Turpan

Turpan

Turfan | |

|---|---|

Jiaohe Ruins | |

Turpan (red) in Xinjiang (orange) | |

| Coordinates (Turpan municipal government): 42°57′04″N 89°11′22″E / 42.9512°N 89.1895°E | |

| Country | People's Republic of China |

| Region | Xinjiang |

| County-level divisions | 3 |

| Prefecture seat | Gaochang District |

| Area | |

| • Prefecture-level city | 69,759 km2 (26,934 sq mi) |

| • Urban | 13,650 km2 (5,270 sq mi) |

| Lowest elevation | −154 m (−505 ft) |

| Population (2020) | |

| • Prefecture-level city | 693,988 |

| • Density | 9.9/km2 (26/sq mi) |

| • Urban | 317,443 |

| • Urban density | 23/km2 (60/sq mi) |

| Demographics | |

| • Major ethnic groups |

|

| GDP[1] | |

| • Prefecture-level city | CN¥ 31.0 billion US$ 4.7 billion |

| • Per capita | CN¥ 49,279 US$ 7,180 |

| Time zone | UTC+8 (China Standard) |

| ISO 3166 code | CN-XJ-04 |

| Climate | BWk |

| Website | Turpan Prefecture-level city Government |

| Turpan | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chinese name | |||||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 吐鲁番 | ||||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 吐魯番 | ||||||||||

| |||||||||||

| Uyghur name | |||||||||||

| Uyghur | تورپان | ||||||||||

| |||||||||||

Turpan (Uyghur: تۇرپان), generally known in English as Turfan (Chinese: 吐鲁番), is a prefecture-level city located in the east of the autonomous region of Xinjiang, China. It has an area of 69,759 km2 (26,934 sq mi) and a population of 693,988 (2020). The historical center of the prefectural area has shifted a number of times, from Yar-Khoto (Jiaohe, 10 km or 6.2 mi to the west of modern Turpan) to Qocho (Gaochang, 30 km or 19 mi to the southeast of Turpan) and to Turpan itself.[2]

Names

[edit]Historically, many settlements in the Tarim Basin, being situated between Chinese, Turkic, Mongolian, and Persian language users, have a number of cognate names. Turpan or Turfan/Tulufan is one such example. The original name of the city is unknown. The form Turfan, while older than Turpan, was not used until the middle of the 2nd millennium CE and its use became widespread only in the post-Mongol period.[3]

History

[edit]Turpan has long been the centre of a fertile oasis (with water provided by the karez canal system) and an important trade centre. It was historically located along the Silk Road. At that time, other kingdoms of the region included Korla and Yanqi.

Along with city-states such as Krorän (Loulan) and Kucha, Turfan appears to have been inhabited by people speaking the Indo-European Tocharian languages in prehistory.[4]

The Jushi Kingdom ruled the area in the 1st millennium BC, until it was conquered by the Chinese Han dynasty in 107 BC.[5][6] It was subdivided into two kingdoms in 60 BC, between the Han and its enemy the Xiongnu Empire. The city changed hands several times between the Xiongnu and the Han, interspersed with short periods of independence.[7] Nearer Jushi has been linked to the Turpan Oasis,[8] while Further Jushi to the north of the mountains near modern Jimsar.

After the fall of the Han dynasty in 220, the region was virtually independent but tributary to various dynasties. Until the 5th century AD, the capital of this kingdom was Jiaohe (modern Yarghul 16 kilometres (9.9 mi) west of Turpan).[9]

Many Han Chinese along with Sogdians settled in Turfan during the post Han dynasty era. The Chinese character dominated Turfan in the eyes of the Sogdians. Kuchean speakers made up the original inhabitants before the Chinese and Sogdian influx. The oldest evidence of the use of Chinese characters was found in Turfan in a document dated to 273 AD.[10]

In 327, the Gaochang Commandery (jùn) was created in the Turfan area by the Former Liang under Zhang Jun. The Chinese set up a military colony/garrison and organized the land into multiple divisions. Han Chinese colonists from the Hexi region and the central plains also settled in the region.[11] Gaochang was successively ruled by the Former Liang, Former Qin and Northern Liang.[12]

In 439, remnants of the Northern Liang,[13] led by Juqu Wuhui and Juqu Anzhou, fled to Gaochang where they would hold onto power until 460 when they were conquered by the Rouran Khaganate.

Gaochang Kingdom

[edit]

At the time of its conquest by the Rouran Khaganate, there were more than ten thousand Han Chinese households in Gaochang.[14] The Rouran Khaganate, which was based in Mongolia, appointed a Han Chinese named Kan Bozhou to rule as King of Gaochang in 460, and it became a separate vassal kingdom of the Khaganate.[15] Kan was dependent on Rouran backing.[16] Yicheng and Shougui were the last two kings of the Chinese Kan family to rule Gaochang.

At this time the Gaoche was rising to challenge power of the Rouran in the Tarim Basin. The Gaoche king Afuzhiluo killed King Kan Shougui, who was the nephew of Kan Bozhou.[17][18] and appointed a Han from Dunhuang, named Zhang Mengming (張孟明), as his own vassal King of Gaochang.[19][20] Gaochang thus passed under Gaoche rule.

