Rembrandt

Rembrandt | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | Rembrandt Harmenszoon van Rijn 15 July 1606[1] |

| Died | 4 October 1669 (aged 63) Amsterdam, Dutch Republic |

| Education | Jacob van Swanenburg Pieter Lastman |

| Known for | Painting, printmaking, drawing |

| Notable work | Self-portraits The Anatomy Lesson of Dr. Nicolaes Tulp (1632) Belshazzar's Feast The Night Watch (1642) The Hundred Guilder Print (etching, c. 1647–1649) Bathsheba at Her Bath (1654) Syndics of the Drapers' Guild (1662) |

| Movement | Dutch Golden Age Baroque |

| Spouse | |

| Children | 2, including Titus |

| Signature | |

| |

Rembrandt Harmenszoon van Rijn (/ˈrɛmbrænt, ˈrɛmbrɑːnt/,[2] Dutch: [ˈrɛmbrɑnt ˈɦɑrmə(n)ˌsoːɱ vɑn ˈrɛin] ; 15 July 1606[1] – 4 October 1669), usually simply known as Rembrandt, was a Dutch Golden Age painter, printmaker, and draughtsman. He is generally considered one of the greatest visual artists in the history of art.[3] It is estimated Rembrandt produced a total of about three hundred paintings, three hundred etchings, and two thousand drawings.

Unlike most Dutch painters of the 17th century, Rembrandt's works depict a wide range of styles and subject matter, from portraits and self-portraits to landscapes, genre scenes, allegorical and historical scenes, biblical and mythological themes and animal studies. His contributions to art came in a period that historians call the Dutch Golden Age.

Rembrandt never went abroad but was considerably influenced by the work of the Italian Old Masters and Dutch and Flemish artists who had studied in Italy. After he achieved youthful success as a portrait painter, Rembrandt's later years were marked by personal tragedy and financial hardships. Yet his etchings and paintings were popular throughout his lifetime, his reputation as an artist remained high,[4] and for twenty years he taught many important Dutch painters.[5] Rembrandt's portraits of his contemporaries, self-portraits and illustrations of scenes from the Bible are regarded as his greatest creative triumphs. His approximately 40 self-portraits form an intimate autobiography.[3][6]

Early life and education

[edit]

Rembrandt[a] Harmenszoon van Rijn was born on 15 July 1606 in Leiden,[1] in the Dutch Republic, now the Netherlands. He was the ninth child born to Harmen Gerritszoon van Rijn and Neeltgen Willemsdochter van Zuijtbrouck.[8] His family was quite well-to-do; his father was a miller and his mother was a baker's daughter. His mother was Catholic, and his father belonged to the Dutch Reformed Church. Religion is a central theme in Rembrandt's works and the religiously fraught period in which he lived makes his faith a matter of interest.

As a boy, he attended a Latin school. In 1620, he was enrolled at the University of Leiden, although he had a greater inclination towards painting and was soon apprenticed to Jacob van Swanenburg, with whom he spent three years.[9] After a brief but important apprenticeship of six months with the history painter Pieter Lastman in Amsterdam, Rembrandt stayed a few months with Jacob Pynas in 1625, though Simon van Leeuwen claimed that Rembrandt was taught by Joris van Schooten and then started his own workshop.[9][10]

Career

[edit]

In 1625, Rembrandt opened a studio in Leiden, which he shared with friend and colleague Jan Lievens. In 1627, Rembrandt began to accept students, among them Gerrit Dou and Isaac de Jouderville.[11] Joan Huydecoper is mentioned as the first buyer of a Rembrandt painting in 1628.[12] In 1629, Rembrandt was discovered by the statesman Constantijn Huygens who procured for Rembrandt important commissions from the court of The Hague. As a result of this connection, Prince Frederik Hendrik continued to purchase paintings from Rembrandt.[13]

At the end of 1631, Rembrandt moved to Amsterdam, a city rapidly expanding as the business and trade capital. He began to practice as a professional portraitist for the first time, with great success. He initially stayed with an art dealer, Hendrick van Uylenburgh, and in 1634, married Hendrick's cousin, Saskia van Uylenburgh.[14][15] Saskia came from a respected family: her father Rombertus was a lawyer and had been burgomaster (mayor) of Leeuwarden. The couple married in the local church of St. Annaparochie without the presence of Rembrandt's relatives.[16] In the same year, Rembrandt became a citizen of Amsterdam and a member of the local guild of painters. He also acquired a number of students, among them Ferdinand Bol and Govert Flinck.[17]

In 1635, Rembrandt and Saskia rented a fashionable lodging with a view of the river Amstel.[18] In 1637, Rembrandt moved upriver to Vlooienburg, in a building on the previous site of the current Stopera.[19] In May 1639 they moved to a recently modernized house in the upscale 'Breestraat' with artists and art dealers; Nicolaes Pickenoy, a portrait painter, was his neighbor. The mortgage to finance the 13,000 guilder purchase would be a cause for later financial difficulties.[b][17] The neighborhood sheltered many immigrants and was becoming the Jewish quarter. It was there that Rembrandt frequently sought his Jewish neighbors to model for his Old Testament scenes.[22] One of the great patrons at the early stages of his career was Amsterdam statesman Andries de Graeff.[23][24]

Although they were by now affluent, the couple suffered several personal setbacks; three children died within weeks of their births.[c][d] Only their fourth child, Titus, who was born in 1641, survived into adulthood. Saskia died in 1642, probably from tuberculosis. Rembrandt's drawings of her on her sick and death bed are among his most moving works.[26][18] After Saskia's illness, the widow Geertje Dircx was hired as Titus' caretaker and dry nurse; at some time, she also became Rembrandt's lover. In May 1649 she left and charged Rembrandt with breach of promise and asked to be awarded alimony.[17] Rembrandt tried to settle the matter amicably, but to pay her lawyer she pawned the diamond ring he had given her that once belonged to Saskia. On 14 October they came to an agreement; the court particularly stated that Rembrandt had to pay a yearly maintenance allowance, provided that Titus remained her only heir and she sold none of Rembrandt's possessions.[27][28] As Dircx broke her promise, Rembrandt and members of Dircx's own family had her committed to a women's house of correction at Gouda in August 1650. Rembrandt also took measures to ensure she stay in the house of correction for as long as possible.[29] Rembrandt paid for the costs.[30][e]

In early 1649, Rembrandt began a relationship with the 23-year-old Hendrickje Stoffels, who had initially been his maid. She may have been the cause of Geertje's leaving. In that year he made no (dated) paintings or etchings at all.[31] In 1654 Rembrandt produced a controversial nude Bathsheba at Her Bath. In June Hendrickje received three summonses from the Reformed Church to answer the charge "that she had committed the acts of a whore with Rembrandt the painter". In July she admitted her guilt and was banned from receiving communion.[32] Rembrandt was not summoned to appear for the Church council.[33] In October they had a daughter, Cornelia. Had he remarried he would have lost access to a trust set up for Titus in Saskia's will.[26]

Insolvency

[edit]

Rembrandt, despite his artistic success, found himself in financial turmoil. His penchant for acquiring art, prints, and rare items led him to live beyond his means. In January 1653 the sale of the property formally was finalized but Rembrandt still had to cover half of the remaining mortgage. Creditors began pressing for installments but Rembrandt, facing financial strain, sought a postponement. The house required repairs prompting Rembrandt to borrow money from friends, including Jan Six.[34][f]

In November 1655, amid a year overshadowed by plague and the drafting of wills, Rembrandt's 14-year-old son Titus took a significant step by drafting a will that designated his father as the sole heir, effectively sidelining his mother's family.[37][38] In December Rembrandt orchestrated a sale of his paintings, yet the earnings failed to meet expectations.[39] This tumultuous period deeply impacted the art industry, prompting Rembrandt to seek a high court arrangement known as cessio bonorum.[40] Despite the financial difficulties, Rembrandt's bankruptcy wasn't forced.[39][41] In July 1656, he declared his insolvency, taking stock and willingly surrendered his assets.[42] Notably, he had already transferred the house to his son.[21] Both the authorities and his creditors showed leniency, granting him ample time to settle his debts. Jacob J. Hinlopen allegedly played a role.[43]

In November 1657 another auction was held to sell his paintings, as well as a substantial number of etching plates and drawings, some by renowned artists such as Raphael, Mantegna and Giorgione.[g] Remarkably, Rembrandt was permitted to retain his tools as a means of generating income.[21] Rembrandt lost the guardianship of his son and thus control over his actions. A new guardian, Louis Crayers, claimed the house in settlement of Titus's debt.[44]

The sale list comprising 363 items offers insight into Rembrandt's diverse collections, which, encompassed Old Master paintings, drawings, Roman emperors busts, Greek philosophers statues, books (a bible), two globes, bonnets, armor, and various objects from Asia (chinaware), as well as a collections of natural history specimens (two lion skins, a bird-of-paradise, corals and minerals).[45] Unfortunately, the prices realized in the sale were disappointing.[46]

