Troodon

| Troodon | |

|---|---|

| |

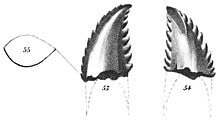

| Holotype tooth in multiple views | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Clade: | Dinosauria |

| Clade: | Saurischia |

| Clade: | Theropoda |

| Family: | †Troodontidae |

| Subfamily: | †Troodontinae |

| Genus: | †Troodon Leidy, 1856 |

| Type species | |

| †Troodon formosus Leidy, 1856p

| |

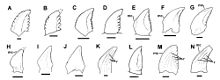

Troodon (/ˈtroʊ.ədɒn/ TROH-ə-don; Troödon in older sources) is a former wastebasket taxon and a potentially dubious genus of relatively small, bird-like theropod dinosaurs definitively known from the Campanian age of the Late Cretaceous period (about 77 mya). It includes at least one species, Troodon formosus, known from Montana. Discovered in October 1855, T. formosus was among the first dinosaurs found in North America, although it was thought to be a lizard until 1877. Several well-known troodontid specimens from the Dinosaur Park Formation in Alberta were once believed to be members of this genus. However, recent analyses in 2017 have found this genus to be undiagnostic and referred some of these specimens to the genus Stenonychosaurus (long believed to be synonymous with Troodon) some to the genus Latenivenatrix, and some to the genus Pectinodon. The genus name is Ancient Greek for "wounding tooth", referring to the teeth, which were different from those of most other theropods known at the time of their discovery. The teeth bear prominent, apically oriented serrations. These "wounding" serrations, however, are morphometrically more similar to those of herbivorous reptiles, and suggest a possibly omnivorous diet.[1]

History of discovery

[edit]Early research

[edit]

The name was originally spelled Troödon (with a diaeresis) by Joseph Leidy in 1856, which was officially amended to its current status by Sauvage in 1876.[2] The type specimen of Troodon has caused problems with classification, as the entire genus is based only on one single tooth from the Judith River Formation. Troodon has historically been a highly unstable classification and has been the subject of numerous conflicting synonymies with similar theropod specimens.[3]

The Troodon tooth was originally classified as a "lacertilian" (lizard) by Leidy, but reassigned as a megalosaurid dinosaur by Franz Nopcsa von Felső-Szilvás in 1901 (Megalosauridae having historically been a wastebin taxon for most carnivorous dinosaurs). In 1924, Gilmore suggested that the tooth belonged to the herbivorous pachycephalosaur Stegoceras and that Stegoceras was in fact a junior synonym of Troodon. The similarity of troodontid teeth to those of herbivorous dinosaurs continues to lead many paleontologists to believe that these animals were omnivores. The classification of Troodon as a pachycephalosaur was followed for many years, during which time the family Pachycephalosauridae was known as Troodontidae. In 1945, Charles Mortram Sternberg rejected the possibility that Troodon was a pachycephalosaur thanks to its stronger similarity to the teeth of other carnivorous dinosaurs. With Troodon now classified as a theropod, the family Troodontidae could no longer be used for the dome-headed dinosaurs, so Sternberg named a new family for them, Pachycephalosauridae.[4]

Naming of related species

[edit]

The first specimens assigned to Troodon that were not teeth were both found by Sternberg in the early 1930s in the Dinosaur Park Formation of Alberta. The first was named Stenonychosaurus inequalis by Sternberg in 1932 based on a foot, fragments of a hand, and some tail vertebrae. A remarkable feature of these remains was the enlarged claw on the second toe, which is now recognized as characteristic of early paravians. Sternberg initially classified Stenonychosaurus as a member of the family Coeluridae. The second, a partial lower jaw bone, was described by Gilmore (1932) as a new species of lizard which he named Polyodontosaurus grandis. In 1951, Sternberg later recognized P. grandis as a possible synonym of Troodon and speculated that, since Stenonychosaurus had a "very peculiar pes" and Troodon "equally unusual teeth", they may be closely related. Unfortunately, no comparable specimens were available at that time to test the idea. In a recent revision of the material by van der Reest & Currie, Polyodontosaurus was determined to be a nomen dubium, not fit for synonymy with other taxa.[5]