Later, Zhang Mengming was killed in an uprising by the people of Gaochang and replaced by Ma Ru (馬儒). In 501, Ma Ru himself was overthrown and killed, and the people of Gaochang appointed Qu Jia (麴嘉) from Jincheng Commandery as their king.[18] Qu Jia at first pledged allegiance to the Rouran, but the Rouran khaghan was soon killed by the Gaoche and he had to submit to Gaoche overlordship. Later, when the Göktürks emerged as the supreme power in the region, the Qu dynasty of Gaochang became vassals of the Göktürks.[21]

While the material civilization of Kucha to its west in this period remained chiefly Indo-Iranian in character, in Gaochang it gradually merged into the Tang aesthetics.[22] Qu Wentai, King of Gaochang, was a main patron of the Tang pilgrim and traveller Xuanzang.[22]

Tang conquest

[edit]

The Tang dynasty had reconquered the Tarim Basin by the 7th century AD and for the next three centuries the Tibetan Empire, the Tang dynasty, and the Turks fought over dominion of the Tarim Basin. Sogdians and Chinese engaged in extensive commercial activities with each other under Tang rule. The Sogdians were mostly Mazdaist at this time. The Turpan region was renamed Xi Prefecture (西州) when the Tang conquered it in 640 AD,[23] had a history of commerce and trade along the Silk Road already centuries old; it had many inns catering to merchants and other travelers, while numerous brothels are recorded in Kucha and Khotan.[24] According to Valerie Hansen, even before the Tang conquest, Han ethnic presence was already so extensive that the cultural alignment of the city led to Turpan's name in the Sogdian language becoming known as "Chinatown" or "Town of the Chinese". As late as the tenth century, the Persian source Hudud Al-Alam continued to refer to the town as Chīnanjkanth (Chinese town).[23][25]

In Astana Cemetery, a contract written in Sogdian detailing the sale of a Sogdian girl to a Chinese man was discovered dated to 639 AD. Individual slaves were common among silk route houses; early documents recorded an increase in the selling of slaves in Turpan.[26] Twenty-one 7th-century marriage contracts were found that showed, where one Sogdian spouse was present, for 18 of them their partner was a Sogdian. The only Sogdian men who married Chinese women were highly eminent officials.[27] Several commercial interactions were recorded, for example a camel was sold priced at 14 silk bolts in 673,[28][29] and a Chang'an native bought a girl age 11 for 40 silk bolts in 731 from a Sogdian merchant.[30] Five men swore that the girl was never free before enslavement, since the Tang Code forbade commoners to be sold as slaves.[23]

The Tang dynasty became weakened considerably due to the An Lushan Rebellion, and the Tibetans took the opportunity to expand into Gansu and the Western Regions. The Tibetans took control of Turfan in 792.

Clothing for corpses was made out of discarded, used paper in Turfan which is why the Astana graveyard is a source of a plethora of texts.[31]

Seventh or 8th century dumplings and wontons were found in Turfan.[32]

Uyghur rule

[edit]In 803, the Uyghurs of the Uyghur Khaganate seized Turfan from the Tibetans. The Uyghur Khaganate however was destroyed by the Kirghiz and its capital Ordu-Baliq in Mongolia sacked in 840. The defeat resulted in the mass movement of the Uyghurs out of Mongolia and their dispersal into Gansu and Central Asia, and many joined other Uyghurs already present in Turfan. In the early twentieth century, a collection of some 900 Christian manuscripts dating to the ninth to the twelfth centuries was found by the German Turfan expeditions at a monastery site at Turfan.[33]

Idikut kingdom

[edit]

The Uyghurs established a Kingdom in the Turpan region with its capital in Gaochang or Kara-Khoja. The kingdom was known as the Uyghuria Idikut state or Kara-Khoja Kingdom that lasted from 856 to 1389 AD. The Uyghurs were Manichaean but later converted to Buddhism and funded the construction of cave temples in the Bezeklik Caves. The Uyghurs formed an alliance with the rulers of Dunhuang. The Uyghur state later became a vassal state of the Kara-Khitans and then as a vassal of the Mongol Empire. This Kingdom was led by the Idikuts or Saint Spiritual Rulers. The last Idikut left Turpan area in 1284 for Kumul and then Gansu to seek protection of the Yuan dynasty, but local Uyghur Buddhist rulers still held power until the invasion by the Moghul Khizr Khoja in 1389.

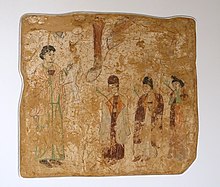

Turfan expeditions

[edit]German scientists conducted archaeological expeditions, known as the German Turfan expeditions, at the beginning of the 20th century (between 1902 and 1914). They discovered paintings and other art treasures that were transported to the Museum of Asian Art in Berlin.

Artifacts of Manichaean and Buddhist provenance were also found in Turfan.[34] During World War II, many of these artifacts were destroyed or looted.[35]

Turfan fragments

[edit]Uyghur, Persian, Sogdian and Syriac documents have been found in Turfan.[36] Turfan also has documents in Middle Persian.[37]

All these are known as the Turfan fragments. They comprise a collection of over 40,000 manuscripts and manuscript fragments in 16 different languages and 26 different typefaces in different book forms. They are in the custody of the Berlin State Library where their study continues.

These writings deal with Buddhist as well as Christian-Nestorian, Manichaean and secular contents. The approximately 8,000 Old Turkic Buddhist texts make up the largest part of this.

A whole series of Sogdian Buddhist scriptures were found in Turpan (and also in Dunhuang), but these date from the Tang dynasty (618–907) and are translations from Chinese. Earlier Sogdian Buddhist texts could not be found.

Christian texts exist mainly in Syriac and Sogdian, but also as Syriac-Sogdian bilinguals (bilingual texts), as well as some Turkish-Nestorian fragments. They include fragments of Sogdian translations of works by Isaac the Syrian.[38][39]

Manichaean texts survive in Middle Persian, Parthian, Sogdian and Uyghur; the Sogdian and Uyghur documents show a notable adaptation to Buddhism, but there is also evidence of a reverse influence.

