieved 26 February 2016.

- ^ Coy F. Cross II (2012). Justin Smith Morrill: Father of the Land-Grant Colleges. MSU Press. p. 45. ISBN 9780870139055.

- ^ Kenneth M. Stampp, America in 1857: A Nation on the Brink 1990 p. 19.

- ^ "TO PASS H.R. 338. (p. 2056). – House Vote #151 – May 10, 1860".

- ^ Congressional Globe, 36th Congress, 1st Session, p. 2056

- ^ Allan Nevins, Ordeal of the Union; Vol. IV: The Emergence of Lincoln: Prologue to Civil War, 1859–1861 (1950).

- ^ "Tariffs, Government Policy, and Secession". 25 January 2011.

- ^ Luthin, p. 622

- ^ Jane Flaherty, "'The Exhausted Condition of the Treasury' on the Eve of the Civil War," Civil War History (2009) Volume: 55#2 pp 244 ff. The historian Bray Hammond emphasizes the Treasury's "empty purse." Bray Hammond, Sovereignty and the Empty Purse: Banks and Politics in the Civil War (1970)

- ^ "To Pass H.R. 338. (P. 1065-2). – Senate Vote #512 – Feb 20, 1861".

- ^ Taussig wrote, "It is clear that the Morrill tariff was carried in the House before any serious expectation of war was entertained; and it was accepted by the Senate in the session of 1861 without material change. It therefore forms no part of the financial legislation of the war, which gave rise in time to a series of measures that entirely superseded the Morrill tariff." The Tariff History of the United States

- ^ Taussig

- ^ U.S. Tariff Rates – Ratio of Import Duties to Values: 1821-1996

- ^ Richardson, 100, 113

- ^ Jerry W. Markham, A financial history of the United States (2001) vol 3 p 220

- ^ Marc-William Palen, "The Civil War's Forgotten Transatlantic Tariff Debate and the Confederacy's Free Trade Diplomacy," Journal of the Civil War Era 3: 1 (March 2013): 35–61

- ^ Richardson p. 114

- ^ Johnson p. 14

- ^ Unlike the situation with Household Words, no ledger survives giving the authorship of each article in All the Year Round but Dickens scholar Ella Ann Oppenlander has attempted to provide a list in a work that is not easily procured, Dickens's All the Year Round: Descriptive Index and Contributor List (1984). The article that the above quote is from is widely regarded by scholars as a follow-up to an article from a week earlier, American Disunion. Graham Storey in The Letters of Charles Dickens attributes both articles to staff writer Henry Morley, based on a letter by Dickens stating that "you say nothing of the book on the American Union in Morley's hands. I hope and trust his article will be ready for the next No. made up. There will not be the least objection to having American papers in it." He afterwards wrote, "It is scarcely possible to make less of Mr. Spence's book, than Morley has done." Dickens micromanaged the magazine and so none dispute that Dickens must have generally endorsed the ideas in the articles.

- ^ "The Contest in America, by John Stuart Mill".

- ^ Biographies

- ^ Richardson p. 105

- ^ Taussig p. 99

- ^ John Sherman's Recollections of Forty Years in the House, Senate, and Cabinet: An Autobiography 1895.

- ^ Dew p. 12. For example, Dew notes that in South Carolina the Declaration of Causes adopted by the secession convention "focused primarily on the Northern embrace of antislavery principles and the evil designs of the newly triumphant Republican Party" and Georgia's convention was "equally outspoken on the subject of slavery."

- ^ Address of South Carolina to Slaveholding States by Convention of South Carolina

- ^ Carlander and Majewski, 2003

- ^ "Emancipation and Colonization," Brownson's Quarterly Review, April 1862

- ^ "The Tariff and Secession", The New York Times, March 26, 1861

- ^ "The Great Question", The New York Times, March 30, 1861

- ^ James L. Huston, "A Political Response to Industrialism: The Republican Embrace of Protectionist Labor Doctrines," Journal of American History, June 1983, Vol. 70 Issue 1, pp 35–57

- ^ Luthin, p. 626

- ^ Robert G. Gunderson, Old Gentlemen's Convention: The Washington Peace Conference of 1861 (1981)

- ^ Marc-William Palen, "The Great Civil War Lie," New York Times, June 5, 2013

- ^ "Teaching American History library". Archived from the original on 2007-11-17. Retrieved 2005-09-14.

