Tower 42

| Tower 42 | |

|---|---|

Tower 42 looking north from Bishopsgate in May 2011 | |

| |

| Former names | NatWest Tower; International Financial Centre |

| Record height | |

| Tallest in the United Kingdom from 1980 to 1991[I] | |

| Preceded by | BT Tower |

| Surpassed by | One Canada Square |

| General information | |

| Type | Commercial |

| Location | 25 Old Broad Street, London |

| Coordinates | 51°30′55″N 0°05′02″W / 51.51528°N 0.08389°W |

| Construction started | 1971 |

| Completed | 1980 |

| Height | |

| Roof | 183 metres (600 ft) |

| Technical details | |

| Floor count | 47 |

| Floor area | 30,100 m2 (324,000 sq ft)[1] |

| Lifts/elevators | 21 |

| Design and construction | |

| Architect(s) | R Seifert & Partners |

| Structural engineer | Pell Frischmann |

| Main contractor | John Mowlem & Co |

| Website | |

| http://www.tower42.com/ | |

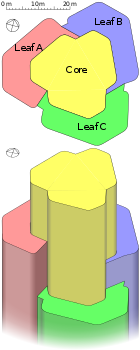

Tower 42, commonly known as the NatWest Tower, is a 183-metre-tall (600 ft) skyscraper in the City of London. It is the sixth-tallest tower in the City of London and the 19th-tallest in London overall.[2] Its original name was the National Westminster Tower, having been built to house NatWest's international headquarters. Seen from above, the shape of the tower resembles that of the NatWest logo (three chevrons in a hexagonal arrangement).[3]

The tower, designed by Richard Seifert and engineered by Pell Frischmann, is located at 25 Old Broad Street in the ward of Cornhill. It was built by John Mowlem & Co between 1971 and 1980, first occupied in 1980, and formally opened on 11 June 1981 by Queen Elizabeth II.[4]

At 183 metres (600 ft) high, it was the tallest building in the United Kingdom until superseded by One Canada Square at Canary Wharf in 1990. It was the tallest building built in London in the 1980s and remained the tallest in the City of London until overtaken by the 230-metre (750 ft) Heron Tower in 2010.

The building today is multi-tenanted and comprises Grade A office space and restaurant facilities, with restaurants on the 24th and 42nd floors.[5] In 2011, it was bought by the South African businessman Nathan Kirsh.

History

[edit]Design and development

[edit]

The National Westminster Tower's status as the first skyscraper in the city was a coup for NatWest, but was extremely controversial at the time, as it was a major departure from the previous restrictions on tall buildings in London. The original concept dates back to the early 1960s, predating the formation of the National Westminster Bank. The site was then the headquarters of the National Provincial Bank, with offices in Old Broad Street backing onto its flagship branch at 15 Bishopsgate.

Early designs envisaged a tower of 137 metres (449 ft); this developed into a design with a 197-metre (646 ft) tower as its centrepiece, proposed in 1964 by architect Richard Seifert. The plan attracted opposition, partly because of the unprecedented height of the design and partly because of the proposed demolition of the 19th-century bank building at 15 Bishopsgate, which dated from 1865 and was designed by architect John Gibson. Seifert, who had developed a reputation for overcoming planning objections, organised an exhibition in which he presented two alternative visions: his preferred design, and a second design featuring a 500-foot (150 m) tower with an "absurdly squat" second tower alongside. Visitors were invited to vote and overwhelmingly chose the single tower design.[8] The final design preserved the Gibson banking hall and the tower's height was reduced to 183 metres (600 ft).

Construction

[edit]

Demolition of the site commenced in 1970 and the tower was completed in 1980. The building was constructed by John Mowlem & Co[9] around a huge concrete core from which the floors are cantilevered, giving it great strength but significantly limiting the amount of office space available.

In total, there are 47 levels above ground, of which 42 are cantilevered. The lowest cantilevered floor is designated Level 1, but is in fact the fourth level above ground. The cantilevered floors are designed as three segments, or leaves, which approximately correspond to the three chevrons of the NatWest logo when viewed in plan. The two lowest cantilevered levels (1 and 2) are formed of a single "leaf"; and the next two (3 and 4) are formed of two leaves. This pattern is repeated at the top, so that only levels 5 to 38 extend around the whole of the building.

The limitations of the design were immediately apparent - even though the building opened six years before Big Bang, and so there was less of a requirement for large trading floors, the bank decided not to locate its foreign exchange and money market trading operation ("World Money Centre") in the tower; the unit remained in its existing location at 53 Threadneedle Street. Other international banking units, such as International Westminster Bank's London Branch and the Nostro Reconciliations Department remained at their locations (at 41 Threadneedle Street and Park House, Finsbury Square, respectively) due to lack of space in the tower.

