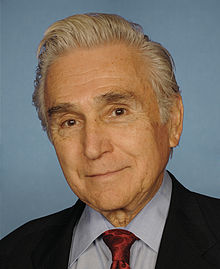

Maurice Hinchey

This article has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these messages)

|

Maurice Hinchey | |

|---|---|

| |

| Member of the U.S. House of Representatives from New York | |

| In office January 3, 1993 – January 3, 2013 | |

| Preceded by | Matthew F. McHugh |

| Succeeded by | Chris Gibson (redistricting) |

| Constituency | 26th district (1993–2003) 22nd district (2003–2013) |

| Member of the New York State Assembly from the 101st district | |

| In office January 1, 1975 – December 31, 1992 | |

| Preceded by | H. Clark Bell |

| Succeeded by | Kevin Cahill |

| Personal details | |

| Born | Maurice Dunlea Hinchey October 27, 1938 New York City, New York, U.S. |

| Died | November 22, 2017 (aged 79) Saugerties, New York, U.S. |

| Political party | Democratic |

| Spouse | Ilene Marder Hinchey |

| Children | 3, including Michelle |

| Alma mater | State University of New York at New Paltz |

| Military service | |

| Branch/service | United States Navy |

| Years of service | 1956–1959 |

Maurice Dunlea Hinchey (October 27, 1938 – November 22, 2017) was an American politician who served as a U.S. Representative from New York and was a member of the Democratic Party. He retired at the end of his term in January 2013 after 20 years in Congress.

He was born in New York City, and later moved to the Hudson Valley where he attended high school and college, Hinchey had previously represented part of the area in the New York State Assembly since 1975. As chair of that body's Environmental Conservation Committee, he took the lead in bringing environmental issues to the fore, particularly when he held hearings on the problems created by toxic waste disposal in the Love Canal neighborhood of Niagara Falls. In his later years in Congress, he opposed hydraulic fracturing to exploit the natural gas resources of the Marcellus Shale. Throughout his career, he was considered a political progressive for his liberal stands on other issues.

Early life, education and career

[edit]Hinchey was born to a working-class family on the Lower West Side of Manhattan, the son of Rose (Bonack) and Maurice D. Hinchey.[1] His mother was of Ukrainian descent and his father was the son of Irish immigrants.[2] He grew up in Saugerties, New York.[3][4]

After graduating from high school, Hinchey enlisted in the U.S. Navy and served in the Pacific on the destroyer USS Marshall. After being honorably discharged, he spent two years working as a laborer in a cement plant.[4] While in college, he earned his tuition working as a toll collector on the New York State Thruway.[5][6] He graduated from the State University of New York at New Paltz with a B.A. in 1968 and an M.A. in 1970.[7]

Hinchey first sought public office in 1972, with an unsuccessful race for the New York State Assembly. Ulster County was a Republican stronghold, but Hinchey ran successfully in 1974, becoming the first Democrat to represent Ulster County since 1912. Hinchey remained in the Assembly until 1992 and was a member of the 180th, 181st, 182nd, 183rd, 184th, 185th, 186th, 187th, 188th and 189th New York State Legislatures.[citation needed]

He was particularly noted for his work on protecting the natural environment. For 14 years, he chaired the Environmental Conservation Committee. Hinchey also served on the Ways and Means, Rules, Banks, Health, Higher Education, Labor, Energy and Agriculture committees.

During his chairmanship of the Committee on Environmental Conservation, the committee conducted a successful investigation into the causes of "Love Canal," the nation's first major toxic dump site. During his tenure, he aided in the passage of the country's first law concerning regulation of acid rain. His committee also gained public attention for its investigation of the infiltration of the waste removal industry by organized crime.[citation needed]

U.S. House of Representatives

[edit]Campaigns

[edit]In 1992, 28th District Congressman Matthew F. McHugh retired after 18 years in the House. Hinchey won the Democratic nomination for the district, which had been renumbered the 26th after New York lost three districts as a result of the 1990 census. He defeated Republican Robert Moppert, a county legislator in Broome County (which includes Binghamton) in the November general election by a 50% – 47% margin. In 1994, Hinchey faced Moppert again; in that year's Republican Revolution wave election, Hinchey won by only 1,200 votes.[citation needed]