Important parts of the Gospel of Mani were found here, for example. Also, parts of the Arzhang (Book of Pictures), one of the holy books of Manichaeism were discovered.

Most of the Buddhist texts survive in only fragmentary form. There are several Indian Sanskrit texts from various schools of Mahayana and Hinayana, Uyghur texts that are mostly translations from Sanskrit, Tocharian and, starting in the 9th century, increasingly from the Chinese.

Many of the Uyghur documents and fragments of Buddhist scriptures edited to date include didactic texts (sutras) and philosophical works (the abhidharma). In contrast to the other Buddhist contents, the monastic discipline texts (the vinaya) did not seem to be translated, but rather taught and studied in Sanskrit.[40]

Conversion to Islam

[edit]The conversion of the local Buddhist population to Islam was completed in the second half of the 15th century.[41]

After being converted, the descendants of the previously Buddhist Uyghurs in Turfan failed to retain memory of their ancestral legacy and falsely believed that the "infidel Kalmuks" (Dzungars) were the ones who built Buddhist monuments in their area.[42]

15th and 16th centuries

[edit]Buddhist images and temples in Turfan were described in 1414 by the Ming diplomat Chen Cheng.[43][44]

As late as 1420, the Timurid envoy Ghiyāth al-dīn Naqqāsh, who passed through Turpan on the way from Herat to Beijing, reported that many of the city's residents were "infidels". He visited a "very large and beautiful" temple with a statue of Shakyamuni; in one of the versions of his account it was also claimed that many Turpanians "worshipped the cross".[45]

The Moghul ruler of Turpan Yunus Khan, also known as Ḥājjī 'Ali (ruled 1462–1478), unified Moghulistan (roughly corresponding to today's Eastern Xinjiang) under his authority in 1472. Around that time, a conflict with the Ming China started over the issues of tribute trade: Turpanians benefited from sending "tribute missions" to China, which allowed them to receive valuable gifts from the Ming emperors and to do plenty of trading on the side; the Chinese, however, felt that receiving and entertaining these missions was just too expensive. (Muslim envoys to the early Ming China were impressed by the lavish reception offered to them along their route through China, from Suzhou to Beijing, such as described by Ghiyāth al-dīn Naqqāsh in 1420–1421.[47])

Yunus Khan was irritated by the restrictions on the frequency and size of Turpanian missions (no more than one mission in 5 years, with no more than 10 members) imposed by the Ming government in 1465 and by the Ming's refusal to bestow sufficiently luxurious gifts on his envoys (1469). Accordingly, in 1473 he went to war against China, and succeeded in capturing Hami in 1473 from the Oirat Mongol Henshen and holding it for a while, until Ali was repulsed by the Ming dynasty into Turfan. He reoccupied Hami after Ming left. Henshen's Mongols recaptured Hami twice in 1482 and 1483, but the son of Ali, Ahmad Alaq, who ruled Eastern Moghulistan or Turpan Khanate, reconquered it in 1493 and captured the Hami leader and the resident of China in Hami (Hami was a vassal state to Ming). In response, the Ming dynasty imposed an economic blockade on Turfan and kicked out all the Uyghurs from Gansu. It became so harsh for Turfan that Ahmed left. Ahmed's son Mansur succeeded him and took over Hami in 1517.[48][49] These conflicts were called the Ming–Turpan conflict.

Several times, after occupying Hami, Mansur tried to attack China in 1524 with 20,000 men, but was beaten by Chinese forces. The Turpan kingdom under Mansur, in alliance with Oirat Mongols, tried to raid Suzhou in Gansu in 1528, but were severely defeated by Ming Chinese forces and suffered heavy casualties.[50] The Chinese refused to lift the economic blockade and restrictions that had led to the battles and continued restricting Turpan's tribute and trade with China. Turfan also annexed Hami.[51]

18th and 19th centuries

[edit]The Imin mosque of Turfan was built in 1779.[52]

Francis Younghusband visited Turpan in 1887 on his overland journey from Beijing to India. He said it consisted of two walled towns, a Chinese one with a population of no more than 5,000 and, about a mile (1.6 km) to the west, a Turk town of "probably" 12,000 to 15,000 inhabitants. The town (presumably the "Turk town") had four gateways, one for each of the cardinal directions, of solid brickwork and massive wooden doors plated with iron and covered by a semicircular bastion. The well-kept walls were of mud and about 35 ft (10.7 m) tall and 20 to 30 feet (6 to 9 m) thick, with loopholes at the top. There was a level space about 15 yards (14 m) wide outside the main walls surrounded by a musketry wall about 8 ft (2.4 m) high, with a ditch around it some 12 ft (3.7 m) deep and 20 ft (6 m) wide. There were drumtowers over the gateways, small square towers at the corners and two small square bastions between the corners and the gateways, "two to each front". Wheat, cotton, poppies, melons and grapes were grown in the surrounding fields.[53]

Turpan grapes impressed other travelers to the region as well. The 19th-century Russian explorer Grigory Grum-Grshimailo, thought the local raisins may be "the best in the world" and noted the buildings of a "perfectly peculiar design" used for drying them called chunche.[54]

Mongols, Chinese and Chantos all lived in Turfan during this period.[55]

20th and 21st centuries

[edit]In 1931, a Uyghur rebellion broke out in the region, after a Chinese commander tried to forcibly marry a local girl.[56] The Chinese responded by indiscriminately attacking Muslims; this turned the entire countryside against the Chinese administration and the Uyghurs, Kazakhs, Kyrgyz and Tungans joined the rebels.[56]

On 19 August 1981, Deng Xiaoping conducted an inspection in Turpan Prefecture.[57]