By February 1658, Rembrandt' house was sold at a foreclosure auction, and the family moved to more modest lodgings at Rozengracht.[47] In 1660, he finished Ahasuerus and Haman at the feast of Esther which he sold to Jan J. Hinlopen.[48] Early December 1660, the sale of the house was finalized but the proceeds went directly to Titus' guardian.[49][50]

Two weeks later, Hendrickje and Titus established a dummy corporation as art dealers, allowing Rembrandt, who had board and lodging, to continue his artistic pursuits.[51][52] In 1661, they secured a contract for a major project at the newly completed town hall. The resulting work, The Conspiracy of Claudius Civilis, was rejected by the mayors and returned to the painter within a few weeks; the surviving fragment (in Stockholm) is only a quarter of the original.[53]

Despite these setbacks, Rembrandt continued to receive significant portrait commissions and completed notable works, such as the Sampling Officials in 1662.[54] It remains a challenge to gauge Rembrandt's wealth accurately as he may have overestimated the value of his art collection.[42] Nonetheless, half of his assets were earmarked for Titus' inheritance.[55]

In March 1663, with Hendrickje's illness, Titus assumed a more prominent role. Isaac van Hertsbeeck, Rembrandt's primary creditor, went to the High Court and contested Titus' priority for payment, leading to legal battles that Titus ultimately won in 1665 when he came of age.[56][57][58] During this time, Rembrandt worked on notable pieces like the Jewish Bride and his final self-portraits but struggled with rent arrears.[59] Notably, Cosimo III de' Medici, Grand Duke of Tuscany, visited Rembrandt twice, and returned to Florence with one of the self-portraits.[60]

Rembrandt outlived both Hendrickje and Titus; he died on Friday 4 October 1669 and was buried four days later in a rented grave in the Westerkerk.[61] His illegitimate child, Cornelia (1654–1684), eventually moved to Batavia in 1670 accompanied by an obscure painter and her mother's inheritance.[62] Titus' considerable inheritance passed to his only child, Titia (1669-1715) who married her cousin and lived at Blauwburgwal.[63] Rembrandt's life was marked by more than just artistic achievements; he navigated numerous legal and financial challenges, leaving a complex legacy.[64][65]

Works

[edit]

In a letter to Huygens, Rembrandt offered the only surviving explanation of what he sought to achieve through his art, writing that, "the greatest and most natural movement", translated from de meeste en de natuurlijkste beweegelijkheid. The word "beweegelijkheid" translates to "emotion" or "motive". Whether this refers to objectives, material, or something else, is not known but critics have drawn particular attention to the way Rembrandt seamlessly melded the earthly and spiritual.[66]

Earlier 20th century connoisseurs claimed Rembrandt had produced well over 600 paintings,[67] nearly 400 etchings and 2,000 drawings.[68] More recent scholarship, from the 1960s to the present day (led by the Rembrandt Research Project), often controversially, has winnowed his oeuvre to nearer 300 paintings.[h] His prints, traditionally all called etchings, although many are produced in whole or part by engraving and sometimes drypoint, have a much more stable total of slightly under 300.[i] It is likely Rembrandt made many more drawings in his lifetime than 2,000 but those extant are more rare than presumed.[j] Two experts claim that the number of drawings whose autograph status can be regarded as effectively "certain" is no higher than about 75, although this is disputed. The list was to be unveiled at a scholarly meeting in February 2010.[71]

At one time, approximately 90 paintings were counted as Rembrandt self-portraits but it is now known that he had his students copy his own self-portraits as part of their training. Modern scholarship has reduced the autograph count to over forty paintings, as well as a few drawings and thirty-one etchings, which include many of the most remarkable images of the group.[72] Some show him posing in quasi-historical fancy dress, or pulling faces at himself. His oil paintings trace the progress from an uncertain young man, through the dapper and very successful portrait-painter of the 1630s, to the troubled but massively powerful portraits of his old age. Together they give a remarkably clear picture of the man, his appearance and his psychological make-up, as revealed by his richly weathered face.[k]

In his portraits and self-portraits, he angles the sitter's face in such a way that the ridge of the nose nearly always forms the line of demarcation between brightly illuminated and shadowy areas. A Rembrandt face is a face partially eclipsed; and the nose, bright and obvious, thrusting into the riddle of halftones, serves to focus the viewer's attention upon, and to dramatize, the division between a flood of light—an overwhelming clarity—and a brooding duskiness.[73]

In a number of biblical works, including The Raising of the Cross, Joseph Telling His Dreams, and The Stoning of Saint Stephen, Rembrandt painted himself as a character in the crowd. Durham suggests that this was because the Bible was for Rembrandt "a kind of diary, an account of moments in his own life".[74]

Among the more prominent characteristics of Rembrandt's work are his use of chiaroscuro, the theatrical employment of light and shadow derived from Caravaggio, or, more likely, from the Dutch Caravaggisti but adapted for very personal means.[75] Also notable are his dramatic and lively presentation of subjects, devoid of the rigid formality that his contemporaries often displayed, and a deeply felt compassion for mankind, irrespective of wealth and age. His immediate family—his wife Saskia, his son Titus and his common-law wife Hendrickje—often figured prominently in his paintings, many of which had mythical, biblical or historical themes.

Periods, themes and styles

[edit]

Throughout his career, Rembrandt took as his primary subjects the themes of portraiture, landscape and narrative painting. For the last, he was especially praised by his contemporaries, who extolled him as a masterly interpreter of biblical stories for his skill in representing emotions and attention to detail.[78] Stylistically, his paintings progressed from the early "smooth" manner, characterized by fine technique in the portrayal of illusionistic form, to the late "rough" treatment of richly variegated paint surfaces, which allowed for an illusionism of form suggested by the tactile quality of the paint itself. Rembrandt must have realized that if he kept the paint deliberately loose and "paint-like" on some parts of the canvas, the perception of space became much greater.[79]

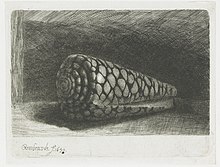

A parallel development may be seen in Rembrandt's skill as a printmaker. In the etchings of his maturity, particularly from the late 1640s onward, the freedom and breadth of his drawings and paintings found expression in the print medium as well. The works encompass a wide range of subject matter and technique, sometimes leaving large areas of white paper to suggest space, at other times employing complex webs of line to produce rich dark tones.[80]

Lastman's influence on Rembrandt was most prominent during his period in Leiden from 1625 to 1631.[81] Paintings were rather small but rich in details (for example, in costumes and jewelry). Religious and allegorical themes were favored, as were tronies.[81] In 1626 Rembrandt produced his first etchings, the wide dissemination of which would largely account for his international fame.[81] In 1629, he completed Judas Repentant, Returning the Pieces of Silver and The Artist in His Studio, works that evidence his interest in the handling of light and variety of paint application and constitute the first major progress in his development as a painter.[82]

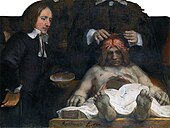

During his early years in Amsterdam (1632–1636), Rembrandt began to paint dramatic biblical and mythological scenes in high contrast and of large format (The Blinding of Samson, 1636, Belshazzar's Feast, c. 1635 Danaë, 1636 but reworked later), seeking to emulate the baroque style of Rubens.[83] With the occasional help of assistants in Uylenburgh's workshop, he painted numerous portrait commissions both small (Jacob de Gheyn III) and large (Portrait of the Shipbuilder Jan Rijcksen and his Wife, 1633, Anatomy Lesson of Dr. Nicolaes Tulp, 1632).[84]

By the late 1630s, Rembrandt had produced a few paintings and many etchings of landscapes. Often these landscapes highlighted natural drama, featuring uprooted trees and ominous skies (Cottages before a Stormy Sky, c. 1641; The Three Trees, 1643). From 1640 his work became less exuberant and more sober in tone, possibly reflecting personal tragedy. Biblical scenes were now derived more often from the New Testament than the Old Testament, as had been the case before. In 1642 he painted The Night Watch, the most substantial of the important group portrait commissions which he received in this period, and through which he sought to find solutions to compositional and narrative problems that had been attempted in previous works.[85]

In the decade following the Night Watch, Rembrandt's paintings varied greatly in size, subject, and style. The previous tendency to create dramatic effects primarily by strong contrasts of light and shadow gave way to the use of frontal lighting and larger and more saturated areas of color. Simultaneously, figures came to be placed parallel to the picture plane. These changes can be seen as a move toward a classical mode of composition and, considering the more expressive use of brushwork as well, may indicate a familiarity with Venetian art (Susanna and the Elders, 1637–47).[86] At the same time, there was a marked decrease in painted works in favor of etchings and drawings of landscapes.[87] In these graphic works natural drama eventually made way for quiet Dutch rural scenes.