Hinchey's district was significantly reconfigured when New York lost two congressional seats after the 2000 census. Hinchey was threatened with dismemberment of his district or with having to run against a popular and well-established Republican incumbent, either Ben Gilman or Sherwood Boehlert.[citation needed] In the intense political infighting over the redistricting, however, Hinchey emerged as one of the winners. To protect two younger Republican incumbents, the Republicans agreed to sacrifice the district of the 79-year-old Gilman, who chose to retire. In return, the Democrats accepted a district that threw together two of their incumbents, Louise Slaughter and John LaFalce, prompting the latter's retirement. Hinchey's district was renumbered the 22nd and wound a narrow, contorted path across eight counties in the southern part of the state, from the Hudson River through the Catskills and Binghamton to Ithaca, connecting the most politically liberal parts of the Southern Tier and Borscht Belt regions. This gerrymandered configuration is similar to the former New York's 26th congressional district.[8]

Hinchey ran in historically Republican areas throughout his career (his Assembly district was held by Republicans from 1915 until McHugh won it for the Democrats in 1975). He is best categorized as having been a progressive populist. For example, he was one of the first and most outspoken opponents of the 2003 war in Iraq, and one of only 11 co-sponsors of the Kucinich Resolution to impeach President Bush.[9] He bridged the ideological gap with a reputation for supporting many measures to improve integrity in government,[10][11][12][13] by popular (in New York) advocacy of strong environmental protection,[14][15] and by diligent constituent services. He sat on the Appropriations Committee, a post that helped him to deliver federal support on programs important to his district.[citation needed]

In 2010, Hinchey was elected to his tenth and final term, with a 52% to 48% margin over Republican George Phillips of Binghamton.[16]

Committee assignments

[edit]Caucus memberships

[edit]- Congressional Narcotics Abuse and Control Caucus[citation needed]

- Congressional Native American Caucus[citation needed]

- Congressional Progressive Caucus.[17]

- Education Caucus[citation needed]

- International Conservation Caucus[citation needed]

- Renewable Energy and Energy Efficiency Caucus[citation needed]

- Steel Caucus[citation needed]

- Congressional Arts Caucus[citation needed]

Hinchey was one of 31 members of the House who voted to uphold the objection to counting the 20 electoral votes from Ohio in the 2004 United States presidential election put forth by Ohio Rep. Tubbs Jones in order to encourage "a formal and legitimate debate about election irregularities".[18][19] Republican President George Bush had won the state by 118,457 votes after a recount.[20]

On June 18, 2008, he stated: "Should the people of the United States own refineries? Maybe so. Frankly, I think that's a good idea," but conceded it was unlikely the government would do so, and suggested putting national pressure on the oil companies.[21]

Energy

[edit]Hinchey was an original co-sponsor of the Small Business Clean Energy Financing Act. The act contributed about $630 million in loans to environmentally friendly energy companies in the years between 2006 and 2009.[22] Hinchey was a solar energy supporter; he helped organize the non-profit organization called The Solar Energy Consortium (TSEC). TSEC supports the growth of a solar energy industry in New York, creating green jobs in the Hudson Valley area. Hinchey supported the Home Star Energy Retrofit Act. The bill supports green energy by offering rebates to homeowners who improve their homes to conserve more energy.[23]

In 2010 midterm elections, Hinchey clashed with his opponent over shale gas drilling and hydraulic fracturing in upstate New York. Hinchey was against gas drilling in this area.[24] Also, the Obama administration refused a request by Hinchey to slow down drilling in New York and Pennsylvania.[25] Along with Rep. Diana DeGette (D-Colo.) and Sen. Bob Casey (D-Pa.), Hinchey introduced legislation called the "FRAC Act" which proposes lifting fracturing exemptions and forcing public disclosure of chemicals used.[25]