On 31 March 1995, Turpan and Dunhuang became sister cities.[57]

According to reports from Radio Free Asia, as of 2020, there were eight Xinjiang internment camps in the prefecture.[58]

Geography

[edit]Subdivisions

[edit]Turpan directly controls one district and two counties.

| Map | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| # | Name | Chinese characters | Hanyu Pinyin | Uyghur (UEY) | Uyghur Latin (ULY) | Population (2020 Census) |

Area (km2) | Density (/km2) |

| 1 | Gaochang District | 高昌区 | Gāochāng Qū | قاراھوجا رايونى | Qarahoja Rayoni | 317,443 | 13,651 | 23.25 |

| 2 | Shanshan County | 鄯善县 | Shànshàn Xiàn | پىچان ناھىيىسى | Pichan Nahiyisi | 242,310 | 39,547 | 6.13 |

| 3 | Toksun County | 托克逊县 | Tuōkèxùn Xiàn | توقسۇن ناھىيىسى | Toqsun Nahiyisi | 134,235 | 16,561 | 8.11 |

Turpan is located about 150 km (93 mi) southeast of Ürümqi, Xinjiang's capital, in a mountain basin, on the northern side of the Turpan Depression, at an elevation of 30 m (98 ft) above sea level. Outside of Turpan is a small volcanic cone, the Turfan volcano, that is said to have erupted in 1120 as described in the Song dynasty.[59] In June 1995, a book of standard names for local geography was published.[57]

Climate

[edit]Turpan has an extremely continental desert climate (Köppen Climate Classification BWk), with long, extremely hot summers (resembling a hot desert climate or BWh) and somewhat short but very cold winters, with very brief spring and autumn in between. Annual precipitation is very low, amounting to only 15.7 millimetres (0.62 in). The monthly 24-hour average temperature ranges from −6.7 °C (19.9 °F) in January to 33.1 °C (91.6 °F) in July, or a very large seasonal variation of 39.8 °C (71.6 °F); the annual mean is 15.7 °C (60.3 °F).[60] With monthly percent possible sunshine ranging from 48% in December to 75% in September, sunshine is abundant and the city receives 2,912 hours of bright sunshine annually.

Extremes have ranged from −28.9 °C (−20 °F) to 49.1 °C (120 °F) with Sanbao to its east having recorded a national all time record high for China at 52.2 °C (126 °F),[61][62] although a reading of 49.6 °C (121 °F) in July 1975 is regarded as dubious.[63] However, the high heat and dryness of the summer, when combined with the area's ancient system of irrigation, allows the countryside around Turpan to produce great quantities of high-quality fruit.

| Climate data for Turpan, elevation 39 m (128 ft), (1991–2020 normals) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 8.5 (47.3) |

19.5 (67.1) |

31.7 (89.1) |

40.5 (104.9) |

43.6 (110.5) |

47.6 (117.7) |

49.1 (120.4) |

47.8 (118.0) |

43.4 (110.1) |

34.3 (93.7) |

23.0 (73.4) |

9.6 (49.3) |

49.1 (120.4) |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | −2.3 (27.9) |

7.0 (44.6) |

17.9 (64.2) |

27.8 (82.0) |

33.9 (93.0) |

38.8 (101.8) |

40.5 (104.9) |

39.0 (102.2) |

32.6 (90.7) |

22.5 (72.5) |

10.3 (50.5) |

−0.4 (31.3) |

22.3 (72.1) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | −6.7 (19.9) |

1.3 (34.3) |

11.6 (52.9) |

20.7 (69.3) |

26.6 (79.9) |

31.6 (88.9) |

33.1 (91.6) |

31.2 (88.2) |

24.6 (76.3) |

14.5 (58.1) |

4.4 (39.9) |

−4.4 (24.1) |

15.7 (60.3) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | −10.3 (13.5) |

−3.5 (25.7) |

5.9 (42.6) |

14.2 (57.6) |

19.8 (67.6) |

24.7 (76.5) |

26.5 (79.7) |

24.6 (76.3) |

18.4 (65.1) |

9.1 (48.4) |

0.3 (32.5) |

−7.6 (18.3) |

10.2 (50.3) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −28.9 (−20.0) |

−24.5 (−12.1) |

−10.4 (13.3) |

−1.8 (28.8) |

4.7 (40.5) |

11.5 (52.7) |

15.5 (59.9) |

11.6 (52.9) |

1.3 (34.3) |

−5.7 (21.7) |

−17.8 (0.0) |

−26.1 (−15.0) |

−28.9 (−20.0) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 0.9 (0.04) |

0.5 (0.02) |

0.7 (0.03) |

0.9 (0.04) |

1.0 (0.04) |

2.6 (0.10) |

2.0 (0.08) |

2.0 (0.08) |

1.4 (0.06) |

1.2 (0.05) |

0.6 (0.02) |

0.9 (0.04) |

14.7 (0.6) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 0.1 mm) | 1.0 | 0.3 | 0.3 | 0.7 | 1.1 | 2.0 | 2.3 | 1.9 | 0.9 | 0.8 | 0.5 | 1.1 | 12.9 |

| Average snowy days | 2.5 | 0.9 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.2 | 2.6 | 6.2 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 56 | 40 | 25 | 23 | 25 | 27 | 30 | 31 | 35 | 45 | 50 | 56 | 37 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 121.8 | 172.0 | 234.2 | 263.7 | 308.4 | 301.6 | 303.3 | 299.6 | 273.5 | 238.6 | 163.7 | 108.2 | 2,788.6 |

| Percent possible sunshine | 41 | 57 | 62 | 65 | 67 | 66 | 66 | 71 | 74 | 71 | 57 | 39 | 61 |

| Source 1: China Meteorological Administration[64][65][66] | |||||||||||||

| Source 2: [67] | |||||||||||||

| Climate data for Turpan (Dongkan Station), elevation −49 m (−161 ft), (1991–2020 normals) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | −1.9 (28.6) |