A more complete skeleton of Stenonychosaurus was described by Dale Russell in 1969 from the Dinosaur Park Formation, which eventually formed the scientific foundation for a famous life-sized sculpture of Stenonychosaurus accompanied by its fictional, humanoid descendant, the "dinosauroid".[6] Stenonychosaurus became a well-known theropod in the 1980s, when the feet and braincase were described in more detail. Along with Saurornithoides, it formed the family Saurornithoididae. Based on differences in tooth structure and the extremely fragmentary nature of the original Troodon formosus specimens, saurornithoidids were thought to be close relatives, while Troodon was considered a dubious possible relative of the family. Phil Currie, reviewing the pertinent specimens in 1987, showed that supposed differences in tooth and jaw structure among troodontids and saurornithoidids were based on age and position of the tooth in the jaw, rather than a difference in species. He reclassified Stenonychosaurus inequalis, Polyodontosaurus grandis, and Pectinodon bakkeri as junior synonyms of Troodon formosus. Currie also made Saurornithoididae a junior synonym of Troodontidae.[7] In 1988, Gregory S. Paul went farther and included Saurornithoides mongoliensis in the genus Troodon as T. mongoliensis,[8] but this reclassification, along with many other unilateral synonymizations of well known genera, was not adopted by other researchers. Currie's classification of all North American troodontid material in the single species Troodon formosus became widely adopted by other paleontologists and all of the specimens once called Stenonychosaurus were referred to as Troodon in scientific literature through the early 21st century.

Dissolution of the one species model

[edit]

However, the concept that all Late Cretaceous North American troodontids belong to one single species began to be questioned soon after Currie's 1987 paper was published, including by Currie himself. Currie and colleagues (1990) noted that, while they believed the Judith River troodontids were all T. formosus, troodontid fossils from other formations, such as the Hell Creek Formation and Lance Formation, might belong to different species. In 1991, George Olshevsky assigned the Lance formation fossils, which had first been named Pectinodon bakkeri, but later synonymized with Troodon formosus, to the species Troodon bakkeri, and several other researchers (including Currie) have reverted to keeping the Dinosaur Park Formation fossils separate as Troodon inequalis (now Stenonychosaurus inequalis).[9]

In 2011, Zanno and colleagues reviewed the convoluted history of troodontid classification in Late Cretaceous North America. They followed Longrich (2008) in treating Pectinodon bakkeri as a valid genus and noted that it is likely the numerous Late Cretaceous specimens currently assigned to Troodon formosus, but that a more thorough review of the specimens is required. Because the holotype of T. formosus is a single tooth, this renders Troodon a nomen dubium.[3]

In 2017, Evans and colleagues further discussed the undiagnostic nature of the holotype of Troodon formosus and suggested that Stenonychosaurus be used for troodontid skeletal material from the Dinosaur Park Formation.[10] Later in the same year, Aaron J. van der Reest and Currie came to a similar conclusion as Evans and colleagues and also split much of the material assigned to Stenonychosaurus into a new genus: Latenivenatrix.[5] In 2018, Varricchio and colleagues disagreed with Evans and colleagues, citing that Stenonychosaurus had not been used in the thirty years since Currie and colleagues synonymized it with Troodon and they indicated that "Troodon formosus remains the proper name for this taxon".[11] This conclusion by Varricchio was agreed upon by Sellés and colleagues in their 2021 description of Tamarro.[12] Varricchio's comments were later addressed by Cullen and colleagues in their 2021 review of Dinosaur Park Formation biodiversity, where they noted that, while Stenonychosaurus has indeed not been used for 30 years, Currie's original hypothesis of subjective synonymy (based on tooth and jaw morphology) was never directly tested and, given that later research found that teeth were not diagnostic below the family level in troodontids, Currie's original hypothesis is therefore not supported by the available data, regardless of the amount of time since it was originally proposed.[13] They suggested that the description of more complete skeletal material (i.e. containing dental, frontal, and postcranial elements) that can be tied to the holotype could allow the direct testing of the synonymy hypothesis, but re-affirmed that, for now, given the lack of supporting evidence, the synonymy of Troodon and Stenonychosaurus cannot be maintained and that merely remaining untested for 30 years is insufficient justification to accept a proposed lumping of taxa lacking overlapping diagnostic materials.[13] However, Varricchio and others still insist on their naming method.

