Naihanchi

| 内歩進 (内畔戦, 内範置, 鉄騎) | |

| Japanese: | naihanchi (ナイハンチ), naihanchin (ナイハンチン), naihanchen (ナイハンチェン) |

| Ryukyuan: | naifanchi (ナイファンチ), naifanchin (ナイファンチン), naifanchen (ナイファンチェン) |

| Shotokan: | tekki (鉄騎), old:kiba-dachi (騎馬立ち) |

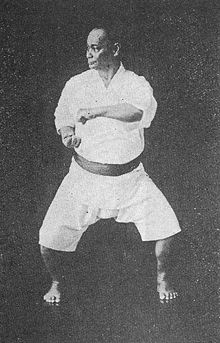

Naihanchi (ナイハンチ) (or Naifanchi (ナイファンチ), Tekki (鉄騎)) is a karate kata, performed in straddle stance (naihanchi-dachi (ナイハンチ立ち) / kiba-dachi (騎馬立ち)). It translates to 'internal divided conflict'. The form makes use of in-fighting techniques (i.e. tai sabaki (whole body movement)) and grappling. In Shorin-Ryu and Matsubayashi-ryū Naihanchi Shodan is the first ni kyu (brown belt kata) although it is taught to yon kyu (green belts) occasionally before evaluations for the ni kyu rank. It is also the first Shorin-ryu and Shindo jinen-ryu kata to start with a technique to the right instead of the left. There are three modern kata derived from this (Shodan, Nidan and Sandan). Some researchers believe Nidan and Sandan were created by Anko Itosu, but others believe that it was originally one kata broken into three separate parts. The fact that only Naihanchi/Tekki Shodan has a formal opening suggests the kata was split.

Whilst the kata is linear, moving side to side, the techniques can be applied against attackers at any angle. The side to side movements in a low stance build up the necessary balance and strength for fast footwork and body shifting. The kata are intricate strategies of attacking and defensive movement, done in either naihanchi (or naifanchi) dachi, a shoulder-width stance with the toes angled inwards, or the kiba dachi, for the purpose of conditioning the legs to develop explosive power. If one rotates one's torso a few degrees to one side or the other while performing Naihanchi/Tekki, the result is the Hachi-monji, or figure eight stance. Some researchers[1] believe the form is a non-ballistic two-man grappling exercise.

History

[edit]In his 1922 book titled To-te: Ryūkyū Kenpō / 唐手 琉球拳法 Gichin Funakoshi called this series of forms "Naihanchi (ナイハンチ)" and attributes the form to what he calls the "Shōrei-Ryu/昭霊流."[2] Similarly, Motobu Chōki spells the name of this form "Naihanchi/ナイハンチ" in his 1926 Okinawa Kenpō To-te Jutsu/沖縄拳法唐手術.[3] By 1936, in his Karate-do Kyohan/空手道教範 Funakoshi had started referring to this form as “Kibadachi (騎馬立/キバ ダチ)” or “Cavalry Horse Stance,” while still referencing the original “Naihanchi / ナイハンチ” name.[4] In the 1973 "Karate-do Kyohan The Master Text", a translation of the 1956 second edition of the Kyohan book, there is no longer any mention of Naihanchi and the book claims the form, which it calls "Tekki" is named in reference to "the distinctive feature of these kata, their horse-riding (kiba-dachi) stance."[5] Other than the "Shorei-Ryu" reference, none of these books attribute the form to any particular source or practitioner.

Itosu is reported to have learned the kata from Sokon Matsumura, who learned it from a Chinese man living in Tomari. Itosu is thought to have changed the original kata. The form is so important to old style karate that Kentsu Yabu (a student of Itosu) often told his students 'Karate begins and ends with Naihanchi' and admonished his students must practice the kata 10,000 times to make it their own. Before Itosu created the Pinan (Heian) kata, Naihanchi would traditionally be taught first in Tomari-te and Shuri-te schools, which indicates its importance. Gichin Funakoshi learned the kata from Anko Asato. Funakoshi renamed the kata Tekki (Iron Horse) in reference to his old teacher, Itosu, and the form's power.[citation needed]

The oldest known reference to Naihanchi are in the books of Motobu Choki. He states the kata was imported from China, but is no longer practiced there. Motobu learned the kata from Sokon Matsumura, Sakuma Pechin, Anko Itosu and Kosaku Matsumora. Motobu taught his own interpretation of Naihanchi, which included te (Okinawan form of martial arts which predates karate) like grappling and throwing techniques.