In the 1650s, Rembrandt's style changed again. Colors became richer and brush strokes more pronounced. With these changes, Rembrandt distanced himself from earlier work and current fashion, which increasingly inclined toward fine, detailed works. His use of light becomes more jagged and harsh, and shine becomes almost nonexistent. His singular approach to paint application may have been suggested in part by familiarity with the work of Titian, and could be seen in the context of the then current discussion of 'finish' and surface quality of paintings. Contemporary accounts sometimes remark disapprovingly of the coarseness of Rembrandt's brushwork, and the artist himself was said to have dissuaded visitors from looking too closely at his paintings.[88] The tactile manipulation of paint may hearken to medieval procedures, when mimetic effects of rendering informed a painting's surface. The result is a richly varied handling of paint, deeply layered and often apparently haphazard, which suggests form and space in both an illusory and highly individual manner.[89]

In later years, biblical themes were often depicted but emphasis shifted from dramatic group scenes to intimate portrait-like figures (James the Apostle, 1661). In his last years, Rembrandt painted his most deeply reflective self-portraits (from 1652 to 1669 he painted fifteen), and several moving images of both men and women (The Jewish Bride, c. 1666)—in love, in life, and before God.[90][91]

Graphic works

[edit]

Rembrandt produced etchings for most of his career, from 1626 to 1660, when he was forced to sell his printing-press and practically abandoned etching. Only the troubled year of 1649 produced no dated work.[92] He took easily to etching and, though he learned to use a burin and partly engraved many plates, the freedom of etching technique was fundamental to his work. He was very closely involved in the whole process of printmaking, and must have printed at least early examples of his etchings himself. At first he used a style based on drawing but soon moved to one based on painting, using a mass of lines and numerous bitings with the acid to achieve different strengths of line. Towards the end of the 1630s, he reacted against this manner and moved to a simpler style, with fewer bitings.[93] He worked on the so-called Hundred Guilder Print in stages throughout the 1640s, and it was the "critical work in the middle of his career", from which his final etching style began to emerge.[94] Although the print only survives in two states, the first very rare, evidence of much reworking can be seen underneath the final print and many drawings survive for elements of it.[95]

In the mature works of the 1650s, Rembrandt was more ready to improvise on the plate and large prints typically survive in several states, up to eleven, often radically changed. He now used hatching to create his dark areas, which often take up much of the plate. He also experimented with the effects of printing on different kinds of paper, including Japanese paper, which he used frequently, and on vellum. He began to use "surface tone", leaving a thin film of ink on parts of the plate instead of wiping it completely clean to print each impression. He made more use of drypoint, exploiting, especially in landscapes, the rich fuzzy burr that this technique gives to the first few impressions.[96]

His prints have similar subjects to his paintings, although the 27 self-portraits are relatively more common, and portraits of other people less so. The landscapes, mostly small, largely set the course for the graphic treatment of landscape until the end of the 19th century. Of the many hundreds of drawings Rembrandt made, only about two hundred have a landscape motif as their subject, and of the approximately three hundred etchings, about thirty show a landscape. As for his painted landscapes, one does not even get beyond eight works.[97] One third of his etchings are of religious subjects, many treated with a homely simplicity, whilst others are his most monumental prints. A few erotic, or just obscene, compositions have no equivalent in his paintings.[98] He owned, until forced to sell it, a magnificent collection of prints by other artists, and many borrowings and influences in his work can be traced to artists as diverse as Mantegna, Raphael, Hercules Seghers, and Giovanni Benedetto Castiglione.

Drawings by Rembrandt and his pupils/followers have been extensively studied by many artists and scholars[l] through the centuries. His original draughtsmanship has been described as an individualistic art style that was very similar to East Asian old masters, most notably Chinese masters:[105][106]

Asian inspiration

[edit]

Rembrandt was interested in Mughal miniatures, especially around the 1650s. He drew versions of some 23 Mughal paintings and may have owned an album of them. These miniatures include paintings of Shah Jahan, Akbar, Jahangir and Dara Shikoh and may have influenced the costumes and other aspects of his works.[107][108][109][110]

The Night Watch

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (July 2024) |

Rembrandt painted The Militia Company of Captain Frans Banning Cocq between 1640 and 1642, and it became his most famous work.[111] This picture was called De Nachtwacht by the Dutch and The Night Watch by Sir Joshua Reynolds because by 1781 the picture was so dimmed and defaced that it was almost indistinguishable, and it looked quite like a night scene. After it was cleaned, it was discovered to represent broad day—a party of 18 musketeers stepping from a gloomy courtyard into the blinding sunlight. For Théophile Thoré it was the prettiest painting in the world.

The piece was commissioned for the new hall of the Kloveniersdoelen, the musketeer branch of the civic militia. Rembrandt departed from convention, which ordered that such genre pieces should be stately and formal, rather a line-up than an action scene. Instead, he showed the militia readying themselves to embark on a mission, though the exact nature of the mission or event is a matter of ongoing debate.

Contrary to what is often said, the work was hailed as a success from the beginning. Parts of the canvas were cut off (approximately 20% from the left-hand side was removed) to make the painting fit its new position when it was moved to the town hall in 1715. In 1817 this large painting was moved to the Trippenhuis. Since 1885 the painting is on display at the Rijksmuseum.[m] In 1940 the painting was moved to Kasteel Radboud; in 1941 to a bunker near Heemskerk; in 1942 to St Pietersberg; in June 1945 it was shipped back to Amsterdam.

Expert assessments

[edit]

In 1968, the Rembrandt Research Project began under the sponsorship of the Netherlands Organization for the Advancement of Scientific Research; it was initially expected to last a highly optimistic ten years. Art historians teamed up with experts from other fields to reassess the authenticity of works attributed to Rembrandt, using all methods available, including state-of-the-art technical diagnostics, and to compile a complete new catalogue raisonné of his paintings. As a result of their findings, many paintings that were previously attributed to Rembrandt have been removed from their list, although others have been added back.[113] Many of those removed are now thought to be the work of his students.

One example of activity is The Polish Rider, now housed in the Frick Collection in New York City. Rembrandt's authorship had been questioned by at least one scholar, Alfred von Wurzbach, at the beginning of the twentieth century but for many decades later most scholars, including the foremost authority writing in English, Julius S. Held, agreed that it was indeed by the master. In the 1980s, however, Dr. Josua Bruyn of the Foundation Rembrandt Research Project cautiously and tentatively attributed the painting to one of Rembrandt's closest and most talented pupils, Willem Drost, about whom little is known. But Bruyn's remained a minority opinion, the suggestion of Drost's authorship is now generally rejected, and the Frick itself never changed its own attribution, the label still reading "Rembrandt" and not "attributed to" or "school of". More recent opinion has shifted even more decisively in favor of the Frick; In his 1999 book Rembrandt's Eyes, Simon Schama and the Rembrandt Project scholar Ernst van de Wetering (Melbourne Symposium, 1997) both argued for attribution to the master. Those few scholars who still question Rembrandt's authorship feel that the execution is uneven and favour different attributions for different parts of the work.[114]

A similar issue was raised by Schama concerning the verification of titles associated with the subject matter depicted in Rembrandt's works. For example, the exact subject being portrayed in Aristotle with a Bust of Homer, recently retitled by curators at the Metropolitan Museum, has been directly challenged by Schama applying the scholarship of Paul Crenshaw.[115] Schama presents a substantial argument that it was the famous ancient Greek painter Apelles who is depicted in contemplation by Rembrandt and not Aristotle.[116]

Another painting, Pilate Washing His Hands, is also of questionable attribution. Critical opinion of this picture has varied since 1905, when Wilhelm von Bode described it as "a somewhat abnormal work" by Rembrandt. Scholars have since dated the painting to the 1660s and assigned it to an anonymous pupil, possibly Aert de Gelder. The composition bears superficial resemblance to mature works by Rembrandt but lacks the master's command of illumination and modeling.[117]

The attribution and re-attribution work is ongoing. In 2005 four oil paintings previously attributed to Rembrandt's students were reclassified as the work of Rembrandt himself: Study of an Old Man in Profile and Study of an Old Man with a Beard from a US private collection, Study of a Weeping Woman, owned by the Detroit Institute of Arts, and Portrait of an Elderly Woman in a White Bonnet, painted in 1640.[118] The Old Man Sitting in a Chair is a further example: in 2014, Professor Ernst van de Wetering offered his view to The Guardian that the demotion of the 1652 painting Old Man Sitting in a Chair "was a vast mistake...it is a most important painting. The painting needs to be seen in terms of Rembrandt's experimentation". This was highlighted much earlier by Nigel Konstam who studied Rembrandt throughout his career.[119]

Rembrandt's own studio practice is a major factor in the difficulty of attribution, since, like many masters before him, he encouraged his students to copy his paintings, sometimes finishing or retouching them to be sold as originals, and sometimes selling them as authorized copies. Additionally, his style proved easy enough for his most talented students to emulate. Further complicating matters is the uneven quality of some of Rembrandt's own work, and his frequent stylistic evolutions and experiments.[120] As well, there were later imitations of his work, and restorations which so seriously damaged the original works that they are no longer recognizable.[121]

Painting materials

[edit]

