The Bible in film

| Part of a series on |

| Christianity |

|---|

|

Stories from the Bible have frequently been used in films. There are various reasons for motion picture producers to turn to the Bible as source material. The stories, in the public domain, are already familiar to potential audiences. They contain sweeping, but relatively straightforward, narratives of good versus evil, and feature crowd-pleasing battles, sword fights, natural disasters, and miracles.

History

[edit]The American film industry has been producing movies based on Bible stories since 1897: The Horitz Passion Play (1897) was the first Passion play to be shown in the United States.[1] One of the earliest biblical films was the 1903 production of Samson and Delilah, produced by the French company Pathé. Another early film about a story in the Book of Genesis was the 1904 French film Joseph Vendu Par Ses Frères (Joseph Sold by his Brothers).

Peak years for production of Biblical movies were around 1910. Matthew Page points out that "more biblical films were released in the years from 1909 to 1911 than at any other time".[2] Enrico Guazzoni's 1913 Italian epic Quo Vadis? is often considered the first successful feature-length motion picture and one of the first films with over two hours running time.[3] Cecil B. DeMille specialized in extravagant epics throughout a career that spanned both the silent and sound eras. His 1923 silent version of The Ten Commandments (1923) included spectacular special effects for the parting of the Red Sea. De Mille followed The Ten Commandments in 1927 with King of Kings, a lavish, reverential life of Christ with a climactic resurrection scene in color. King of Kings was re-released in 1931 with a synchronized musical score.[3]

MGM's 1925 silent-era Ben-Hur: A Tale of the Christ, starring Ramon Novarro was the most expensive film of its time. It included two spectacular scenes: the sea galley battle with pirates and the famous chariot-race.[3] Another "swords and sandals" epic of the 1920s was Noah's Ark which combined title cards with spoken dialogue.

The major studios produced fewer epics during the 1940s due in part to wartime scarcity of resources. After the war, some of Hollywood's highest grossing films were religious epics produced as vehicles for its biggest stars.[4] Samson and Delilah was the biggest moneymaking movie of 1949 and is considered the picture that sparked the biblical-epic film craze of the 1950s.[5] It was followed by two of 1951’s biggest box-office hits, Quo Vadis and David and Bathsheba. Charlton Heston starred in Cecil B. DeMille's The Ten Commandments and William Wyler's Ben-Hur.

According to author Diane Apostolos-Cappadona, in the 1950s and 1960s, during the era of the production code, "the most acceptable cinematic path for movies to incorporate sex and violence was the biblical epic".[6] Basing a film on the Bible allowed it to be more risqué than would normally have been accepted. Figures like Eve, Delilah, Jezebel and Judith could all be portrayed as seductive temptresses. In tales such as Sodom and Gomorrah and Samson and Delilah, exotic sins could be lavishly portrayed on screen. In his autobiography, DeMille wrote, "I am sometimes accused of gingering up the Bible with large and lavish infusions of sex and violence. I can only wonder if my accusers have ever read certain parts of the Bible."[7]

By the 1950s movies had to compete with television and became more colorful and bigger in story and scope. In 1953, CinemaScope was introduced in The Robe. In 1956 DeMille remade his 1923 film The Ten Commandments. It was the biggest moneymaker of 1956, nominated for seven Academy Awards, and won one for special effects.[5]

Professor Drew Casper, a film historian at the University of Southern California, says that by the mid-1960s several epic-style biblical movies flopped, and were partially blamed for the movie industry's financial troubles at that time. Two major studio attempts to make a film of Jesus' life during this period, The Greatest Story Ever Told and King of Kings were both commercial failures. The Greatest Story Ever Told (1965) cost $20 million, and recouped only $1.2 million.[4] With the end of the studio system and the changing social climate, the Bible epic film fell out of favour.

Mel Gibson's controversial The Passion of the Christ (2004), an interpretation of the last 12 hours in the life of Jesus, was extremely profitable, grossing $370 million (domestic). Due to dialogue in Hebrew and Aramaic, it was subtitled. It set a record for the highest-grossing independent film of all time.[8]

Old Testament/Hebrew Bible

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (November 2013) |

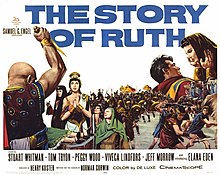

It has long been more popular to make films about the Old Testament/Hebrew Bible, than of the New Testament/Christian Bible. Old Testament stories are well suited for epic films. There have been over 100 films based on the Old Testament. These movies were made in great numbers both by Hollywood and the Italian film industry, and many of the biggest films were joint American/Italian productions. During this period most of the major stories in the Old Testament were put on film, some multiple times. Epics such as Sodom and Gomorrah, The Story of Ruth, David and Goliath, Solomon and Sheba, and Esther and the King dominated the box office.

In 1966, 20th Century Fox and Italian producer Dino DeLaurentiis made the first attempt to produce a series of films based on the entire Bible from Genesis to Revelation. The Bible: In the Beginning, based largely on the book of Genesis, was to have been the first of these films, but financial challenges cancelled further films. Forty-seven years later, Hearst Corporation and producers Roma Downey and Mark Burnett created their own reimagining of the story via a TV miniseries, The Bible, thus finally fulfilling DeLaurentiis' original 1966 vision.

The box office failure King David, was released in 1985.

New Testament/Christian Bible

[edit]This section is written like a personal reflection, personal essay, or argumentative essay that states a Wikipedia editor's personal feelings or presents an original argument about a topic. (November 2013) |

The New Testament was less frequently turned into major motion pictures. Unlike the Old Testament, the New Testament has few action scenes and little romance. During the 1950s, most of the films recounting Jesus' life were financed by church groups and played in churches. These were often film versions of the traditional Passion Play. At this time there were some successful films that involved Jesus, but they put him at a distance from the central characters and were based on novels rather than the Bible. These included the sequel to 1953's The Robe, Demetrius and the Gladiators (1954), and the 1959 remake film Ben-Hur.

In 1966, Pier Paolo Pasolini filmed The Gospel According to St. Matthew in southern Italy with a cast of non-professional actors. Despite Pasolini's atheism and Marxism, the film was praised by the Pope for its faithfulness. The revisionist The Last Temptation of Christ, the rock opera Jesus Christ Superstar, and the parody Life of Brian were all major films of the 1970s and 1980s. These films generated controversy, but were financially successful. Film versions of the Book of Revelation such as The Late Great Planet Earth and The Seventh Sign were made, which had been uncommon in an earlier era.

During this period more reverent works were produced, but often appeared as television miniseries or released directly to video. The success of The Passion of the Christ led to new Bible films being commissioned including Mary, Son of Man, Color of the Cross, The Ten Commandments, and Nativity, all of which were scheduled for a 2006 release.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ W. Barnes Tatum, Jesus at the Movies: A Guide to the First Hundred Years, Polebridge Press, 2004, p. 3.

- ^ Page, Matthew. 100 Bible Films, BFI, 2022, p.2.

- ^ a b c "Epics-Historical Films", AMC

- ^ a b Orden, Erika. "Hollywood's New Bible Stories", Wall Street Journal, September 27, 2012

- ^ a b Hicks, Chris. Samson and Delilah was start of biblical-epic film craze", Deseret News, March 7, 2013

- ^ Apostolos-Cappadona, Diane. "Review of Hallbäck and Hvithamar's 'The Bible in Contemporary Cinema', Review of Biblical Literature, Society of Biblical Literature, October 25, 2009

- ^ "Samson and Delilah: a good effort at biblical sex and violence", The Guardian, June 20, 2013

- ^ Dirks, Tim. "The History of Film", AMC