7.6 (45.7) |

18.6 (65.5) |

28.5 (83.3) |

34.5 (94.1) |

39.3 (102.7) |

40.8 (105.4) |

39.3 (102.7) |

33.2 (91.8) |

23.2 (73.8) |

10.9 (51.6) |

0.0 (32.0) |

22.8 (73.1) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | −8.0 (17.6) |

0.5 (32.9) |

11.1 (52.0) |

20.7 (69.3) |

26.8 (80.2) |

31.9 (89.4) |

33.3 (91.9) |

31.4 (88.5) |

24.8 (76.6) |

14.8 (58.6) |

3.8 (38.8) |

−5.7 (21.7) |

15.5 (59.8) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | −12.8 (9.0) |

−5.5 (22.1) |

4.5 (40.1) |

13.8 (56.8) |

19.7 (67.5) |

24.9 (76.8) |

26.6 (79.9) |

24.7 (76.5) |

18.3 (64.9) |

8.6 (47.5) |

−1.3 (29.7) |

−9.9 (14.2) |

9.3 (48.8) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 0.8 (0.03) |

0.4 (0.02) |

0.6 (0.02) |

1.0 (0.04) |

1.0 (0.04) |

2.5 (0.10) |

2.0 (0.08) |

1.9 (0.07) |

1.3 (0.05) |

0.9 (0.04) |

0.4 (0.02) |

0.6 (0.02) |

13.4 (0.53) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 0.1 mm) | 1.0 | 0.3 | 0.3 | 0.8 | 1.0 | 2.1 | 2.4 | 2.1 | 1.0 | 0.6 | 0.4 | 0.8 | 12.8 |

| Average snowy days | 2.2 | 0.6 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.1 | 2.0 | 4.9 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 56 | 41 | 26 | 24 | 25 | 28 | 32 | 33 | 34 | 41 | 48 | 57 | 37 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 161.9 | 193.2 | 246.9 | 267.1 | 307.9 | 304.8 | 306.1 | 302.3 | 282.0 | 254.7 | 186.0 | 140.0 | 2,952.9 |

| Percent possible sunshine | 55 | 64 | 66 | 66 | 67 | 67 | 67 | 71 | 77 | 76 | 65 | 50 | 66 |

| Source: China Meteorological Administration[64][68] | |||||||||||||

Demographics

[edit]According to the 2015 government census,[69] the city of Turpan had a population of 651,853 (population density 15.99 inh./km2). Islam is largest religion. The breakdown by ethnicity was as follows:

| 2000 | 2015 | 2018 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Language

[edit]There is Chinese influence in the vocabulary of Uyghur dialect in Turpan.[70]

Assimilation

[edit]Turpan Uyghurs have more Han Chinese features and looks than Uyghurs elsewhere and this is suggested to be due to intermarriage between Han Chinese and Uyghurs in the past according to the locals.[71] Due to physical features found in Uyghurs in Turpan it was claimed that Uyghurs married slaves sent to Turpan's Lukchun area by the Qing according to the Manchu Ji Dachun.[72][73]

Economy

[edit]

Turpan is an agricultural economy growing vegetables, cotton, and especially grapes being China's largest raisin producing area.[74] There is a steady increase in farming acreage devoted to grapes backed by strong local government support for increased production.[74] The local government has coordinated improvements in raisin distribution, offered preferential loans for grape cultivation, and free management training to growers.[74] The annual Turpan Grape festival includes a mass wedding of Uyghurs funded by the government.[75]

Transport

[edit]

Turpan is served by the Lanzhou–Xinjiang High-Speed Railway through the Turpan North Railway Station. Turpan Railway Station is the junction for two conventional lines, the Lanzhou-Xinjiang and the Southern Xinjiang Railways.

China National Highway 312 passes through Turpan.

The Tulufan Jiaohe Airport is close to Turpan North Railway Station.

Attractions

[edit]Turpan is home to one of several caves associated with the pious Christian and Muslim legend of the Seven Sleepers.[76]

Notable persons

[edit]See also

[edit]- Dingling (with a special section about the Fufuluo)

- German Turfan expeditions

- Grape Valley

- Jiaohe ruins

- Silk Road transmission of Buddhism

- Tarim mummies

- Turpan Karez Paradise

- Turpan Museum

- Turpan Khanate

- Death Valley

References

[edit]- ^ "伊犁州2019年国民经济和社会发展统计公报" (in Chinese). 12 March 2021. Retrieved 12 March 2021.

- ^ Svat Soucek (2000). A History of Inner Asia. Cambridge University Press. p. 17. ISBN 9780521657044.

- ^ Denis Sinor (1997). Inner Asia. RoutledgeCurzon. p. 121. ISBN 978-0-7007-0896-3.

- ^ Elizabeth Wayland Barber (2000). Mummies of Ürümchi. W. W. Norton, Incorporated. pp. 166–. ISBN 978-0-393-32019-0.

- ^ Hill (2009), p. 109.

- ^ Grousset, Rene (1970). The Empire of the Steppes. Rutgers University Press. pp. 35, 37, 42. ISBN 0-8135-1304-9.

- ^ Hill (2009), p. 442.

- ^ Baij Nath Puri (December 1987). Buddhism in Central Asia. Motilal Banarsidass. p. 70. ISBN 978-8120803725.