Environment

[edit]Hinchey supported the Clean Air Act and did not approve of the Bush administration's decision to roll back the New Source Review (NSR) component of the Act, fearing it would result in increased acid rain and more pollution of the lakes of the area.[26]

Hinchey appeared in the 2010 documentary Gasland, discussing the FRAC Act, which he co-sponsored.[citation needed]

Medical marijuana

[edit]Hinchey introduced the Hinchey–Rohrabacher amendment in 2001, to prohibit the Justice Department from taking actions to interfere with the implementation of state medical cannabis laws.[27] The amendment failed 152–273 upon its initial vote in 2003 and was defeated several more times in subsequent years up until Hinchey's 2012 retirement. In 2014, however, the amendment passed the House as the Rohrabacher–Farr amendment and was signed into law, providing supporters of medical cannabis with a key victory at the federal level.[28]

In 2009, the U.S. House Committee on Appropriations approved adding a provision authored by Hinchey to the committee report on the fiscal 2010 Justice Department appropriations bill, requesting "clarification of the Department's policy regarding enforcement of federal laws and use of federal resources against individuals involved in medical marijuana activities."[29]

Abortion

[edit]Hinchey supported a pro-choice position on abortion issues.[26] He was a cosponsor of the Freedom of Choice Act and the Freedom of Access to Clinic Entrances Act, which seeks federal protection of free access to women's clinics and he fought Republican attempts to reduce abortion rights.[26] Hinchey was also an advocate for family planning programs, including the Title X program.[26]

However, Hinchey opposed late-term abortions except where necessary to protect the health of the mother.[26]

Other memberships

[edit]- Board of Visitors for the U.S. Military Academy at West Point[citation needed]

- Member, National Conference of State Legislators[citation needed]

- National Guard and Reserve Components Congressional Members Organization[citation needed]

- New York State Council of Governments[citation needed]

- Member, board of directors, Ulster-Greene ARC[citation needed]

- Member, board of directors, WAMU Public Radio[citation needed]

Member, Eastern Regional Conference of the Council of State Governments and chair of its Environment Committee

Honors

[edit]Hinchey was made an Officer of the Order of Orange-Nassau on September 4, 2009, by the Ambassador of the Netherlands in capacity of Queen Beatrix. He was awarded the Dutch royal order for his work to commemorate the quadricentennial anniversary of Henry Hudson's exploration and discovery of the river in New York and for Hinchey's efforts to strengthen the U.S.-Netherlands relationship.[30]

Later votes

[edit]Representative Hinchey voted yes on H.R. 2433 Veterans Opportunity to Work Act of 2011.[31] This law amended title 38, United States Code, to make certain improvements in the laws relating to the employment and training of veterans, and for other purposes.[32]

Hinchey, in August 2010, voted yes on the "Offshore Drilling and Other Energy Laws Amendments."[33] This regulates or controls the use of oil and natural gas.[33] It also increases safety on blowout preventers on oil wells, as well as upping the penalty for leaking or spilling of oil or "other hazardous substances" into the Gulf of Mexico. He also voted to repeal Don't Ask, Don't Tell in March 2010. This makes it illegal to dismiss someone from the army for being homosexual, having engaged in or suspected of engaging in "homosexual acts."[citation needed]

Another bill Hinchey voted yes on, the Aid to States for Medicaid, Teacher Employment and Other purposes, passed in the House in August 2010. This budgets $10 billion to the Education Jobs Fund to be given to the states for teacher hiring and training. It also increases Federal Medical Assistance Percentages (FMAP) to states in need and lengthens the period for states to increase their FMAP.[33]

In November 2011, he voted to reaffirm "In God We Trust" as the national motto and "encourag[e] the public display of the national motto in all public buildings, public schools, and other government institutions."[34]

Speeches and public statements

[edit]In a letter sent on November 10, 2010, to Jeffrey Zients, the acting director of the Office of Management and Budget, Hinchey promoted the support of Job Corps. This program helps high-school dropouts find careers and receive their high school diplomas or GED's. He asked Zients for increased federal funding for this recovery program in the 2012 budget.[33]