Technical investigation of Rembrandt's paintings in the possession of the Gemäldegalerie Alte Meister[122] and in the Gemäldegalerie Alte Meister (Kassel)[123] was conducted by Hermann Kühn in 1977. The pigment analyses of some thirty paintings have shown that Rembrandt's palette consisted of the following pigments: lead white, various ochres, Vandyke brown, bone black, charcoal black, lamp black, vermilion, madder lake, azurite, ultramarine, yellow lake and lead-tin-yellow. Synthetic orpiment was shown in the shadows of the sleeve of the jewish groom. This toxic arsenic yellow was rarely used in oil painting.[124] One painting (Saskia van Uylenburgh as Flora)[125] reportedly contains gamboge. Rembrandt very rarely used pure blue or green colors, the most pronounced exception being Belshazzar's Feast[126][127] in the National Gallery in London. The book by Bomford[126] describes more recent technical investigations and pigment analyses of Rembrandt's paintings predominantly in the National Gallery in London. The entire array of pigments employed by Rembrandt can be found at ColourLex.[128] The best source for technical information on Rembrandt's paintings on the web is the Rembrandt Database containing all works of Rembrandt with detailed investigative reports, infrared and radiography images and other scientific details.[129]

Name and signature

[edit]

"Rembrandt" is a modification of the spelling of the artist's first name that he introduced in 1633. "Harmenszoon" indicates that his father's name is Harmen. "van Rijn" indicates that his family lived near the Rhine.[130]

Rembrandt's earliest signatures (c. 1625) consisted of an initial "R", or the monogram "RH" (for Rembrant Harmenszoon), and starting in 1629, "RHL" (the "L" stood, presumably, for Leiden). In 1632, he used this monogram early in the year, then added his family name to it, "RHL-van Rijn" but replaced this form in that same year and began using his first name alone with its original spelling, "Rembrant". In 1633 he added a "d", and maintained this form consistently from then on, proving that this minor change had a meaning for him (whatever it might have been). This change is purely visual; it does not change the way his name is pronounced. Curiously enough, despite the large number of paintings and etchings signed with this modified first name, most of the documents that mentioned him during his lifetime retained the original "Rembrant" spelling. (Note: the rough chronology of signature forms above applies to the paintings, and to a lesser degree to the etchings; from 1632, presumably, there is only one etching signed "RHL-v. Rijn", the large-format "Raising of Lazarus", B 73).[131] His practice of signing his work with his first name, later followed by Vincent van Gogh, was probably inspired by Raphael, Leonardo da Vinci and Michelangelo who, then as now, were referred to by their first names alone.[132]

Workshop

[edit]

Rembrandt ran a large workshop and had many pupils. The list of Rembrandt pupils from his period in Leiden as well as his time in Amsterdam is quite long, mostly because his influence on painters around him was so great that it is difficult to tell whether someone worked for him in his studio or just copied his style for patrons eager to acquire a Rembrandt. A partial list should include[133] Ferdinand Bol, Adriaen Brouwer, Gerrit Dou, Willem Drost, Heiman Dullaart, Gerbrand van den Eeckhout, Carel Fabritius, Govert Flinck, Hendrick Fromantiou, Aert de Gelder, Samuel Dirksz van Hoogstraten, Abraham Janssens, Godfrey Kneller, Philip de Koninck, Jacob Levecq, Nicolaes Maes, Jürgen Ovens, Christopher Paudiß, Willem de Poorter, Jan Victors, and Willem van der Vliet.

Museum collections

[edit]

The largest collections of Rembrandt's work are in the United States in the Metropolitan Museum of Art (mostly portraits) and the Frick Collection in New York City, the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C., Museum of Fine Arts in Boston, and J. Paul Getty Museum in Los Angeles, in total 86 paintings.[134] Other large groups are in Germany, with 69 paintings, at the Gemäldegalerie in Berlin, Gemäldegalerie Alte Meister in Dresden, and Schloss Wilhelmshöhe in Kassel, and elsewhere. The UK has a total of 51, especially in the National Gallery and Royal Collection. There are 49 in the Netherlands, many in the Rijksmuseum, which has The Night Watch and The Jewish Bride, and the Mauritshuis in The Hague.[135] Others can be found in The Louvre, the Hermitage Museum, and Nationalmuseum, Stockholm. The Royal Castle in Warsaw displays two paintings by Rembrandt.[136]

The largest collections of drawings are in the older large museums such as the Rijksmuseum, Louvre and British Museum. All major print rooms have large collections of Rembrandt prints, although as some exist in only a single impression, no collection is complete. The degree to which these collections are displayed to the public or can easily be viewed by them in the print room, varies greatly.

The Rembrandt House Museum has fittings and furniture that are mostly not original but period pieces comparable to those Rembrandt might have had, and those in the many drawings and etchings set in the house, and contemporary paintings reflecting Rembrandt's use of the house for art dealing. His printmaking studio has been set up with a printing press, where replica prints are printed. The museum has a few early Rembrandt paintings, many loaned but an important collection of his prints, a good selection of which are on rotating display.

Works about Rembrandt

[edit]Literary works (e.g. poetry and fiction)

[edit]- To the Picture of Rembrandt, a Russian-language poem by Mikhail Lermontov, 1830

- Gaspard de la nuit: Fantaisies à la manière de Rembrandt et de Callot, a series of French-language poems by Aloysius Bertrand, 1842

- Picture This, a novel by Joseph Heller, 1988

- Moi, la Putain de Rembrandt, a French-language novel by Sylvie Matton, 1998

- Van Rijn, a novel by Sarah Emily Miano, 2006

- I Am Rembrandt's Daughter, a novel by Lynn Cullen, 2007

- The Rembrandt Affair, a novel by Daniel Silva, 2011

- The Anatomy Lesson, a novel by Nina Siegal, 2014

- Rembrandt's Mirror, a novel by Kim Devereux, 2015

Music

[edit]- The Donna Summer song Dinner with Gershwin contain the lyrics "I want to watch Rembrandt sketch."

- The Scott Walker (singer) song Duchess features the lyrics "It's your Bicycle bells / and your Rembrandt swells"

Films

[edit]- The Stolen Rembrandt, a 1914 film directed by Leo D. Maloney and J. P. McGowan

- The Tragedy of a Great / Die Tragödie eines Großen, a 1920 film directed by Arthur Günsburg

- The Missing Rembrandt, a 1932 film directed by Leslie S. Hiscott

- Rembrandt, a 1936 film directed by Alexander Korda

- Rembrandt, a 1940 film

- Rembrandt in de schuilkelder / Rembrandt in the Bunker, a 1941 film directed by Gerard Rutten

- Rembrandt, a 1942 film directed by Hans Steinhoff

- Rembrandt: A Self-Portrait, a 1954 documentary film by Morrie Roizman

- Rembrandt, schilder van de mens / Rembrandt, Painter of Man, a 1957 film directed by Bert Haanstra

- Rembrandt fecit 1669, a 1977 film directed by Jos Stelling

- Rembrandt: The Public Eye and the Private Gaze, a 1992 documentary film by Simon Schama

- Rembrandt, a 1999 film directed by Charles Matton

- Rembrandt: Fathers & Sons, a 1999 film directed by David Devine

- Stealing Rembrandt, a 2003 film directed by Jannik Johansen and Anders Thomas Jensen

- Simon Schama's Power of Art: Rembrandt, a 2006 BBC documentary film series by Simon Schama

- Nightwatching, a 2007 film directed by Peter Greenaway

- Rembrandt's J'Accuse, a 2008 documentary film by Peter Greenaway

- Rembrandt en ik, a 2011 film directed by Marleen Gorris

- Schama on Rembrandt: Masterpieces of the Late Years, a 2014 documentary film by Simon Schama

Selected works

[edit]

- The Entombment of Christ (c. 1624) – Hunterian Museum and Art Gallery, Glasgow

- The Stoning of Saint Stephen (1625) – Musée des Beaux-Arts, Lyon

- Andromeda Chained to the Rocks (1630) – Mauritshuis, The Hague

- Old Man with a Gold Chain (c. 1631) – Art Institute of Chicago

- Jacob de Gheyn III (1632) – Dulwich Picture Gallery, London

- Philosopher in Meditation (1632) – The Louvre, Paris

- The Anatomy Lesson of Dr. Nicolaes Tulp (1632) – Mauritshuis, The Hague

- Judith at the Banquet of Holofernes (1634) – Museo del Prado, Madrid

- Descent from the Cross (1634) – Hermitage Museum, St. Petersburg. Looted from the Landgrave of Hesse-Kassel in 1806.[citation needed]

- Belshazzar's Feast (c. 1635-1638) – National Gallery, London

- The Prodigal Son in the Tavern (c. 1635) – Gemäldegalerie Alte Meister, Dresden

- Danaë (c. 1635, reworked before 1643) – Hermitage Museum, St. Petersburg

- The Scholar at the Lectern (1641) – Royal Castle, Warsaw

- The Girl in a Picture Frame (1641) – Royal Castle, Warsaw

- The Night Watch, formally The Militia Company of Captain Frans Banning Cocq (1642) – Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam

- Boaz and Ruth (1643) – Woburn Abbey, Bedfordshire & Gemaldegalerie, Berlin

- The Mill (1645/48) – National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.