- ^ "Section 26 – The Kingdom of Nearer [i.e. Southern] Jushi 車師前 (Turfan)".

- ^ Valerie Hansen (2015). The Silk Road: A New History. Oxford University Press. pp. 83–. ISBN 978-0-19-021842-3.

- ^ Ahmad Hasan Dani, ed. (1999). History of civilizations of Central Asia, Volume 3. Motilal Banarsidass. p. 304. ISBN 81-208-1540-8. Retrieved 17 May 2011.

- ^ Society for the Study of Chinese Religions (U.S.), Indiana University, Bloomington. East Asian Studies Center (2002). Journal of Chinese religions, Issues 30-31. the University of California: Society for the Study of Chinese Religions. p. 24. Retrieved 17 May 2011.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Susan Whitfield; British Library (2004). The Silk Road: Trade, Travel, War and Faith. Serindia Publications, Inc. pp. 309–. ISBN 978-1-932476-13-2.

- ^ Ahmad Hasan Dani, ed. (1999). History of civilizations of Central Asia, Volume 3. Motilal Banarsidass. p. 305. ISBN 81-208-1540-8. Retrieved 17 May 2011.

- ^ Tatsurō Yamamoto, ed. (1984). Proceedings of the Thirty-First International Congress of Human Sciences in Asia and North Africa, Tokyo-Kyoto, 31st August-7th September 1983, Volume 2. Indiana University: Tōhō Gakkai. p. 997. Retrieved 17 May 2011.

- ^ Albert E. Dien; Jeffrey K. Riegel; Nancy Thompson Price (1985). Albert E. Dien; Jeffrey K. Riegel; Nancy Thompson Price (eds.). Chinese archaeological abstracts: post Han. Vol. 4 of Chinese Archaeological Abstracts. the University of Michigan: Institute of Archaeology, University of California, Los Angeles. p. 1567. ISBN 0-917956-54-0. Retrieved 17 May 2011.

- ^ Louis-Frédéric (1977). Encyclopaedia of Asian civilizations, Volume 3. the University of Michigan: L. Frédéric. p. 16. ISBN 978-2-902228-00-3. Retrieved 17 May 2011.

- ^ a b ROY ANDREW MILLER, ed. (1959). Accounts of Western Nations in the History of the Northern Chou Dynasty. Berkeley and Los Angeles: UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA PRESS. p. 5. Retrieved 17 May 2011.East Asia Studies Institute of International Studies University of California CHINESE DYNASTIC HISTORIES TRANSLATIONS No. 6

- ^ Ahmad Hasan Dani, ed. (1999). History of civilizations of Central Asia, Volume 3. Motilal Banarsidass. p. 306. ISBN 81-208-1540-8. Retrieved 17 May 2011.

- ^ Tōyō Bunko (Japan). Kenkyūbu (1974). Memoirs of the Research Department of the Toyo Bunko (the Oriental Library), Volumes 32-34. the University of Michigan: The Toyo Bunko. p. 107. Retrieved 17 May 2011.

- ^ Chang Kuan-ta (1996). Boris Anatol'evich Litvinskiĭ; Zhang, Guang-da; R. Shabani Samghabadi (eds.). The crossroads of civilizations: A.D. 250 to 750. UNESCO. p. 306. ISBN 92-3-103211-9. Retrieved 17 May 2011.

- ^ a b Rene Grousset (1991). The Empire of the Steppes:A History of Central Asia. Rutgers University Press. pp. 98–99. ISBN 0813513049.

- ^ a b c HANSEN, Valerie. "The Impact of the Silk Road Trade on a Local Community: The Turfan Oasis, 500–800" (PDF). Yale University Press. Archived from the original (PDF) on 18 April 2009. Retrieved 14 July 2010.

- ^ Xin Tangshu 221a:6230. In addition, Susan Whitfield offers a fictionalized account of a Kuchean courtesan's experiences in the 9th century without providing any sources, although she has clearly drawn on the description of the prostitutes' quarter in Chang’an in Beilizhi; Whitfield, 1999, pp. 138–154.

- ^ Wang, Y (1995). "A study on the migration policy in ancient China". Chin J Popul Sci. 7 (1): 27–38. PMID 12288967.

- ^ Wu Zhen 2000[full citation needed] (p. 154 is a Chinese-language rendering based on Yoshida's Japanese translation of the Sogdian contract of 639).

- ^ Rong Xinjiang, 2001, pp. 132–135. Of the 21 epitaphs, 12 are from Quan Tangwen buyi (supplement to the complete writings of the Tang), five from Tangdai muzhi huibian (Collected epitaphs of the Tang), three were excavated at Guyuan, Ningxia, and one is from another site.

- ^ Yan is a common ending for Sogdian first names meaning 'for the benefit of' a certain deity. For other examples, see Cai Hongsheng, 1998, p. 40.

- ^ Ikeda contract 29.

- ^ Ikeda contract 31. Yoshida Yutaka and Arakawa Masaharu saw this document, which was clearly a copy of the original with space left for the places where the seals appeared.

- ^ Jian Li; Valerie Hansen; Dayton Art Institute; Memphis Brooks Museum of Art (January 2003). The glory of the silk road: art from ancient China. The Dayton Art Institute. p. 35. ISBN 978-0-937809-24-2.

- ^ Valerie Hansen (11 October 2012). The Silk Road. OUP USA. pp. 11–. ISBN 978-0-19-515931-8.

- ^ "The Christian Library from Turfan". SOAS, University of London. Archived from the original on 14 August 2014. Retrieved 5 August 2014.

- ^ Zsuzsanna Gulácsi (2005). Mediaeval Manichaean Book Art: A Codicological Study of Iranian And Turkic Illuminated Book Fragments from 8th–11th Century East Central Asia. BRILL. pp. 19–. ISBN 90-04-13994-X.