On October 18, 2010, Hinchey held a Medicare forum to reassure seniors about provisions in the health care bill that would or would not change parts of Social Security and Medicare. He stated that the health care reform bill would increase the efficiency of Medicare; the Act would not cut into Medicare or social security funding.[citation needed]

Hinchey wrote a letter to President Barack Obama in October 2010 regarding Social Security. In the letter, he described to Obama how he believes social security is important and urged the President to increase its budget in the upcoming year.[33]

Arctic offshore drilling

[edit]In May 2010, Hinchey, along with two other Progressive democrats, Lois Capps and Jay Inslee, began a petition to ask Obama to delay Shell from beginning exploratory drilling near Alaska. They wanted to understand the causes of the Gulf oil spills before Shell went ahead with Offshore drilling. Hinchey and the others were worried about the environmental effects if an accident were to occur; in the Arctic waters, a spill would not be contained as in the Gulf spill. Another priority was assuring native communities would not be harmed; since they often depend on fish and marine life to sustain them, their resources would be depleted if a spill happened.[35]

Bush administration's warrantless surveillance program

[edit]After the New York Times first disclosed the existence of the Bush administration's warrantless surveillance program in late 2005, Hinchey was among the earliest members of Congress to criticize the program. Not long after, Hinchey—along with three other House Democrats—John Lewis of Georgia, Henry Waxman of California, and Lynn Woolsey of California—wrote the Justice Department, requesting an investigation to determine whether Bush administration violated any laws in authorizing and carrying out the program.[5] As a result, the Justice Department's Office of Professional Responsibility (OPR) commenced an investigation.[5][36] It was later disclosed the OPR investigation was closed when President Bush refused to allow the Justice Department attorneys who were to conduct the investigation to have the security clearances to conduct the inquiry.[36] After a public outcry, President Bush capitulated and allowed the investigators to have their security clearances so they could conduct the inquiry.[37]

1994 gun incident

[edit]In December 1994, Hinchey was issued a summons after X-ray machines at Washington National Airport found a loaded .32-caliber handgun in his carry-on luggage before he boarded a flight. Hinchey claims to have forgotten the handgun was in his luggage. He pleaded no contest and was fined.[38]

Retirement

[edit]In January 2012, Hinchey held a news conference at Senate House in Kingston, where he had announced his first run for Congress two decades earlier, to announce his retirement. "It's time for someone else", he told assembled reporters. His illness and age had been factors.[39]

He denied his decision to step down had anything to do with the state's pending redistricting but said he wanted to make his intentions clear before the process was completed. His departure was seen as making it easier for the state's Democratic Party to decide which member of its congressional delegation would have to give up their district since New York had to eliminate two of its seats that year.[40] Hinchey's seat was one of two, the other being that of newly elected Republican Bob Turner, eliminated in redistricting.

Personal life

[edit]On April 22, 2011, Hinchey's office announced he was being treated for a curable form of colon cancer. A statement released by his office said Hinchey would have surgery at the Albany Medical Center, receive treatment at the Ulster Radiation Oncology Center in Kingston, New York, and also undergo chemotherapy.[41][42][43] The statement said he would continue to work during his treatment. [41]

Hinchey had three children, one of whom, Michelle, went on to become a New York State Senator. He and his wife, Ilene Marder Hinchey, resided together in Saugerties, New York.[6]

Death

[edit]Shortly after being treated for colon cancer, Hinchey began experiencing symptoms of frontotemporal dementia, a diagnosis that his family did not make public until 2017.[44] Hinchey died from the disease at his home in Saugerties on November 22, 2017, at age 79.[3][45] In December 2017, the Chicago City Council passed a resolution honoring Hinchey.[46]

On July 26, 2018, President Donald Trump signed a bill renaming the Saugerties Post Office after Hinchey.[47]

References

[edit]- ^ Hinchey ancestry.com [dead link][user-generated source]

- ^ Gref, Barbara (October 16, 2000). "Hinchey got to Washington via the Thruway". Times Herald-Record. Retrieved April 23, 2024.