- Susanna and the Elders (1647) – Gemäldegalerie, Berlin

- Christ Healing the Sick, also known as the Hundred Guilder Print (c. 1648) – Allen Memorial Art Museum, Oberlin, Ohio. Name derives from a print seller who claimed to have sold an impression of the print back to Rembrandt for 100 Guilders.

- Head of Christ (1648) – Gemäldegalerie, Berlin

- Aristotle Contemplating a Bust of Homer (1653) – Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

- The Three Crosses (1653) – Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

- Bathsheba at Her Bath (1654) – The Louvre, Paris

- Christ Presented to the People (c. 1655) – Various versions at different museums. One of the two largest prints made by Rembrandt.

- Pallas Athena (c. 1657) – Calouste Gulbenkian Museum, Lisbon

- Portrait of Dirck van Os (c. 1658) – Joslyn Art Museum, Omaha, Nebraska

- Self-Portrait with Beret and Turned-Up Collar (1659) – National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.

- Ahasuerus and Haman at the Feast of Esther (1660) – Pushkin Museum, Moscow

- The Conspiracy of Claudius Civilis (c. 1661-1662) – Nationalmuseum, Stockholm. The majority of the original painting is now lost as Rembrandt cut it up in order for it to be sold. It is also his last secular history painting.

- Syndics of the Drapers' Guild (1662) – Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam

- The Jewish Bride (c. 1665-1669) – Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam

- Haman before Esther (1665) – National Museum of Art of Romania, Bucharest[137]

- Self-Portrait at the Age of 63 (1669) – National Gallery, London. One of Rembrandt's last self-portraits.

- The Return of the Prodigal Son (1669) – Hermitage Museum, St. Petersburg. One of Rembrandt's last paintings.

Exhibitions

[edit]

- Sept–Oct 1898: Rembrandt Tentoonstelling (Rembrandt Exhibition), Stedelijk Museum, Amsterdam, the Netherlands.[138]

- Jan–Feb 1899: Rembrandt Tentoonstelling (Rembrandt Exhibition), Royal Academy, London.[138]

- 21 April 2011 – 18 July 2011: Rembrandt and the Face of Jesus, Musée du Louvre.[139]

- 16 September 2013 – 14 November 2013: Rembrandt: The Consummate Etcher, Syracuse University Art Galleries.[140]

- 19 May 2014 – 27 June 2014: From Rembrandt to Rosenquist: Works on Paper from the NAC's Permanent Collection, National Arts Club.[141]

- 19 October 2014 – 4 January 2015: Rembrandt, Rubens, Gainsborough and the Golden Age of Painting in Europe, Jule Collins Smith Museum of Art.[142]

- 15 October 2014 – 18 January 2015: Rembrandt: The Late Works, The National Gallery, London.[143]

- 12 February 2015 – 17 May 2015: Late Rembrandt, The Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam.[144]

- 16 September 2018 – 6 January 2019: Rembrandt – Painter as Printmaker, Denver Art Museum, Denver.[145]

- 24 August 2019 – 1 December 2019: Leiden circa 1630: Rembrandt Emerges, Agnes Etherington Art Centre, Kingston, Ontario.[146]

- 4 October 2019 – 2 February 2020: Rembrandt's Light, Dulwich Picture Gallery, London.[147]

- 18 February 2020 – 30 August 2020: Rembrandt and Amsterdam portraiture, 1590–1670 , Museo Nacional Thyssen-Bornemisza, Madrid.[148]

- 10 August 2020 – 1 November 2020: Young Rembrandt, Ashmolean Museum, Oxford.[149]

Paintings

[edit]Self-portraits

[edit]-

Self-portrait (1630) at Nationalmuseum in Stockholm

-

Self-Portrait with Velvet Beret and Furred Mantle (1634)

-

Self-Portrait at the Age of 34 (1640) at the National Gallery in London

-

Self-portrait (1655) an oil on walnut portrait cut down in size at. Kunsthistorisches Museum in Vienna

-

Self-Portrait (1660)

-

Self Portrait as Zeuxis (c. 1662), one of two self-portraits in which Rembrandt is turned to the left.[150] at Wallraf–Richartz Museum in Cologne

-

Self-portrait (1669)

-

Self-Portrait at the Age of 63 (1669, the year he died) at National Gallery in London

-

Rembrandt, Self-portrait, 1668–69, Galleria degli Uffizi, Florence

Other major paintings

[edit]-

The Stoning of Saint Stephen (1625), Rembrandt's first painting completed at the age of 19.[151] It is currently kept in the Musée des Beaux-Arts de Lyon.

-

Two old men disputing (1628) at the National Gallery of Victoria in Melbourne

-

Artist in His Studio (1628) at the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston

-

Bust of an old man with a fur hat (1630), a painting of Rembrandt's father

-

Andromeda (c. 1630)

-

The Philosopher in Meditation (c. 1632)

-

Anatomy Lesson of Dr. Nicolaes Tulp (c. 1632)

-

Portrait of Aeltje Uylenburgh (1632) at the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston

-

Portrait of a Young Woman (1632) at Allentown Art Museum in Allentown, Pennsylvania

-

Portrait of Saskia van Uylenburgh (c. 1633–34)

-

The Rape of Ganymede (1635) at Staatliche Kunstsammlungen in Dresden

-

The Blinding of Samson (1636), which Rembrandt gave to Huyghens

-

Susanna (1636)

-

Belshassar's Feast (c. 1636–38)

-

The Archangel Raphael Leaving Tobias' Family (1637) at the Louvre in Paris

-

Joseph's Dream (c. 1645)

-

Susanna and the Elders (1647)

-

The Mill (1648)

-

An Old Man in Red (c. 1652–54) at Hermitage Museum in Saint Petersburg, Russia

-

Aristotle with a Bust of Homer (1653) at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City

-

Portrait of Jan Six, a painting of a wealthy friend of Rembrandt (1654)

-

Bathsheba at Her Bath, modelled by Hendrickje (1654)

-

A Woman Bathing in a Stream, modelled by Hendrickje (1654)

-

Pallas Athene (c. 1655)

-

Woman in a Doorway (1657–58)

-

The Incredulity of St Thomas (1660) at the Pushkin Museum in Moscow, Russia

-

Saint Bartholomew (1661) at J. Paul Getty Museum in Los Angeles

-

The Syndics of the Drapers' Guild (1662)

-

The Conspiracy of Claudius Civilis (cut-down) (1661–62)

Drawings and etchings

[edit]-

Self-portrait, c. 1628–29, pen and brush and ink on paper

-

Self-portrait in a cap, with eyes wide open, 1630, etching and burin

-

Seated Old Man (c. 1630), red and black chalk on paper, Nationalmuseum, Stockholm

-

Suzannah and the Elders, 1634, drawing in Sanguine on paper, Kupferstichkabinett Berlin

-

Self-portrait with Saskia, 1636, etching, Rijksmuseum

-

An elephant, 1637, drawing in black chalk on paper, Albertina, Austria

-

Self-portrait leaning on a Sill, 1639, etching, National Gallery of Art

-

Christ and the woman taken in adultery, c. 1639–41, drawing in ink, Louvre

-

Beggars I., c. 1640–42, ink on paper, Warsaw University Library

-

The Windmill, 1641, etching

-

The Diemerdijk at Houtewael (near Amsterdam), 1648–49, pen and brown ink, brown wash, Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen

-

Virgin and Child with a Cat, 1654, original copper etching plate above (the original copper plate), in Victoria and Albert Museum, example of the print below

-

Christ presented to the People, drypoint etching, 1655, state I of VIII, Rijksmuseum

-

Two Old Men in Conversation /Two Jews in Discussion, Walking, year unknown, black chalk and brown ink on paper, Teylers Museum

-

A child being taught to walk (c. 1635)

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ This version of his first name, "Rembrandt" with a "d," first appeared in his signatures in 1633. Until then, he had signed with a combination of initials or monograms. In late 1632, he began signing solely with his first name, "Rembrant". He added the "d" in the following year and stuck to this spelling for the rest of his life. Although scholars can only speculate, this change must have had a meaning for Rembrandt, which is generally interpreted as his wanting to be known by his first name like the great figures of the Italian Renaissance: Leonardo, Raphael etc., who did not sign with their last names, if at all.[7]

- ^ Rembrandt promised the owner—a woman with mental problems—to pay a quarter of the purchase price within a year;[20] the rest within five to six years. For some reason the purchase was not registered at the town hall and had to be renewed in 1653.[21]

- ^ Their son Rombartus died two months after his birth and their daughter Cornelia died at just three weeks of age. A second daughter, also named Cornelia, died after living barely over a month.