- ^ From the Introduction by Peter Hopkirk in the 1985 edition of Von Le Coq's Buried Treasures of Chinese Turkestan, p. ix-x.

- ^ Li Tang; Dietmar W. Winkler (2013). From the Oxus River to the Chinese Shores: Studies on East Syriac Christianity in China and Central Asia. LIT Verlag Münster. pp. 365–. ISBN 978-3-643-90329-7.

- ^ Ludwig Paul (January 2003). Persian Origins--: Early Judaeo-Persian and the Emergence of New Persian : Collected Papers of the Symposium, Göttingen 1999. Otto Harrassowitz Verlag. pp. 1–. ISBN 978-3-447-04731-9.

- ^ Pirtea, Adrian (2019). "Isaac of Nineveh, Gnostic Chapters," in Nicholas Sims-Williams, From Liturgy to Pharmacology: Christian Sogdian Texts from the Turfan Collection. Berliner Turfantexte 45. Turnhout: Brepols, pp. 117-44. (K4.39 mid to 46 beginning; parts of ch. 1.84-85, K1.16, 19)

- ^ Sims-Williams, Nicholas (2017). An Ascetic Miscellany: The Christian Sogdian Manuscript E28. Turnhout: Brepols, pp. 19-43.

- ^ Turfan expeditions iranicaonline.org

- ^ 关于明代前期土鲁番统治者世系的几个问题. Chinese Academy of Social Sciences.[permanent dead link]

- ^ Hamilton Alexander Rosskeen Gibb; Bernard Lewis; Johannes Hendrik Kramers; Charles Pellat; Joseph Schacht (1998). The Encyclopaedia of Islam. Brill. p. 677.

- ^ Rossabi, M. 1972. "Ming China and Turfan, 1406–1517". Central Asiatic Journal 16 (3). Harrassowitz Verlag: 212.

- ^ Morris Rossabi (28 November 2014). From Yuan to Modern China and Mongolia: The Writings of Morris Rossabi. BRILL. pp. 45–. ISBN 978-90-04-28529-3.

- ^ Bellér-Hann, Ildikó (1995), A History of Cathay: a translation and linguistic analysis of a fifteenth-century Turkic manuscript, Bloomington: Indiana University, Research Institute for Inner Asian Studies, p. 159, ISBN 0-933070-37-3. Christianity is mentioned in the Turkic translation of Ghiyāth al-dīn's account published by Bellér-Hann, but not in the earlier Persian versions of his story.

- ^ Lach, Donald F. (Donald Frederick) (1965). Asia in the making of Europe. Chicago : University of Chicago Press. p. 238. ISBN 978-0-226-46733-7.

Nieuhof's report of a Mughul embassy to Peking was taken at face value by C. B. K. Roa Sahib, "Shah Jehan's Embassy to China, 1656 a.d.," Quarterly Journal of the Mythic Society, Silver Jubilee Number XXV (1934-35), 117-21. By examination of the Chinese sources, Luciano Petech concluded that Nieuhof was mistaken in this identification. He argues, quite convincingly, that these were probably emissaries from Turfan in central Asia. See Petech, "La pretesa ambascita di Shah Jahan alia Cina," Rivista degli studi orientali, XXVI (1951), 124-27.

- ^ Bellér-Hann 1995, pp. 160–175

- ^ Trudy Ring; Robert M. Salkin; Sharon La Boda (1996). International Dictionary of Historic Places: Asia and Oceania. Taylor & Francis. p. 323. ISBN 1-884964-04-4.

- ^ Goodrich & Fang 1976

- ^ Luther Carrington Goodrich; Chao-ying Fang (1976). Dictionary of Ming Biography, 1368–1644. Columbia University Press. p. 1038. ISBN 0-231-03833-X.

- ^ Jonathan D. Spence; John E. Wills Jr.; Jerry B. Dennerline (1979). From Ming to Ch'ing: Conquest, Region, and Continuity in Seventeenth-Century China. Yale University Press. p. 177. ISBN 0-300-02672-2.

- ^ Andrew Petersen. "China". Dictionary of Islamic Architecture. Routledge. p. 54.

- ^ Younghusband, Francis E. (1896). The Heart of a Continent, pp. 139–140. John Murray, London. Facsimile reprint: (2005) Elbiron Classics. ISBN 1-4212-6551-6 (pbk); ISBN 1-4212-6550-8 (hardcover).

- ^ Grigory Grum-Grshimailo (Г. Грум-Гржимайло), East Turkestan (Восточный Туркестан), in Brockhaus and Efron Encyclopedic Dictionary. (in Russian) (The original quote: «Турфан же славится и своим изюмом, который можно считать лучшим в мире (высушивается в совершенно своеобразного типа сушильнях))», i.e. "Turfan is also famous for its raisins, which may be deemed the best in the world. They are dried in drying houses of a completely peculiar type".

- ^ The Geographical Journal. Royal Geographical Society. 1907. pp. 266–.

- ^ a b S. Frederick Starr (ed.). Xinjiang: China's Muslim Borderland: China's Muslim Borderland. Routledge. p. 75.

- ^ a b c 柏晓 (吐鲁番地区地方志编委会), ed. (September 2004). 吐鲁番地区志 (in Simplified Chinese). Ürümqi: 新疆人民出版社. pp. 50, 64, 748. ISBN 7-228-09218-X.

- ^ Shohret Hoshur, Joshua Lipes (16 September 2020). "Detainees Endure Forced Labor in Xinjiang Region Where Disney Filmed Mulan". Radio Free Asia. Translated by Mamatjan Juma. Retrieved 19 September 2020.