Innovative features in the design included double-decked lifts, which provide an express service between the ground/mezzanine levels and the sky lobbies at levels 23 and 24. Double-decked lifts and sky lobbies were both new to the UK at the time. Other innovative features included an internal automated "mail train" used for mail deliveries and document distribution; an automated external window washing system; and computer controlled air conditioning. The tower also had its own telephone exchange in one of the basement levels – this area was decorated with panoramic photographs of the London skyline, creating the illusion of being above ground.[10]

Fire suppression design features included pressurised stairwells, smoke venting and fire retardant floor barriers. However, at the time of design, fire sprinkler systems were not mandatory in the UK and so were not installed.[10]

The cantilever is constructed to take advantage of the air rights granted to it and the neighbouring site whilst respecting the banking hall on that adjacent site, as only one building was allowed to be developed. For a time it was the tallest cantilever in the world.

Ownership

[edit]Following NatWest's refurbishment of the tower, the bank renamed it the International Finance Centre, in 1997.[11] The building was subsequently acquired by Hermes Real Estate and BlackRock's UK property fund in 1998 for £226 million.[12] In 2010 they put the property on the market at an expected price of £300 million. This would potentially have been the largest single commercial property sale in the City of London in 2010.[13] In July 2010 it was reported that Chinese Estates Group had entered exclusive discussions to buy Tower 42.[14] but this deal did not conclude and it was sold in 2011 to South African businessman Nathan Kirsh for £282.5 million.[15]

Occupancy

[edit]NatWest occupation

[edit]

Upon completion, the tower was occupied by a large part of NatWest's International Division. The upper floors were occupied by the division's executive management, marketing, and regional offices, moving from various locations in the City of London. The lower floors were occupied by NatWest's Overseas Branch, moving from its previous location at 52/53 Threadneedle Street.

The adjacent annexe building at 27 Old Broad Street was occupied by NatWest's Overseas Branch cashiers and foreign notes and coin dealing operation.

1993 bombing and refurbishment

[edit]

In 1993, NatWest had planned a major premises relocation that would have seen the International Banking Division move from the tower and be replaced with its Domestic Banking Division, enabling the bank to terminate its lease of the Drapers Gardens tower. These plans had to be abandoned after the tower was damaged in the April 1993 Bishopsgate bombing, a Provisional Irish Republican Army truck bombing in the Bishopsgate area of the City of London. The bomb killed one person and extensively damaged the tower and many other buildings in the vicinity, causing a total of over £1 billion worth of damage to the area.[16] The tower suffered severe damage and had to be entirely reclad and internally refurbished at a cost of £75 million.[17] (Demolition was considered, but would have been too difficult and expensive.)[18] The external re-clad was carried out by Alternative Access Logistics with the use of a multi-deck space frame system to access three floors at once with the ability to move up and down the whole building.[19]

On 17 January 1996, during the repairs and possibly from the welding being undertaken, a fire started at the top of the building.[20] Five hundred workmen were evacuated and smoke was seen coming out of the top of the building.[20] A helicopter using thermal imaging equipment pinpointed the source of the fire, which was on the 45th floor in a glass-fibre cooling tower.[20] After refurbishment, NatWest decided not to re-occupy and renamed the building the International Financial Centre, then sold it in 1998 to UK property company Greycoat, who renamed it Tower 42,[21] a reference to its 42 cantilevered floors. It is now a general-purpose office building.

Lighting display

[edit]

In June 2012, a Capix LED multi-media lighting system was installed around levels 39 to 45. This replaced the previous high-energy floodlighting at the top of the building. The lighting system forms thousands of pixels mounted on a chain netting that is affixed to the surface of the building. Each pixel is formed of three RGB LED units, allowing a variety of lighting designs and colours to be displayed. The system was designed by SVM Associates and Zumtobel.[22][23]

The display featured the Olympic Rings during the London 2012 Olympic Games and the Paralympic Agitos during the London 2012 Paralympic Games.[citation needed]

Ranking among London high-rise buildings

[edit]The National Westminster Tower was the tallest building in London and the United Kingdom for 10 years. At its completion in 1980, it claimed this title from the 177-metre (581 ft) 189-metre (620 ft) with antenna Post Office Tower, a transmission tower located in Fitzrovia.

By 2022, Tower 42 was the sixth-tallest tower in the City of London, and the 18th-tallest in London overall.[24]

Previous buildings on the site

[edit]- Gresham House, built in 1563 by Sir Thomas Gresham. Gresham was a businessman who helped set up the Royal Exchange. Upon the death of his wife in 1596, Gresham House became the 'Institute for Physic, Civil Law, Music, Astronomy, Geometry and Rhetoric', as directed by Gresham's will (Sir Thomas died 17 years earlier). Professors at Gresham College, described as the Third University of England by Chief Justice Coke in 1612, included Robert Hooke, Sir Christopher Wren and the composer John Bull. The building survived the Great Fire Of London, and saw use as a garrison, a Guildhall and Royal exchange. The College moved to Gresham Street. Gresham House was demolished in 1768 and a new Gresham House was built in its place.