Classification

[edit]

Troodon is considered to be one of the most derived members of its family. Along with Zanabazar, Saurornithoides, and Talos, it forms a clade of specialized troodontids.[3]

Below is a cladogram of Troodontidae by Zanno et al. in 2011.[3]

| Troodontidae |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Paleobiology

[edit]

One study was based on multiple Troodon teeth that have been collected from Late Cretaceous deposits in northern Alaska. These teeth are much larger than those collected from more southern sites, providing evidence that northern Alaskan populations of Troodon grew to larger average body size, hinting at Bergmann's rule. This study also provides an analysis of the proportions and wear patterns of a large sample of Troodon teeth. It proposes that the wear patterns of all Troodon teeth suggest a diet of soft foods - inconsistent with bone chewing, invertebrate exoskeletons, or tough plant items. This study hypothesizes a diet primarily consisting of meat.[14] A pellet possibly belonging to Troodon suggests it hunted early mammals such as Alphadon. [15]

In 2011, another derived troodontid, Linhevenator, was described from Inner Mongolia. It was noted by the authors as having relatively short and robust forelimbs, along with an enlarged second pedal ungual akin to that of the dromaeosaurids compared to more basal troodontids. It was proposed that derived troodontids had convergently evolved dromaeosaurid-style large second pedal unguals, likely as an adaptation relating to predation. The authors noted that it is plausible that this may be applicable to other derived troodontids, including Troodon, although this is currently uncertain due to a paucity of sufficient remains of the latter genus.[16]

Communal nesting

[edit]A 2023 study using presumed Troodon eggshells from the Oldman Formation used clumped isotope thermometry to determine their formation and development. The study found that in contrast to the accelerated mineralization of eggs in modern birds, Troodon and likely other non-avian maniraptorans had slowed egg calcification akin to other reptiles. This would indicate that, unlike birds, Troodon and other maniraptorans had two functional ovaries that would limit the number of eggs produced. Thus, the study concluded that the large clutches of fossilized eggs present in the formation, despite the limited egg production each individual had, would indicate that Troodon had communal nesting behavior, where eggs would be laid together at a single nest by multiple females, forming large clutches. This is a strategy also used by some modern birds, such as ostriches.[17][18]

Paleoecology

[edit]

The type specimen of Troodon formosus was found in the Judith River Formation of Montana. The rocks of the Judith River Formation are equivalent in age with the Oldman Formation of Alberta,[19] which has been dated to between 77.5 and 76.5 million years ago.[20]

In the past, remains have been attributed to the same genus as the Judith River Troodon from a wide variety of other geological formations. It is now recognized as unlikely that all of these fossils, which come from localities hundreds or thousands of miles apart, separated by millions of years of time, represent a single species or even a single genus of troodontid. Further study and more fossils are needed to determine how many species of Troodon existed. It is questionable that, after further study, any additional species can be referred to Troodon, in which case the genus would be considered a nomen dubium.[3]

Remains referred to Troodon are known from the Prince Creek Formation, a rock layer in Alaska that dates from the latest Campanian to Maastrichtian ages of the Late Cretaceous.[21] Based on the presence of gypsum and pyrite in the rocks, it suggests that the formation was bordered by a large body of water. It seems that, based on the presence of pollen fossils, the dominant plants were trees, shrubs, herbs, and flowering plants. The temperature ranged from possibly 2-12°C, which roughly correlates to 36-54°F, and based on Alaska's position in the late Cretaceous, the area faced 120 or so days of winter darkness.[22] This maniraptoran lived alongside many other reptiles, like the centrosaurine Pachyrhinosaurus perotorum, a species of the saurolophine hadrosaurid Edmontosaurus, the pachycephalosaurin Alaskacephale gangloffi, an unnamed azhdarchid pterosaur, and the tyrannosaurine Nanuqsaurus hoglundi. It also lived alongside the metatherian mammal Unnuakomys hutchisoni.[23] Based on the amount of teeth found, this troodontid was the most common theropod of the formation, making up 2/3 of all specimens, which is a stark contrast to more southern deposits in Montana, where troodontids only comprise 6% of all theropod remains.[24] This, along with evidence that Troodon was more abundant during cooler intervals, such as the early Maastrichtian, may indicate that Troodon favored cooler climates.[25]

Additional specimens currently referred to Troodon come from the upper Two Medicine Formation of Montana. Troodon-like teeth have been found in the lower Javelina Formation of Texas and the Naashoibito Member of the Ojo Alamo Formation in New Mexico.[26][27]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Holtz, Thomas R., Brinkman, Daniel L., Chandler, Christine L. (1998) Denticle Morphometrics and a Possibly Omnivorous Feeding Habit for the Theropod Dinosaur Troodon. Gaia number 15. December 1998. pp. 159-166.