- ^ a b Stevens, Matt (November 23, 2017). "Maurice D. Hinchey, Congressman and Environmental Advocate, Dies at 79". The New York Times. Retrieved January 16, 2020.

- ^ a b "About Maurice Hinchey". United States House of Representatives. Archived from the original on May 4, 2011. Retrieved April 26, 2011.

- ^ a b c "Writing Letters – July 19, 2006 – The New York Sun". Nysun.com. Retrieved November 21, 2011.

- ^ a b "About Maurice Hinchey". Hinchey.house.gov. Archived from the original on February 8, 2012. Retrieved November 21, 2011.

- ^ "Bioguide Search". bioguide.congress.gov. Retrieved March 20, 2023.

- ^ "New York Redistricting 2000". Voting and Democracy Research Center. Retrieved December 2, 2010.

- ^ "H. Res. 1258 [110th]: Impeaching George W. Bush, President of the United States, of high crimes and misdemeanors". GovTrack.us. Retrieved August 23, 2010.

- ^ "Maurice Hinchey". Historycommons.org. Retrieved August 23, 2010.

- ^ "Maurice D. Hinchey, Currently Elected New York Rep. In Congress District 22". Vote-usa.org. Retrieved August 23, 2010.

- ^ "Integrity in Science Watch ~ Newsroom ~ News from CSPI". Cspinet.org. May 15, 2006. Retrieved August 23, 2010.

- ^ "Cong. Hinchey calls for ouster of FDA Counsel – Sen. Bingaman & Reed tell FDA: disclose all trial info". Ahrp.org. Retrieved August 23, 2010.

- ^ "Hinchey, New York House Colleagues Introduce Bill To Require Independent Safety Assessment Of Indian Point" (PDF). www.riverkeeper.org. Archived from the original (PDF) on January 15, 2007.

- ^ "Archived copy" (PDF). www.nylcv.org. Archived from the original (PDF) on February 3, 2009. Retrieved January 17, 2022.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ Wind, Kyle (November 3, 2010). "22nd CD: Hinchey elected to 10th term (updated 6:33 a.m.)". Daily Freeman. Retrieved November 3, 2010.

- ^ "Congressional Progressive Caucus". Archived from the original on December 12, 2008. Retrieved December 15, 2008.

- ^ "Congresswoman Tubbs Jones' (Democrat Ohio) 6 January 2005 Objection to the Certification of Ohio Electoral Votes". Thegreenpapers.com. Retrieved August 23, 2010.

- ^ "Final vote results for roll call 7". clerk.house.gov. Retrieved December 18, 2023.

- ^ Salvato, Albert (December 29, 2004). "Ohio Recount Gives a Smaller Margin to Bush". The New York Times.

- ^ "Rep. Hinchey Steps Off Idea of Oil Refinery Nationalization". Fox News.com. June 19, 2008. Retrieved December 2, 2010.

- ^ "The Voter's Self Defense System".

- ^ "Energy Independence". Archived from the original on November 23, 2010. Retrieved November 24, 2010., Energy Reform.

- ^ Greenwire, MIKE SORAGHAN of. "Fracking Pumps Up Pressure in Upstate N.Y. Congressional Race". archive.nytimes.com. Retrieved October 16, 2022.

- ^ a b Greenwire, MIKE SORAGHAN of. "Obama's Enthusiasm for Gas Drilling Raises Eyebrows". archive.nytimes.com. Retrieved October 16, 2022.

- ^ a b c d e "The Voter's Self Defense System". Vote Smart. Retrieved October 16, 2022.

- ^ "Hinchey-Rohrabacher amendment Archives". The National Cannabis Industry Association. Retrieved March 20, 2023.

- ^ Angell, Tom (November 24, 2017). "Federal Medical Marijuana Amendment Author Dies At 79". Marijuana Moment. Retrieved November 24, 2017.

- ^ Hinchey, Maurice (June 9, 2009). "House panel approves Hinchey provision requesting clarification from Obama administration on medical marijuana policy (press release)". house.gov/hinchey. Archived from the original on June 28, 2009. Retrieved June 16, 2009.