In the earlier days of karate training, it was common practice for a student to spend two to three years doing nothing but Naihanchi/Tekki, under the strict observation of their teacher. Motobu Choki, famous for his youthful brawling at tsuji (red-light district), credited the kata with containing all that one needs to know to become a proficient fighter.

The Tekki series of kata were renamed by Funakoshi from the Naihanchi kata, which were derived from an older, original kata, Nifanchin.[6] Nifanchin was brought to Okinawa via Fuzhou, China, at some point in the long history of trade between the two kingdoms. It was broken into three distinct segments, possibly by Anko Itosu, Tokumine Pechin, or Motobu Choki. The kata are performed entirely in Kiba dachi ("Horse stance"). The name Tekki itself (and Nifanchin) translates to "Iron Horse." Tekki Shodan (鉄騎初段), literally meaning "Iron Horse Riding, First Level", is the first of the series, followed by Tekki nidan and Tekki sandan.

In the 1960s a kung fu practitioner, Daichi Kaneko, studied a form of Taiwanese white crane kung-fu, known as Dan Qiu Ban Bai He Quan (Half Hillock, Half White Crane Boxing). Kaneko, an acupuncturist who lived in Yonabaru, Okinawa, taught a form called Neixi (inside knee) in Mandarin. This form includes the same sweeping action found in the nami-gaeshi (returning wave) technique of Naihanchi. Neixi is pronounced Nohanchi in Fuzhou dialect, which could indicate Neixi is the forerunner to Naihanchi. Neixi is also the shortened form of the mandarin 内 Nei (internal/inside) 方 Fang (place/location) 膝(厀) Xi (knee). This is closer to the original Nifanchin pronunciation. Taking this one step further, in Classical Chinese, Nei could have had a double meaning. One straightforward reference to the inside knee and one indirect reference to soft styles of traditional Chinese martial arts such as tai chi (also see neigong).[citation needed]

Embusen 演武線

[edit]The embusen is a straight line, running horizontally to the left and right of the dojo.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Johnson, Nathan (2000). Barefoot Zen: The Shaolin Roots of Kung Fu and Karate. York Beach: Weiser. ISBN 9781609253967.

- ^ Funakoshi, Gichin (1920). "To-te Jutsu". National Diet Library. p. 74. Retrieved 4 March 2014.

- ^ Motobu, Chōki (1920). "Okinawa Kenpo Karate Jutsu". National Diet Library. p. 7. Retrieved 4 March 2014.

- ^ Funakoshi, Gichin (1936). "Karate-do Kyohan" (PDF). University of Hawaii Karate Museum. p. 73. Archived from the original (PDF) on 24 September 2015. Retrieved 4 March 2014.

- ^ Karate-Do Kyohan, ISBN 1568364822 p 36.

- ^ Advanced Shotokan Karate Kata, John van Weenen, ISBN 0-9517660-1-5

External links

[edit]- Naihanchi on fightingarts.com

- Naihanchi Shodan and Nidan

- http://wadokaionline.com/article-on-naihanchi-kata.html Article on Wadoryu Naihanchi

Further reading

[edit]- Joe Swift - Roots of Shotokan: Funakoshi's Original 15 Kata; Part 2 - Pinan, Naihanchi, Kushanku & Passai Kata [1]

- Nathan Johnson – Barefoot Zen: The Shaolin Roots of Kung Fu and Karate, Weiser, York Beach, 2000.

- Shoshin Nagamine – The Essence of Okinawan Karate-Do, Tuttle, Boston, 1998.

- Mark Bishop – Okinawan Karate, Tuttle, Boston, 1999.

- Shoshin Nagamine – Tales of Okinawa's Great Masters, Tuttle, Boston, 1999.

- Bruce D. Clayton - Shotokan's Secret: The Hidden Truth Behind Karate's Fighting Origins, Black Belt Communications, 2004.