- ^ Sauvage, H.-E. (1876). "Notes sur les reptiles fossiles". Bulletin de la Société géologique de France (in French) (3e série 4). Société géologique de France: 434–444.

- ^ a b c d e Lindsay E. Zanno, David J. Varricchio, Patrick M. O'Connor, Alan L. Titus and Michael J. Knell (2011). Lalueza-Fox, Carles (ed.). "A new troodontid theropod, Talos sampsoni gen. et sp. nov., from the Upper Cretaceous Western Interior Basin of North America". PLOS ONE. 6 (9): e24487. Bibcode:2011PLoSO...624487Z. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0024487. PMC 3176273. PMID 21949721.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Sternberg, C. (1945). "Pachycephalosauridae proposed for domeheaded dinosaurs, Stegoceras lambei n. sp., described". Journal of Paleontology. 19: 534–538.

- ^ a b van der Reest, A. J.; Currie, P. J. (2017). "Troodontids (Theropoda) from the Dinosaur Park Formation, Alberta, with a description of a unique new taxon: implications for deinonychosaur diversity in North America" (PDF). Canadian Journal of Earth Sciences. 54 (9): 919–935. Bibcode:2017CaJES..54..919V. doi:10.1139/cjes-2017-0031. hdl:1807/78296.

- ^ Russell, D. A.; Séguin, R. (1982). "Reconstruction of the small Cretaceous theropod Stenonychosaurus inequalis and a hypothetical dinosauroid". Syllogeus. 37: 1–43.

- ^ Currie, P. (1987). "Theropods of the Judith River Formation". Occasional Paper of the Tyrrell Museum of Palaeontology. 3: 52–60.

- ^ Paul, G.S. (1988). Predatory Dinosaurs of the World. New York: Simon and Schuster. pp. 398–399. ISBN 978-0-671-61946-6.

- ^ Currie, P. (2005). "Theropods, including birds." in Currie and Koppelhus (eds). Dinosaur Provincial Park, a spectacular ecosystem revealed, Part Two, Flora and Fauna from the park. Indiana University Press, Bloomington. Pp 367–397.

- ^ Evans, D. C.; Cullen, T.M.; Larson, D.W.; Rego, A. (2017). "A new species of troodontid theropod (Dinosauria: Maniraptora) from the Horseshoe Canyon Formation (Maastrichtian) of Alberta, Canada". Canadian Journal of Earth Sciences. 54 (8): 813–826. Bibcode:2017CaJES..54..813E. doi:10.1139/cjes-2017-0034.

- ^ Varricchio, D. J.; Kundrát, M.; Hogan, J. (2018). "An Intermediate Incubation Period and Primitive Brooding in a Theropod Dinosaur". Scientific Reports. 8 (1): 12454. Bibcode:2018NatSR...812454V. doi:10.1038/s41598-018-30085-6. PMC 6102251. PMID 30127534.

- ^ Sellés, A. G.; Vila, B.; Brusatte, S.L.; Currie, P.J.; Galobart, A. (2021). "A fast-growing basal troodontid (Dinosauria: Theropoda) from the latest Cretaceous of Europe". Scientific Reports. 11 (1): 4855. Bibcode:2021NatSR..11.4855S. doi:10.1038/s41598-021-83745-5. PMC 7921422. PMID 33649418.

- ^ a b Cullen, Thomas M.; Zanno, Lindsay; Larson, Derek W.; Todd, Erinn; Currie, Philip J.; Evans, David C. (2021-06-30). "Anatomical, morphometric, and stratigraphic analyses of theropod biodiversity in the Upper Cretaceous (Campanian) Dinosaur Park Formation1". Canadian Journal of Earth Sciences. 58 (9): 870–884. doi:10.1139/cjes-2020-0145.

- ^ Fiorillo, Anthony R. (2008) "On the Occurrence of Exceptionally Large Teeth of Troodon (Dinosauria: Saurischia) from the Late Cretaceous of Northern Alaska" Palaios volume 23 pp.322-328

- ^ Freimuth, William (2021). "Mammal-bearing gastric pellets potentially attributable to Troodon formosus at the Cretaceous Egg Mountain locality, Two Medicine Formation, Montana, USA". Palaeontology. 64 (5): 699–725. Bibcode:2021Palgy..64..699F. doi:10.1111/pala.12546. S2CID 237659529.