- ^ His children were christened in Dutch Reformed churches in Amsterdam: four in the Old Church and Titus, in the Southern Church.[25]

- ^ Five years later he didn't support her release without the presence of her brother, a sailor. In August 1656 Geertghe Dircx was listed as one of Rembrandt's seven major creditors.

- ^ Quite a few people were in debt after the First Anglo-Dutch War.[35] The Dutch were driven from Brazil too; the 'Brazilian Adventure' cost the Dutch merchant community dearly.[36]

- ^ Jan van de Capelle bought 500 of the drawings/prints by Lucas van Leyden, Hercules Seghers and Goltzius among others.

- ^ Useful totals of the figures from various different oeuvre catalogues, often divided into classes along the lines of: "very likely authentic", "possibly authentic" and "unlikely to be authentic" are given at the Online Rembrandt catalogue[69]

- ^ Two hundred years ago Bartsch listed 375. More recent catalogues have added three (two in unique impressions) and excluded enough to reach totals as follows: Schwartz, pp. 6, 289; Münz 1952, 279; Boon 1963, 287 Print Council of America – but Schwartz's total quoted does not tally with the book.

- ^ It is not possible to give a total, as a new wave of scholarship on Rembrandt drawings is still in progress – analysis of the Berlin collection for an exhibition in 2006/7 has produced a probable drop from 130 sheets there to about 60. Codart.nl[70] The British Museum is due to publish a new catalogue after a similar exercise.

- ^ While the popular interpretation is that these paintings represent a personal and introspective journey, it is possible that they were painted to satisfy a market for self-portraits by prominent artists. Van de Wetering, p. 290.

- ^ Such as Otto Benesch,[99][100][101] David Hockney,[102] Nigel Konstam, Jakob Rosenberg, Gary Schwartz, and Seymour Slive.[103][104]

- ^ The Rijksmuseum has a smaller copy of what is thought to be the full original composition.

References

[edit]- ^ a b c Or possibly 1607 as on 10 June 1634 he himself claimed to be 26 years old. See Is the Rembrandt Year being celebrated one year too soon? One year too late? Archived 21 November 2010 at the Wayback Machine and (in Dutch) J. de Jong, Rembrandts geboortejaar een jaar te vroeg gevierd Archived 18 July 2010 at the Wayback Machine for sources concerning Rembrandt's birth year, especially supporting 1607. However, most sources continue to use 1606.

- ^ "Rembrandt" Archived 4 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine. Random House Webster's Unabridged Dictionary.

- ^ a b Gombrich, p. 420.

- ^ Gombrich, p. 427.

- ^ Clark 1969, p. 203

- ^ W. Liedtke (2007) Dutch painting in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, p. 687

- ^ "Rembrandt Signature Files". www.rembrandt-signature-file.com. Archived from the original on 9 April 2016.

- ^ Bull, et al., p. 28.

- ^ a b (in Dutch) Rembrandt biography in De groote schouburgh der Nederlantsche konstschilders en schilderessen (1718) by Arnold Houbraken, courtesy of the Digital library for Dutch literature

- ^ Joris van Schooten as teacher of Rembrandt and LievensArchived 26 December 2016 at the Wayback Machine in Simon van Leeuwen's Korte besgryving van het Lugdunum Batavorum nu Leyden, Leiden, 1672

- ^ Slive has a comprehensive biography, pp. 55ff.

- ^ Schwarz, G. (1987) Rembrandt, p. 134.

- ^ Slive, pp. 60, 65

- ^ Slive, pp. 60–61

- ^ "Netherlands, Noord-Holland Province, Church Records, 1553–1909 Image Netherlands, Noord-Holland Province, Church Records, 1553–1909; pal:/MM9.3.1/TH-1971-31164-16374-68". Familysearch.org. Archived from the original on 5 June 2016. Retrieved 7 April 2014.

- ^ Registration of the banns of Rembrandt and Saskia, kept at the Amsterdam City Archives

- ^ a b c Bull, et al., p. 28

- ^ a b "Rijksmuseum". Rijksmuseum.

- ^ "RemDoc".

- ^ Anrooij, Wim van; Hoftijzer, Paul (28 June 2017). Vijftien strekkende meter: Nieuwe onderzoeksmogelijkheden in het archief van de Bibliotheca Thysiana. Uitgeverij Verloren. ISBN 9789087046842 – via Google Books.

- ^ a b c "Rembrandt's boedelafstand door jhr. mr. J.F. Backer., Elseviers Geïllustreerd Maandschrift. Jaargang 29". DBNL.

- ^ Adams, p. 660

- ^ "Pieter C. Vis: Andries de Graeff (1611–1678) 't Gezagh is heerelyk: doch vol bekommeringen" (PDF).

- ^ "Portrait of Andries de Graeff (1611–1678), Burgomaster of Amsterdam". The Leiden Collection.

- ^ "Doopregisters, Zoek" (in Dutch). Amsterdam City Archive. Retrieved 7 March 2023.

- ^ a b Slive, p. 71

- ^ "Indexen". archief.amsterdam.

- ^ Crenshaw, Paul (2006). Rembrandt's bankruptcy: the artist, his patrons, and the art market in seventeenth-century Nederlands. Cambridge: University Press. ISBN 978-0521858250. OCLC 902528433.

- ^ "Dircks, Geertje (ca. 1610-1656?)". Resources Huygens ING.

- ^ C. Driessen, pp. 151–157

- ^ Gary Schwartz (1987) Rembrandt. Zijn leven, zijn schilderijen, p. 248.

- ^ G. Schwartz, pp. 292–293

- ^ Slive, p. 82

- ^ "Rembrandt". Voetnoot.org.

- ^ Dehing, P. (2012). Geld in Amsterdam. Wisselbank en wisselkoersen, 1650–1725. [Universiteit van Amsterdam], p. 142

- ^ Professor P. C. Emmer, review of The Rise of Commercial Empires England and the Netherlands in the Age of Mercantilism, 1650–1770, (review no. 345) https://reviews.history.ac.uk/review/345 Date accessed: 26 March 2023

- ^ Wexuan, Li. "Review of: 'Rembrandts plan: De ware geschiedenis van zijn faillissement", Oud Holland Reviews, April 2020.

- ^ Broos, B. (1999) Das Leben Rembrandts van Rijn (1606–1669). In: Rembrandt Selbstbildnisse, p. 79.

- ^ a b "Drie vragen aan Machiel Bosman | Rembrandts plan | Faillissement Rembrandt van Rijn".

- ^ C.M. in ’t Veld (2019) Rembrandts boedelafstand: een institutionele en politieke benadering

- ^ Wexuan, Li. "Review of: 'Rembrandts plan: De ware geschiedenis van zijn faillissement", Oud Holland Reviews, April 2020.

- ^ a b M. Bosman (2019) Rembrandts plan. De ware geschiedenis van zijn faillissement

- ^ Crenshaw, P. (2006) Rembrandt's Bankruptcy. The artist, his patrons and the art market in seventeenth-century Netherlands, pp. 61, 76.

- ^ Ruysscher, Dave De; Veld, Cornelis In ’T (26 April 2021). "Rembrandt's insolvency: The artist as legal actor" (PDF). Oud Holland – Journal for Art of the Low Countries. 134 (1): 9–24. doi:10.1163/18750176-13401002. S2CID 236619973 – via brill.com.

- ^ Schwartz (1984), pp. 288–291

- ^ Slive, p. 84

- ^ "Inventarissen". archief.amsterdam.

- ^ Dudok van Heel, S.A.C. (1969) De Rembrandt's in de verzamelingen Hinlopen. In: Maandblad Amstelodamum, pp. 233-237. (In Dutch.)

- ^ "Inventarissen". archief.amsterdam.

- ^ Wexuan, Li. "Review of: 'Rembrandts plan: De ware geschiedenis van zijn faillissement", Oud Holland Reviews, April 2020.

- ^ Clark, 1974 p. 105

- ^ "De geldzaken van Rembrandt - Stadsarchief Amsterdam".

- ^ Clark 1974, pp. 60–61

- ^ Bull, et al., p. 29.

- ^ Jan Veth (1906) Rembrandt's verwarde zaken DBNL

- ^ Ruysscher, Dave De; Veld, Cornelis In ’T (26 April 2021). "Rembrandt's insolvency: The artist as legal actor" (PDF). Oud Holland – Journal for Art of the Low Countries. 134 (1): 9–24. doi:10.1163/18750176-13401002. S2CID 236619973 – via brill.com.

- ^ Bailly, M.-Ch le; Bailly, Maria Charlotte Le (28 June 2008). Hof van Holland, Zeeland en West-Friesland: de hoofdlijnen van het procederen in civiele zaken voor het Hof van Holland, Zeeland en West-Friesland zowel in eerste instantie als in hoger beroep. Uitgeverij Verloren. ISBN 978-9087040567 – via Google Books.

- ^ Wexuan, Li. "Review of: 'Rembrandts plan: De ware geschiedenis van zijn faillissement", Oud Holland Reviews, April 2020.