- ^ "Turfan". Global Volcanism Program. Retrieved 21 August 2011.

- ^ "中国地面国际交换站气候标准值月值数据集(1971-2000年)" (in Simplified Chinese). China Meteorological Administration. Retrieved 3 April 2010.

- ^ "Resumen synop".

- ^ "China logs 52.2 Celsius as extreme weather rewrites records". Reuters. 17 July 2023. Retrieved 22 October 2024.

- ^ "Extreme Temperatures Around the World". Retrieved 28 August 2010.

- ^ a b 中国气象数据网 – WeatherBk Data (in Simplified Chinese). China Meteorological Administration. Retrieved 10 October 2023.

- ^ 中国气象数据网 (in Simplified Chinese). China Meteorological Administration. Retrieved 10 October 2023.

- ^ 中国地面国际交换站气候标准值月值数据集(1971-2000年). China Meteorological Administration. Archived from the original on 21 September 2013. Retrieved 25 May 2010.

- ^ "Extreme Temperatures Around the World". Retrieved 28 August 2010.

- ^ 中国气象数据网 (in Simplified Chinese). China Meteorological Administration. Retrieved 10 October 2023.

- ^ 新疆维吾尔自治区统计局 [Statistic Bureau of Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region]. 14 July 2017. Archived from the original on 11 October 2017. Retrieved 1 November 2017.

- ^ Abdurishid Yakup (2005). The Turfan Dialect of Uyghur. Otto Harrassowitz Verlag. p. 174. ISBN 978-3-447-05233-7.

- ^ Joanne N. Smith Finley (9 September 2013). The Art of Symbolic Resistance: Uyghur Identities and Uyghur-Han Relations in Contemporary Xinjiang. BRILL. p. 309. ISBN 978-90-04-25678-1.

- ^ Justin Jon Rudelson; Justin Ben-Adam Rudelson (1997). Oasis Identities: Uyghur Nationalism Along China's Silk Road. Columbia University Press. pp. 141–. ISBN 978-0-231-10786-0.

- ^ Justin Jon Rudelson; Justin Ben-Adam Rudelson (1997). Oasis Identities: Uyghur Nationalism Along China's Silk Road. Columbia University Press. pp. 141–. ISBN 978-0-231-10787-7.

- ^ a b c "China, People's Republic of Dried Fruit Annual 2007" (PDF). Global Agriculture Information Network. USDA Foreign Agricultural Service.

- ^ Summers, Josh (22 August 2014). "The Day I Ran Across a Mass Uyghur Wedding in Turpan". Far West China.

- ^ "Cave of Ashabe Kahf". Madain Project. Archived from the original on 7 July 2022. Retrieved 7 July 2022.

Further reading

[edit]- Goodrich, L. Carrington; Fang, Chaoying, eds. (1976), "Ḥājjī 'Ali", Dictionary of Ming Biography, 1368–1644. Volume I (A-L), Columbia University Press, pp. 479–481, ISBN 0-231-03801-1

- Hill, John E. (2009) Through the Jade Gate to Rome: A Study of the Silk Routes during the Later Han Dynasty, 1st to 2nd centuries CE. BookSurge, Charleston, South Carolina. ISBN 978-1-4392-2134-1.

- Hill, John E. 2004. The Peoples of the West from the Weilue 魏略 by Yu Huan 魚豢: A Third Century Chinese Account Composed between 239 and 265 CE. Draft annotated English translation.

- Hulsewé, A. F. P. and Loewe, M. A. N. 1979. China in Central Asia: The Early Stage 125 BC – AD 23: an annotated translation of chapters 61 and 96 of the History of the Former Han Dynasty. E. J. Brill, Leiden.

- Puri, B. N. Buddhism in Central Asia, Motilal Banarsidass Publishers Private Limited, Delhi, 1987. (2000 reprint).

- Rossabi, M. 1972. "Ming China and Turfan, 1406–1517". Central Asiatic Journal 16 (3). Harrassowitz Verlag: 206–25.

- Morris Rossabi (28 November 2014). "Ming China and Turfan 1406–1517". From Yuan to Modern China and Mongolia: The Writings of Morris Rossabi. BRILL. pp. 39–. ISBN 978-90-04-28529-3.

- Stein, Aurel M. 1912. Ruins of Desert Cathay: Personal narrative of explorations in Central Asia and westernmost China, 2 vols. Reprint: Delhi. Low Price Publications. 1990.

- Stein, Aurel M. 1921. Serindia: Detailed report of explorations in Central Asia and westernmost China, 5 vols. London & Oxford. Clarendon Press. Reprint: Delhi. Motilal Banarsidass. 1980.

- Stein Aurel M. 1928. Innermost Asia: Detailed report of explorations in Central Asia, Kan-su and Eastern Iran, 5 vols. Clarendon Press. Reprint: New Delhi. Cosmo Publications. 1981.

- Yu, Taishan. 2004. A History of the Relationships between the Western and Eastern Han, Wei, Jin, Northern and Southern Dynasties and the Western Regions. Sino-Platonic Papers No. 131 March 2004. Dept. of East Asian Languages and Civilizations, University of Pennsylvania.

External links

[edit]- Along the ancient silk routes: Central Asian art from the West Berlin State Museums, an exhibition catalog from The Metropolitan Museum of Art (fully available online as PDF), which contains material from Turpan

- Silk Road Seattle – University of Washington (The Silk Road Seattle website contains many useful resources including a number of full-text historical works, maps, photos, etc.)

- Karez (Qanats) of Turpan, China

- Images and travel impressions along the Silk Road – Turpan PPS in Spanish