- ^ Xu X, Tan Q, Sullivan C, Han F, Xiao D (2011) A Short-Armed Troodontid Dinosaur from the Upper Cretaceous of Inner Mongolia and Its Implications for Troodontid Evolution. PLoS ONE 6(9): e22916. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0022916

- ^ Tagliavento, Mattia; Davies, Amelia J.; Bernecker, Miguel; Fiebig, Jens (April 3, 2023). "Evidence for heterothermic endothermy and reptile-like eggshell mineralization in Troodon, a non-avian maniraptoran theropod". PNAS. 120 (15): e2213987120. Bibcode:2023PNAS..12013987T. doi:10.1073/pnas.2213987120. PMC 10104568. PMID 37011196.

- ^ "Troodons laid eggs in communal nests just like modern ostriches". Popular Science. 2023-04-03. Retrieved 2023-04-05.

- ^ Eberth, David A. (1997). "Judith River Wedge". In Currie, Philip J.; Padian, Kevin (eds.). Encyclopedia of Dinosaurs. San Diego: Academic Press. pp. 199–204. ISBN 978-0-12-226810-6.

- ^ Arbour, V.M.; Burns, M. E.; Sissons, R. L. (2009). "A redescription of the ankylosaurid dinosaur Dyoplosaurus acutosquameus Parks, 1924 (Ornithischia: Ankylosauria) and a revision of the genus". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 29 (4): 1117–1135. Bibcode:2009JVPal..29.1117A. doi:10.1671/039.029.0405. S2CID 85665879.

- ^ Fiorillo, A.R.; Tykoski, R.S.; Currie, P.J.; Mccarthy, P.J.; Flaig, P. (2009). "Description of two partial Troodon braincases from the Prince Creek Formation (Upper Cretaceous), North Slope Alaska". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 29 (1): 178–187. doi:10.1080/02724634.2009.10010370. S2CID 197535475.

- ^ Druckenmiller, Patrick S.; Erickson, Gregory M.; Brinkman, Donald; Brown, Caleb M.; Eberle, Jaelyn J. (23 August 2021). "Nesting at extreme polar latitudes by non-avian dinosaurs". Current Biology. 31 (16): 3469–3478.e5. Bibcode:2021CBio...31E3469D. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2021.05.041. PMID 34171301. S2CID 235631483.

- ^ Eberle, Jaelyn J.; Clemens, William A.; McCarthy, Paul J.; Fiorillo, Anthony R.; Erickson, Gregory M.; Druckenmiller, Patrick S. (2019-04-26). "Northernmost record of the Metatheria: a new Late Cretaceous pediomyid from the North Slope of Alaska". Taylor & Francis. doi:10.6084/m9.figshare.8047169.v2.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ "The giant troodontid dinosaurs of Alaska". eartharchives.org.

- ^ Fiorillo, Anthony R.; Gangloff, Roland A. (2000). "Theropod teeth from the Prince Creek Formation (Cretaceous) of Northern Alaska, with speculations on Arctic dinosaur paleoecology". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 20 (4): 675–682. doi:10.1671/0272-4634(2000)020[0675:TTFTPC]2.0.CO;2. S2CID 130766946.

- ^ Langston, Standhardt and Stevens, (1989). "Fossil vertebrate collecting in the Big Bend - History and retrospective." in Vertebrate Paleontology, Biostratigraphy and Depositional Environments, Latest Cretaceous and Tertiary, Big Bend Area, Texas. Guidebook Field Trip Numbers 1 a, B, and 49th Annual Meeting of the Society of Vertebrate Paleontology, Austin, Texas, 29 October - 1 November 1989. 11-21.

- ^ Weil and Williamson, (2000). "Diverse Maastrichtian terrestrial vertebrate fauna of the Naashoibito Member, Kirtland Formation (San Juan Basin, New Mexico) confirms "Lancian" faunal heterogeneity in western North America." Geological Society of America Abstracts with Programs, 32: A-498.

- Russell, D. A. (1987). "Models and paintings of North American dinosaurs." In: Czerkas, S. J. & Olson, E. C. (eds) Dinosaurs Past and Present, Volume I. Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County/University of Washington Press (Seattle and Washington), pp. 114–131.