- ^ "380 Whitewashing Rembrandt, part 2 – Gary Schwartz Art Historian". 1 March 2020.

- ^ Clark 1978, p. 34

- ^ Burial register of the Westerkerk with record of Rembrandt's burial, kept at the Amsterdam City Archives

- ^ "Cornelia van Rijn".

- ^ Dudok van Heel, S.A.C. (1987) Dossier Rembrandt, pp. 86–88

- ^ "Rembrandt made a mess of his legal and financial life". Leiden University. 16 November 2021.

- ^ Rembrandt’s insolvency: No preconceived plan, but smart entrepreneurship. VUB, 2021

- ^ Hughes, p. 6

- ^ "A Web Catalogue of Rembrandt Paintings". 28 July 2012. Archived from the original on 28 July 2012.

- ^ "Institute Member Login – Institute for the Study of Western Civilization". Archived from the original on 29 September 2007.

- ^ "A Web Catalogue of Rembrandt Paintings". Archived from the original on 13 May 2012. Retrieved 10 July 2007.

- ^ "Rembrandt, der Zeichner". Archived from the original on 27 May 2016. Retrieved 3 October 2007.

- ^ "Schwartzlist 301 – Blog entry by the Rembrandt scholar Gary Schwartz". Garyschwartzarthistorian.nl. 3 January 2010. Archived from the original on 22 February 2012. Retrieved 17 February 2012.

- ^ White and Buvelot 1999, p. 10.

- ^ Taylor, Michael (2007).Rembrandt's Nose: Of Flesh & Spirit in the Master's Portraits Archived 5 May 2016 at the Wayback Machine p. 21, D.A.P./Distributed Art Publishers, Inc., New York ISBN 978-1933045443'

- ^ Durham, p. 60.

- ^ Bull, et al., pp. 11–13.

- ^ Clough, p. 23

- ^ Clark 1978, p. 28

- ^ van der Wetering, p. 268.

- ^ van de Wetering, pp. 160, 190.

- ^ Ackley, p. 14.

- ^ a b c van de Wetering, p. 284.

- ^ van de Wetering, p. 285.

- ^ van de Wetering, p. 287.

- ^ van de Wetering, p. 286.

- ^ van de Wetering, p. 288.

- ^ van de Wetering, pp. 163–165.

- ^ van de Wetering, p. 289.

- ^ van de Wetering, pp. 155–165.

- ^ van de Wetering, pp. 157–158, 190.

- ^ "In Rembrandt's (late) great portraits we feel face to face with real people, we sense their warmth, their need for sympathy and also their loneliness and suffering. Those keen and steady eyes that we know so well from Rembrandt's self-portraits must have been able to look straight into the human heart." Gombrich, p. 423.

- ^ "It (The Jewish Bride) is a picture of grown-up love, a marvelous amalgam of richness, tenderness, and trust... the heads which, in their truth, have a spiritual glow that painters influenced by the classical tradition could never achieve." Clark, p. 206.

- ^ Schwartz, 1994, pp. 8–12

- ^ White 1969, pp. 5–6

- ^ White 1969, p. 6

- ^ White 1969, pp. 6, 9–10

- ^ White, 1969 pp. 6–7

- ^ Christiaan Vogelaar & Gregor J.M. Weber (2006) Rembrandts Landschappen

- ^ See Schwartz, 1994, where the works are divided by subject, following Bartsch.

- ^ Benesch, Otto: The Drawings of Rembrandt: First Complete Edition in Six Volumes. (London: Phaidon, 1954–57)

- ^ Benesch, Otto: Rembrandt as a Draughtsman: An Essay with 115 Illustrations. (London: Phaidon Press, 1960)

- ^ Benesch, Otto: The Drawings of Rembrandt. A Critical and Chronological Catalogue [2nd ed., 6 vols.]. (London: Phaidon, 1973)

- ^ Lewis, Tim (16 November 2014). "David Hockney: 'When I'm working, I feel like Picasso, I feel I'm 30'". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 16 May 2020. Retrieved 16 June 2020.

- ^ Slive, Seymour: The Drawings of Rembrandt: A New Study. (London: Thames & Hudson, 2009)

- ^ Silve, Seymour: The Drawings of Rembrandt. (London: Thames & Hudson, 2019)

- ^ a b Mendelowitz, Daniel Marcus: Drawing. (New York: Holt, Rinehart & Winston, Inc., 1967), p. 305.

- ^ a b Sullivan, Michael: The Meeting of Eastern and Western Art. (Berkeley/Los Angeles: University of California Press, 1989), p. 91

- ^ Schrader, Stephanie; et al. (eds.): Rembrandt and the Inspiration of India Archived 1 August 2020 at the Wayback Machine. (Los Angeles, CA: J. Paul Getty Museum, 2018) ISBN 978-1606065525

- ^ "Rembrandt and the Inspiration of India (catalogue)" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 18 October 2019. Retrieved 18 October 2019.

- ^ "In Paintings: Rembrandt & his Mughal India Inspiration". 3 September 2017. Archived from the original on 23 May 2018. Retrieved 12 May 2018.

- ^ Ganz, James (2013). Rembrandt's Century. San Francisco, CA: Fine Arts Museum of San Francisco. p. 45. ISBN 978-3791352244.

- ^ Beliën, H & P. Knevel (2006) Langs Rembrandts roem, pp. 92–121

- ^ John Russell (1 December 1985). "Art View; In Search of the Real Thing". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 1 July 2017. Retrieved 12 February 2017.

- ^ "The Rembrandt Research Project: Past, Present, Future" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 22 August 2014. Retrieved 11 August 2014.

- ^ See "Further Battles for the 'Lisowczyk' (Polish Rider) by Rembrandt" Zdzislaw Zygulski, Jr., Artibus et Historiae, Vol. 21, No. 41 (2000), pp. 197–205. Also New York Times story Archived 8 January 2008 at the Wayback Machine. There is a book on the subject:Responses to Rembrandt; Who painted the Polish Rider? by Anthony Bailey (New York, 1993)

- ^ Schama, Simon (1999). Rembrandt's Eyes. Knopf, p. 720.

- ^ Schama, pp. 582–591.

- ^ "Rembrandt Pilate Washing His Hands Oil Painting Reproduction". Outpost Art. Archived from the original on 12 January 2015. Retrieved 1 January 2015.

- ^ "Entertainment | Lost Rembrandt works discovered". BBC News. 23 September 2005. Archived from the original on 22 December 2006. Retrieved 7 October 2009.

- ^ Brown, Mark (23 May 2014), "Rembrandt expert urges National Gallery to rethink demoted painting", The Guardian, archived from the original on 21 September 2016, retrieved 21 December 2015

- ^ "...Rembrandt was not always the perfectly consistent, logical Dutchman he was originally anticipated to be." Ackley, p. 13.

- ^ van de Wetering, p. x.

- ^ Kühn, Hermann. 'Untersuchungen zu den Pigmenten und Malgründen Rembrandts, durchgeführt an den Gemälden der Staatlichen Kunstsammlungen Dresden'(Examination of pigments and grounds used by Rembrandt, analysis carried out on paintings in the Staatlichen Kunstsammlungen Dresden), Maltechnik/Restauro, issue 4 (1977): 223–233

- ^ Kühn, Hermann. 'Untersuchungen zu den Pigmenten und Malgründen Rembrandts, durchgeführt an den Gemälden der Staatlichen Kunstsammlungen Kassel' (Examination of pigments and grounds used by Rembrandt, analysis carried out on paintings in the Staatlichen Kunstsammlungen Kassel), Maltechnik/Restauro, volume 82 (1976): 25–33

- ^ Van Loon, A., Noble, P., Krekeler, A., van der Snickt, G., Janssens, K., Abe, Y., Nakai, I., & Dik, J. 2017. "Artificial orpiment, a new pigment in Rembrandt's palette". Heritage Science, 5 (26)

- ^ Rembrandt, Saskia as Flora Archived 15 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine, ColourLex

- ^ a b Bomford, D. et al., Art in the making: Rembrandt, New edition, Yale University Press, 2006

- ^ Rembrandt, Belshazzar's Feast, Pigment analysis Archived 7 April 2016 at the Wayback Machine at ColourLex

- ^ "Resources Rembrandt". ColourLex. Archived from the original on 24 February 2021. Retrieved 23 February 2021.

- ^ "The Rembrandt Database". Archived from the original on 23 August 2015. Retrieved 6 July 2015.

- ^ Roberts, Russell. Rembrandt. Mitchell Lane Publishers, 2009. ISBN 978-1612287607. p. 13.

- ^ Chronology of his signatures (pdf) Archived 3 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine with examples. Source: www.rembrandt-signature-file.com

- ^ Slive, p. 60

- ^ Rembrandt pupils (under Leraar van) in the RKD

- ^ Clark 1974, pp. 147–150. See the catalogue in Further reading for the location of all accepted Rembrandts

- ^ G. Schwartz (1987) Rembrandt, zijn leven, zijn schilderen.