References

[edit]Bibliography

[edit]- Charles and Mary Beard. The Rise of American Civilization (1928)

- Paul Bairoch, (1993), Economics and World History: Myths and Paradoxes

- Jay Carlander and John Majewski. "Imagining 'A Great Manufacturing Empire': Virginia and the Possibilities of a Confederate Tariff," Civil War History Vol. 49, 2003

- Dew, Charles B. Apostles of Disunion: Southern Secession Commissioners and the Causes of the Civil War. (2001) ISBN 0-8139-2036-1

- William Freehling and Craig Simpson, editors. Secession Debated: Georgia's Showdown in 1860. (1992) ISBN 0-19-507945-0.

- Richard Hofstadter, The Progressive Historians—Turner, Beard, Parrington (1968)

- Richard Hofstadter, "The Tariff Issue on the Eve of the Civil War" in American Historical Review, Vol. 44, No. 1 (Oct., 1938), pp. 50–55 in JSTOR

- James L. Huston, "A Political Response to Industrialism: The Republican Embrace of Protectionist Labor Doctrines," Journal of American History, June 1983, Vol. 70 Issue 1, pp 35–57 in JSTOR

- Willis Fletcher Johnson; America's Foreign Relations. Volume: 2 (1916).

- Reinhard H. Luthin, "Abraham Lincoln and the Tariff" in The American Historical Review Vol. 49, No. 4 (Jul., 1944), pp. 609–629

- Robert McGuire and T. Norman Van Cott. "The Confederate constitution, tariffs, and the Laffer relationship", Economic Inquiry, Vol. 40, No. 3 – 2002

- James M. McPherson. Battle Cry of Freedom: The Civil War Era (1988)

- Phillip W. Magness. "Morrill and the Missing Industries: Strategic Lobbying Behavior and the Tariff, 1858–1861" Journal of the Early Republic Vol. 29-2 (2009) in Project MUSE

- Charles R. Morris. The Tycoons: How Andrew Carnegie, John D. Rockefeller, Jay Gould, and J. P. Morgan Invented the American Supereconomy (2005)

- Allan Nevins. Ordeal of the Union, an 8-volume set (1947–1971), Vol. 4 "Prologue to Civil War, 1859–1861"

- Magness, Phillip W. "Abraham Lincoln's Swing State Strategy: Tariff Surrogates and the Pennsylvania Election of 1860." Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography 143.1 (2019): 5–32. online

- Marc-William Palen. The "Conspiracy" of Free Trade: The Anglo-American Struggle over Empire and Economic Globalization, 1846–1896 (2016)

- Marc-William Palen, "Debunking the Civil War Tariff Myth," Imperial & Global Forum, March 2, 2015

- Marc-William Palen. "The Great Civil War Lie," New York Times, June 5, 2013

- Marc-William Palen. "The Civil War's Forgotten Transatlantic Tariff Debate and the Confederacy's Free Trade Diplomacy," Journal of the Civil War Era 3: 1 (March 2013): 35–61

- Marc-William Palen, "Debating the Causes of the Civil War," Not Even Past: A Project of the University of Texas History Department (Retrieved November 3, 2011)

- Daniel Peart. 2018. Lobbyists and the Making of U.S. Trade Policy, 1816–1861. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press.

- David Potter, The impending crisis, 1848–1861 (1976)

- James Ford Rhodes. History of the Civil War, 1861–1865 (1918)

- Heather Cox Richardson, The Greatest Nation of the Earth: Republican Economic Policies during the Civil War (Cambridge: Harvard University Press. 1997)

- Paul Studenski and Herman E. Krooss. Financial History of the United States: Fiscal, Monetary, Banking, and Tariff, Including Financial Administration and State and Local Finance (1952)

- Frank Taussig, The Tariff History of the United States (1911)

- The Congressional Globe at the Library of Congress

- The Abraham Lincoln Papers at the Library of Congress