U.S. House Committee on Appropriations (June 12, 2009). "Report 111-149 on H.R. 2847 Commerce, Justice, and Related Agencies Appropriations Bill, 2010" (PDF). U.S. Government Printing Office. pp. 66–7. Retrieved June 16, 2009. - ^ Queen of the Netherlands honors Hinchey Archived September 7, 2009, at the Wayback Machine – Announcement on the official U.S. government site Hinchey

- ^ "H.R. 2433 (112th): Veterans Opportunity to Work Act of 2011 -- House Vote #785 -- Oct 12, 2011". GovTrack.us. October 12, 2011. Retrieved December 18, 2023.

- ^ "H.R. 2433: Veterans Opportunity to Work Act of 2011". GovTrack.us. Retrieved November 21, 2011.

- ^ a b c d e "Project Vote Smart". Vote-smart.org. Archived from the original on November 17, 2011. Retrieved November 21, 2011.

- ^ "H. Con. Res. 13: Reaffirming "In God We Trust"". GovTrack.us. Retrieved November 22, 2011.

- ^ Geman, Ben (May 20, 2010). "House Dems Pressure White House to Block Arctic Offshore Drilling". Thehill.com. Archived from the original on June 29, 2011. Retrieved November 21, 2011.

- ^ a b "National Journal Magazine - Top News". news.nationaljournal.com. Archived from the original on November 15, 2010.

- ^ "Murray Waas: Justice Department Reopens Probe Into Warrantless Domestic Spying". Huffingtonpost.com. December 7, 2010. Retrieved November 21, 2011.

- ^ Solomon, John (December 1, 1994). "New York Congressman Issued Summons for Loaded Gun at Airport". Associated Press. Retrieved November 29, 2017.

- ^ "Hinchey makes retirement from Congress official: 'It's time for someone else...'". Times-Herald Record. January 19, 2012. Retrieved January 19, 2012.

- ^ Hernandez, Raymond (January 19, 2012). "Hudson Valley Democrat Won't Seek 11th Term in Congress". The New York Times. Retrieved January 19, 2012.

- ^ a b "Rep. Maurice Hinchey treated for colon cancer". USA Today. April 22, 2011.

- ^ Meghan E. Murphy (April 23, 2011). "Hinchey diagnosed with treatable colon cancer". recordonline.com. Archived from the original on October 8, 2012. Retrieved November 21, 2011.

- ^ "Rep. Hinchey being treated for cancer – Jennifer Epstein". Politico.Com. April 22, 2011. Retrieved November 21, 2011.

- ^ "Maurice Hinchey, former congressman, has terminal neurological disorder, family announces". The Daily Freeman. Kingston, New York. June 27, 2017. Retrieved June 27, 2017.

- ^ "Former U.S. Congressman Maurice Hinchey dies". WBNG. November 22, 2017. Archived from the original on November 25, 2017. Retrieved November 22, 2017.

- ^ Burke, Ed (December 13, 2017). "R2017-1164 - Tribute to late Maurice Hinchey". Chicago City Council. Retrieved June 11, 2018.

- ^ "Bill to name Saugerties Post Office for late Rep. Hinchey signed by Trump". The Daily Freeman. Saugerties, New York. July 26, 2018. Retrieved July 26, 2018.

External links

[edit]- United States Congress. "Maurice Hinchey (id: H000627)". Biographical Directory of the United States Congress.

- Appearances on C-SPAN

- 1938 births

- 2017 deaths

- 20th-century American politicians

- 21st-century American politicians

- American people of Irish descent

- American politicians of Ukrainian descent

- Deaths from frontotemporal dementia

- Democratic Party members of the United States House of Representatives from New York (state)

- Democratic Party members of the New York State Assembly

- Deaths from dementia in New York (state)

- Officers of the Order of Orange-Nassau

- People from Hurley, New York

- People from Saugerties, New York

- People from the Catskills

- People from Tribeca

- State University of New York at New Paltz alumni

- United States Navy sailors

- Love Canal