- ^ "The Lanckoroński Collection – Rembrandt's Paintings". zamek-krolewski.pl. Archived from the original on 20 May 2014. Retrieved 20 May 2014.

The works of art which Karolina Lanckorońska gave to the Royal Castle in 1994 was one of the most invaluable gift's made in the museum's history.

- ^ "The National Museum of Art of Romania – Rembrandt – Haman before Esther". www.mnar.arts.ro. Archived from the original on 7 November 2021. Retrieved 15 July 2020.

- ^ a b "Rembrandt tentoonstilling". www.nga.gov. Archived from the original on 14 August 2019. Retrieved 14 August 2019.

- ^ "Rembrandt and the Face of Jesus". Archived from the original on 31 January 2015. Retrieved 13 January 2015.

- ^ "Rembrandt: The Consummate Etcher". Archived from the original on 13 January 2015. Retrieved 13 January 2015.

- ^ "From Rembrandt to Rosenquist: Works on Paper from the NAC's Permanent Collection". Archived from the original on 31 January 2015. Retrieved 11 January 2015. Retrieved 11 January 2015. "MutualArt.com". Archived from the original on 10 January 2015. Retrieved 11 January 2015.

- ^ "Rembrandt, Rubens, Gainsborough and the Golden Age of Painting in Europe". Archived from the original on 31 January 2015. Retrieved 11 January 2015. Retrieved 11 January 2015. "MutualArt.com". Archived from the original on 10 January 2015. Retrieved 11 January 2015.

- ^ "Rembrandt: The Late Works". Archived from the original on 31 January 2015. Retrieved 11 January 2015. "MutualArt.com". Archived from the original on 10 January 2015. Retrieved 11 January 2015. Promoted in Rembrandt: From the National Gallery, London and Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam 2014 at IMDb

- ^ "MutualArt – Auctions, Exhibitions and Analysis for over 400,000 artists". www.mutualart.com. Archived from the original on 10 October 2018. Retrieved 10 October 2018.

- ^ "MutualArt.com – The Web's Largest Art Information Service". www.mutualart.com. Archived from the original on 10 October 2018. Retrieved 10 October 2018.

- ^ "Leiden circa 1630: Rembrandt Emerges | Agnes Etherington Art Centre". agnes.queensu.ca. Archived from the original on 15 January 2019. Retrieved 15 January 2019.

- ^ "Rembrandt's Light | Dulwich Picture Gallery". www.dulwichpicturegallery.org.uk. Archived from the original on 6 August 2020. Retrieved 12 February 2020.

- ^ "Exhibitions Rembrandt and Amsterdam portraiture, 1590–1670". Madrid: Museo Nacional Thyssen Bornemisza. 2020. Archived from the original on 9 October 2020. Retrieved 19 September 2020.

- ^ "Welcome | Ashmolean Museum". Archived from the original on 24 September 2020. Retrieved 23 September 2020.

- ^ White, 200

- ^ Starcky, Emmanuel (1990). Rembrandt. Hazan. p. 45. ISBN 978-2850252129.

Works cited

[edit]- Ackley, Clifford, et al., Rembrandt's Journey, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, 2004. ISBN 0-87846-677-0

- Adams, Laurie Schneider (1999). Art Across Time. Volume II. New York: McGraw-Hill College.

- Bomford, D. et al., Art in the making: Rembrandt, New edition, Yale University Press, 2006

- Bull, Duncan, et al., Rembrandt-Caravaggio, Rijksmuseum, 2006.

- Buvelot, Quentin, White, Christopher (eds), Rembrandt by himself, 1999, National Gallery

- Clark, Kenneth (1969). Civilisation: a personal view. New York: Harper & Row. ISBN 978-0-06-010801-4.

- Clark, Kenneth, An Introduction to Rembrandt, 1978, London, John Murray/Readers Union, 1978

- Clough, Shepard B. (1975). European History in a World Perspective. D.C. Heath and Company, Los Lexington, MA. ISBN 978-0-669-85555-5.

- Driessen, Christoph, Rembrandts vrouwen, Bert Bakker, Amsterdam, 2012. ISBN 978-90-351-3690-8

- Durham, John I. (2004). Biblical Rembrandt: Human Painter in a Landscape of Faith. Mercer University Press. ISBN 978-0-86554-886-2.

- Gombrich, E.H., The Story of Art, Phaidon, 1995. ISBN 0-7148-3355-X

- Hughes, Robert (2006), "The God of Realism", The New York Review of Books, vol. 53, no. 6

- The Complete Etchings of Rembrandt Reproduced in Original Size, Gary Schwartz (editor). New York: Dover, 1988. ISBN 0-486-28181-7

- Slive, Seymour, Dutch Painting, 1600–1800, Yale UP, 1995, ISBN 0-300-07451-4

- van de Wetering, Ernst in Rembrandt by himself, 1999 National Gallery, London/Mauritshuis, The Hague, ISBN 1-85709-270-8

- van de Wetering, Ernst, Rembrandt: The Painter at Work, Amsterdam University Press, 2000. ISBN 0-520-22668-2

- White, Christopher, The Late Etchings of Rembrandt, 1999, British Museum/Lund Humphries, London ISBN 978-90-400-9315-9

Further reading

[edit]- Catalogue raisonné: Stichting Foundation Rembrandt Research Project:

- A Corpus of Rembrandt Paintings – Volume I, which deals with works from Rembrandt's early years in Leiden (1629–1631), 1982

- A Corpus of Rembrandt Paintings – Volume II: 1631–1634. Bruyn, J., Haak, B. (et al.), Band 2, 1986, ISBN 978-90-247-3339-2

- A Corpus of Rembrandt Paintings – Volume III, 1635–1642. Bruyn, J., Haak, B., Levie, S.H., van Thiel, P.J.J., van de Wetering, E. (Ed. Hrsg.), Band 3, 1990, ISBN 978-90-247-3781-9

- A Corpus of Rembrandt Paintings – Volume IV. Ernst van de Wetering, Karin Groen et al. Springer, Dordrecht, the Netherlands. ISBN 1-4020-3280-3. p. 692. (Self-Portraits)

- Rembrandt. Images and metaphors, Christian and Astrid Tümpel (editors), Haus Books London 2006 ISBN 978-1-904950-92-9

- Anthony M. Amore; Tom Mashberg (2012). Stealing Rembrandts: The Untold Stories of Notorious Art Heists. St. Martin's Publishing. ISBN 978-0-230-33990-3.

External links

[edit]- A biography of the artist Rembrandt Harmensz. van Rijn from the National Gallery, London

- Works and literature on Rembrandt from Pubhist.com

- The Drawings of Rembrandt: a revision of Otto Benesch's catalogue raisonné by Martin Royalton-Kisch (in progress)

- Rembrandt's house in Amsterdam Site of the Rembrandt House Museum in Amsterdam, with images of many of his etchings

- 114 artworks by or after Rembrandt at the Art UK site

- Works by or about Rembrandt at the Internet Archive

- Rembrandt van Rijn, General Resources

- The transparent connoisseur 3: the 30 million pound question by Gary Schwartz

- Rembrandt

- The Rembrandt Database research data on the paintings, including the full contents of the first volumes of A Corpus of Rembrandt Paintings by the Rembrandt Research Project

- Die Urkunden über Rembrandt by C. Hofstede de Groot (1906).

- Rembrandt

- 1606 births

- 1669 deaths

- Art collectors from Amsterdam

- Artists from Leiden

- Dutch art dealers

- Dutch Christians

- Dutch draughtsmen

- Dutch etchers

- Dutch Golden Age painters

- Dutch Golden Age printmakers

- Dutch male painters

- Dutch portrait painters

- Dutch printmakers

- Engravers from Amsterdam

- Leiden University alumni

- Painters from Amsterdam

- People celebrated in the Lutheran liturgical calendar

- 17th-century Dutch painters

![Self Portrait as Zeuxis (c. 1662), one of two self-portraits in which Rembrandt is turned to the left.[150] at Wallraf–Richartz Museum in Cologne](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/5/58/Rembrandt_Harmensz._van_Rijn_142.jpg/118px-Rembrandt_Harmensz._van_Rijn_142.jpg)

![The Stoning of Saint Stephen (1625), Rembrandt's first painting completed at the age of 19.[151] It is currently kept in the Musée des Beaux-Arts de Lyon.](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/7/75/Rembrandt-Lapidation-Saint-%C3%89tienne-MBA-Lyon.jpg/170px-Rembrandt-Lapidation-Saint-%C3%89tienne-MBA-Lyon.jpg)

![A young woman sleeping (c. 1654). Shows Rembrandt's calligraphic-style draughtsmanship.[105][106]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/1/14/Amsterdam_-_Late_Rembrandt_Exposition_2015_-_Young_Woman_Sleeping_1654_B_%28cropped%29.jpg/98px-Amsterdam_-_Late_Rembrandt_Exposition_2015_-_Young_Woman_Sleeping_1654_B_%28cropped%29.jpg)