- Crosby Hall, built in 1466 and named after its builder, the London merchant and alderman, Sir John Crosby. Its most famous occupant was King Richard III. A famous visitor was William Shakespeare. A scene of his play, Richard III, in which the future Richard III, then Duke of Gloucester, plots his route to the crown, is set in Crosby Hall.

- Crosby Place, which was built in 1596, the year that Richard III was written.[citation needed]

- Palmerston House was a building that survived from the 19th century, through both world wars. It was named after the Third Viscount Palmerston. It stood at 51-55 Broad Street. It was occupied for some time by the Cunard Steam Shipping Company.

Events

[edit]An annual charity fundraising event called Vertical Rush takes place inside Tower 42. It is a vertical run of 932 steps to the top of the tower.[25][26] The 2024 event, raising money for Shelter, took place on 28 February.[25]

Notes

[edit]- ^ "Tower 42". Skyscraper Center. CTBUH. Retrieved 18 October 2017.

- ^ "Home | CTBUH Skyscraper Center". Buildingdb.ctbuh.org. Retrieved 20 August 2012.

- ^ Hibbert, Christopher; Weinreb, Ben; Keay, John; Keay, Julia (2011). The London Encyclopaedia (3rd ed.). Pan Macmillan. p. 574. ISBN 9780230738782. Retrieved 20 August 2014.

- ^ Anne's baby to be called Miss Zara Glasgow Herald 12 June 1981 page 1

- ^ "Rent Office Space in Tower 42, City of London | the Search Office Space Blog | Searchofficespace". Archived from the original on 9 June 2011. Retrieved 7 February 2016.

- ^ "The Notorious Work of Richard Seifert". building.co.uk. Retrieved 21 August 2014. (subscription required)

- ^ London's Growing Up!: NLA Insight Study (PDF). New London Architecture. 2014. p. 44. ISBN 978-0-9927189-1-6. Archived from the original (PDF) on 21 August 2014. Retrieved 21 August 2014.

- ^ "Richard Seifert". The Daily Telegraph. London. 29 October 2001.

- ^ Mowlem dives into the red Evening Standard 4 February 2005

- ^ a b Building innovation reaches the sky, New Scientist 18 January 1979

- ^ "NatWest could sell tower". The Independent. 23 March 1998. Retrieved 20 August 2014.

- ^ Goodway, Nick (15 April 2010). "Outdated and second best, its time for the fall of Tower 42". Evening Standard. Retrieved 20 August 2014.

- ^ "Tower 42 skyscraper on market for £300m". Thisislondon.co.uk. 13 April 2010. Archived from the original on 5 June 2011. Retrieved 20 August 2012.

- ^ Marion Dakers (5 July 2010). "Chinese firm in exclusive talks to acquire Tower 42". City AM. Retrieved 20 August 2012.

- ^ South African tycoon Nathan Kirsh buys Tower 42 Daily Telegraph 21 December 2011

- ^ De Baróid, Ciarán (2000). Ballymurphy and the Irish War. Pluto Press. p. 325. ISBN 0-7453-1509-7.

- ^ Nick Goodway (15 April 2010). "Outdated and second best, its time for the fall of Tower 42". Evening Standard. Retrieved 20 August 2012.

- ^ Terminal Architecture, page 59, Martin Pawley, 1998, Reaktion Books (ISBN 1861890184)

- ^ "The Natwest Tower, London - Multi-deck space frame system". Alternative Access Logistics Ltd. Archived from the original on 7 July 2011. Retrieved 16 April 2010.

- ^ a b c "500 workmen escape NatWest Tower blaze", The Independent, 18 January 1996. Retrieved 19 September 2010

- ^ "Tower 42 Estate". greycoat.com.

- ^ "Tower 42 Olympic LED Lighting". Archived from the original on 11 October 2012. Retrieved 25 September 2012.

- ^ "CAPIX" (PDF). Zumtobel Group. Retrieved 28 September 2022.

- ^ "Home | CTBUH Skyscraper Center". Buildingdb.ctbuh.org. Retrieved 20 August 2012.

- ^ a b "Vertical Rush". shelter.org.uk. Retrieved 29 February 2024.

- ^ Hollingshead, Iain (21 February 2011). "Could you run a vertical marathon?". The Daily Telegraph.

External links

[edit]![]() Media related to Tower 42 at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Tower 42 at Wikimedia Commons